Gustave Flaubert (1821.1880)

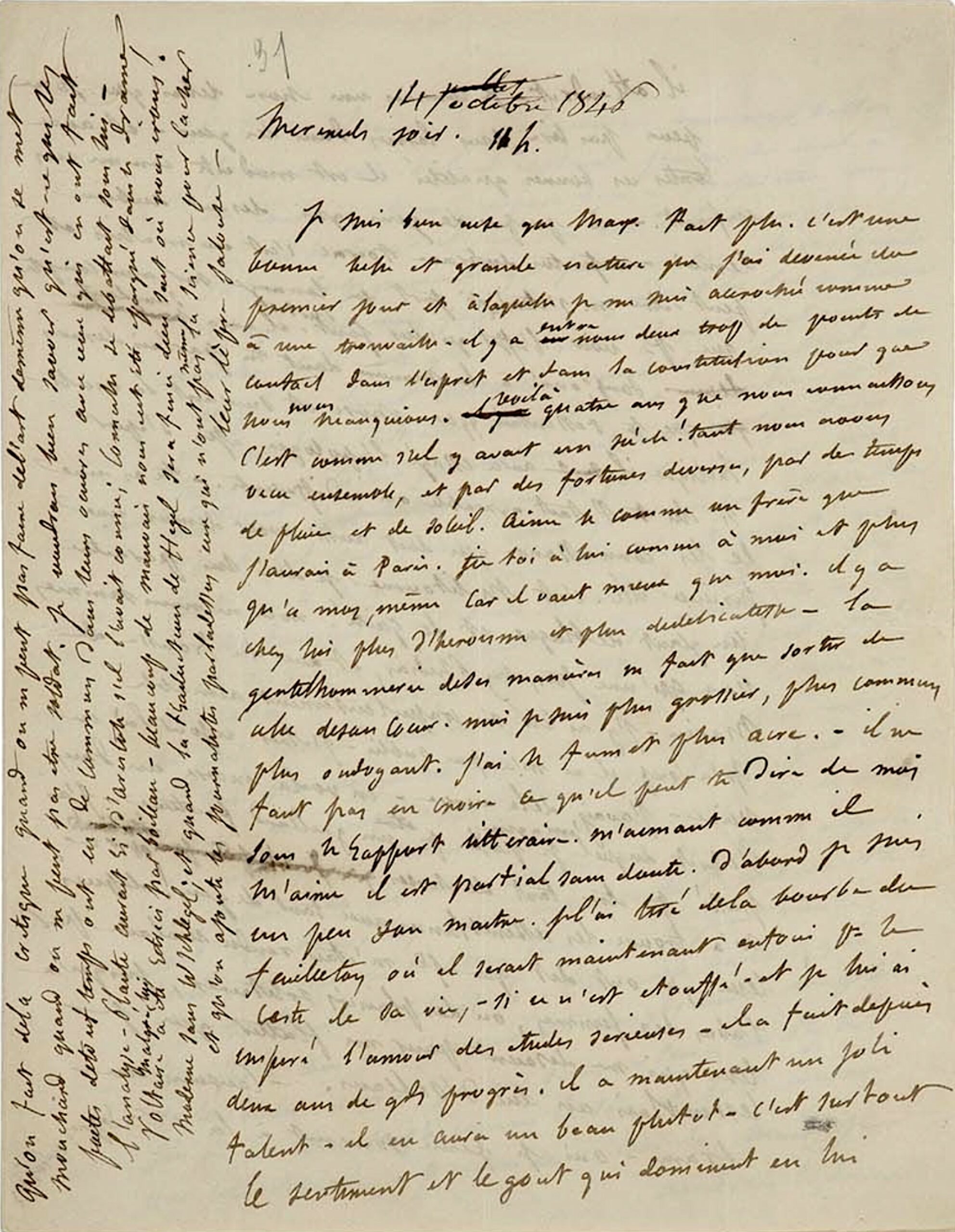

Autographed letter to Louise Colet.

Four pages in quarto. [Croisset. October 14, 1846].

Flaubert, Correspondence I , Pléiade, pp. 388-391.

"Since my father and sister died, I have no ambition left. I don't even know if a single line of my name will ever be printed."

Superb letter: the friend "Max" (Du Camp), the danger of self-serving compliments, the drama of Louise Colet in preparation, the lack of literary ambition, work, the mediocrity of criticism or the "jealous leprosy" of journalists…

____________________________________________

Flaubert's tumultuous relationship with Louise Colet (1810-1876) is one of the most celebrated in literary history, giving rise to a justly famous correspondence. It was in Paris, in the studio of the sculptor Pradier, that the novelist met Louise, née Révoil, in June 1846. She was more than ten years his senior. Married in 1834 to the flautist Hippolyte Colet, she had previously had several affairs, notably with the philosopher Victor Cousin, who was, or believed himself to be, the father of her daughter Henriette and who devoted himself to her service for sixteen years. A writer herself, she composed primarily poems, collections of which were awarded prizes by the French Academy on several occasions.

Their affair began on July 29, 1846, five and a half months before this letter. Back in Croisset, Flaubert wrote to her often and at length. They sometimes met in Mantes or Paris, but less frequently than she would have liked. A lover and confidante with whom he exchanged ideas and discussed literature, she inspired the bear of Croisset to write some of his most beautiful letters, written "in fits and starts," as in this one.

Louise Colet had just met Maxime Du Camp (a meeting which she would recount in 1856, romanticizing it, in Une histoire de soldat ): Flaubert told her how much this chosen brother was a reliable friend.

« I'm so glad you liked Max. He's a good, beautiful, and generous soul, a quality I sensed from the very first day and to which I've clung as to a precious find. There are too many points of contact between us, in mind and constitution, for us to ever miss each other . We've known each other for four years now. It feels like a century! We've lived so much together, through varying fortunes, through rain and sunshine. Love him like a brother I would have in Paris. Trust him as you would me, and more than myself, for he is better than I am. He possesses more heroism and more refinement—the gentlemanly manner of his actions simply stems from the gentleness of his heart. I am coarser, more common, more fickle. I have a more acrid scent —don't believe what he might tell you about me from a literary standpoint. Loving me as he does, he is undoubtedly biased. First of all, I am somewhat his mentor. I pulled him out of the mire of the soap opera where he would now be buried for the rest of his life—if not suffocated—and I instilled in him a love of serious study . He has made great progress in the last two years. He now has a fine talent—he will have a fine one, rather—it is above all feeling and taste that dominate him. He is endearing; I know nothing about him that I cannot read without tears in my eyes. And with all these good qualities, he is as modest as a child. »

Aware of the maneuvers in the literary world, the novelist warns Louise Colet about the self-serving compliments of her relatives and their manipulations.

“ Speaking of people who speak well of me, beware of good old Toirac; he’s a sly fellow, and perhaps he only heaps praise on me to see what effect it has on you. He probably suspected from the way you spoke of me that you felt something, and, following the old tactic, he tried to flatter you to see if it pleased you or left you indifferent. – You have an acquaintance who must also have a very high opinion of me. It’s Malitourne. I must seem to him like a giant of jokes and gaiety. We’ve only met once, at Phidias’s, and with Marin’s Redhead. I was so wickedly charming there that he certainly hasn’t forgotten me. I was on a roll that day; I was full of energy.” Here's another one in whose mind, I imagine, I'm considered a mischievous fellow. I've been considered so many things, and people have found similarities between me and so many others! From those who said I made myself ill through the abuse of women, or solitary pleasures, to those who flattered me that I resembled the Duke of Orléans .

Then Gustave Flaubert mentions the play his mistress is working on: begun in 1845 under the title Madeleine, the play was not finished until 1847, but rejected by the Comédie-Française in 1848. (It was published in 1850 under the new title Une famille en 1793. )

« Let's talk about the drama. Yes, I often think about the first performance, it torments me! – Oh, how my heart will pound! I know myself; if it's applauded, I'll have trouble containing myself. I'm preparing myself well for misfortune, but not for happiness , and it will be happiness if you triumph! Oh! Those stamping feet I dreamed of in school, my elbow resting on my desk, gazing at the smoky lamp in our study! That noisy glory, the mere thought of which made me tremble, I will have all of that, I, and in you, that is to say, in the sensitive part of myself. In the evening, I will kiss that noble breast whose feeling will have stirred the crowd like a great wind on the water. »

Admitting his lack of ambition, not without a certain bad faith, Flaubert offers valuable advice on writing and style:

“ Since my father and sister died, I have no more ambition. They took my vanity with them in their shroud, and they still keep it. I don't even know if a single line of my work will ever be printed. I'm not like the fox who finds the fruit too green to eat. But I 'm no longer hungry. Success doesn't tempt me. What tempts me is the success I can give myself, my own approval, and perhaps I'll end up doing without it, just as I should have done without the approval of others. So it's to you, upon you, that I turn all this. Work, meditate, meditate above all, condense your thoughts; you know that beautiful fragments amount to nothing. Unity, unity, that's all there is to it. The whole, that's what everyone today lacks, the great and the small. A thousand beautiful places, not a single work. Tighten your style, make it a fabric as supple as silk and as strong as chainmail.” "Excuse the advice, but I want to give you everything I desire for myself. "

He has to go to Rouen to spend the winter with his mother.

« It's still raining; the weather is dreary, and what about me? I'm working quite a bit these days. I have several things I want to finish that bore me, but I keep going nonetheless, hoping to get something out of them later —next spring, though, I'll start writing again. But I keep putting it off. A subject to tackle is, for me, like a woman one is in love with—when she's about to give in to you, you tremble and you're afraid; it's a voluptuous dread. You don't dare touch her desire. »

He finds in Chateaubriand an illustration of his feelings:

« Martyrs tonight . What a beautiful thing! What poetry! But if I had been Eudore and you had been the druidess, I would have given in more quickly. I can't help but feel a sense of bourgeois indignation when I see men resisting women in books. We always think it's the author talking about himself, and we find it impertinent because it might not be true after all. »

Then Flaubert puts an end to the rumors and the criticism, which is not only mediocre but dangerous for writers who try their hand at it:

« You're talking to me about Albert Aubert, and Mr. Gaschon of Molesnes. I despise all these clowns – What's the point of worrying about these blackbirds chirping? It's a waste of time to read reviews – I'm confident I can argue in a thesis that there hasn't been a single good one since they started – that they only serve to annoy authors and stupefy the public – and finally, that one becomes a critic when one cannot create art, just as one becomes an informer when one cannot be a soldier.

I would very much like to know what poets throughout history have had in common in their works with those who have analyzed them – Plautus would have laughed at Aristotle had he known him, Corneille struggled under his influence – Voltaire, despite himself, was diminished by Boileau – much harm would have been spared us in modern drama without W. Schlegel; and when the translation of Hegel is finished, God knows where we will end up! And then there are the journalists on top of that, they who don't even have the knowledge to hide their jealous leprosy .

He concluded in a comical way, as if he were regaining his composure after an outburst of fury:

“ I let my hatred of criticism and critics get the better of me, so much so that these wretches took up all the space I needed to kiss you – but despite themselves, that’s what I’m doing. So, with their permission, a thousand big kisses on your beautiful brow and on your sweet eyes and… ”

After an initial breakup in 1848, Flaubert resumed his relationship upon his return from the trip to the Orient – until 1855. “ You are the only woman I have ever loved and had ,” the sentimental misogynist confessed to her.

____________________________________________

Flaubert, Correspondence I, Pléiade, pp. 388-391: the date at the top was indicated by Louise Colet who first wrote "July" before changing her mind to write "October", probably by a kind of automatism.

Provenance: J. Lambert collection.