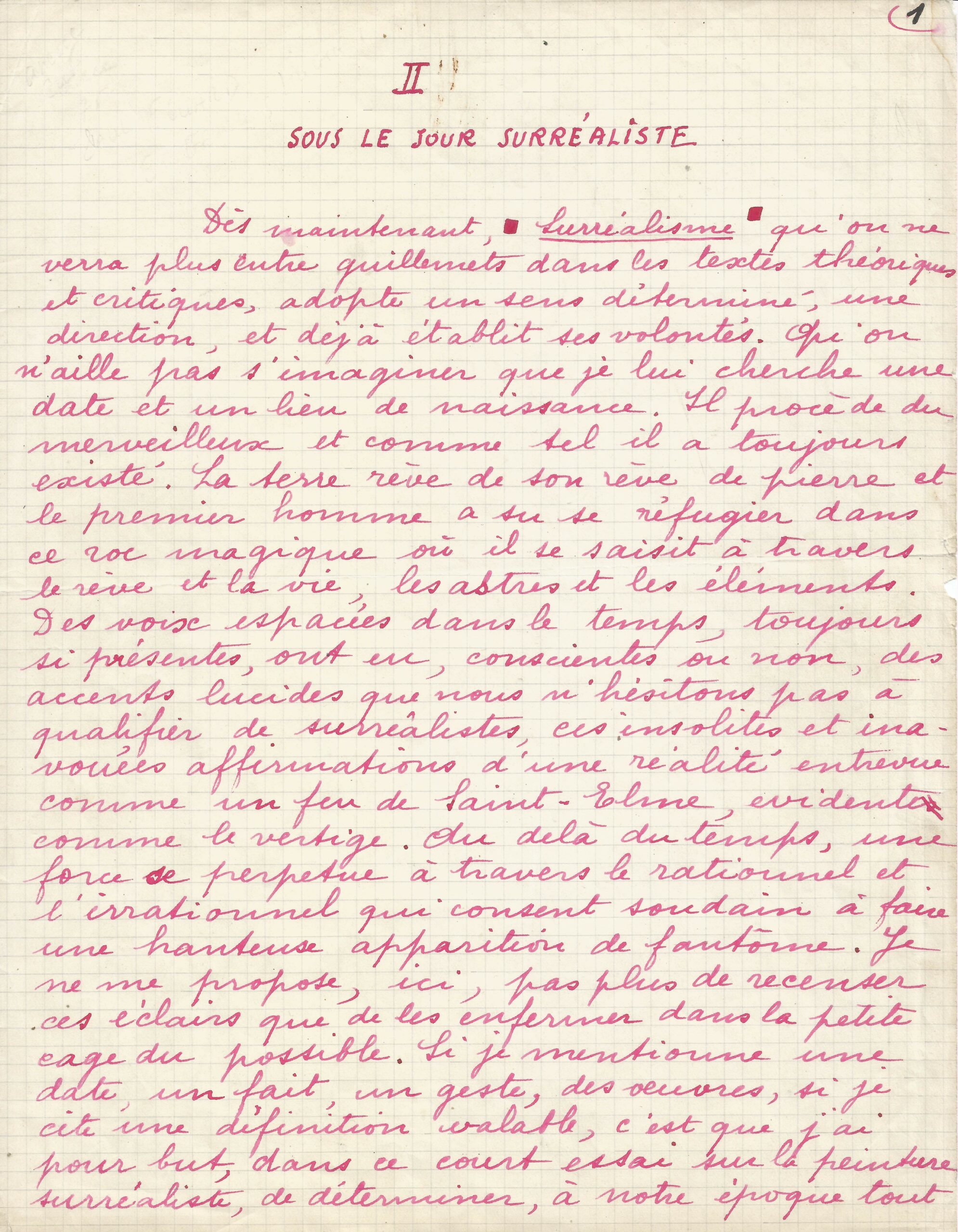

Georges HUGNET (1906.1974)

Partly handwritten manuscript.

In a surreal light.

Eighteen quarto pages in red ink, with erasures, written in two hands.

Eight pages in Hugnet's hand (second hand unidentified).

"Little by little, in this unfathomable realm where surrealism sends its light, formidable degrees of reality are established. »

A long and fascinating manuscript of a study on surrealism (despite a numbering error, the manuscript is complete). Hugnet discusses all the heralds of the movement and its contributions to the history of art.

_____________________________________________________________

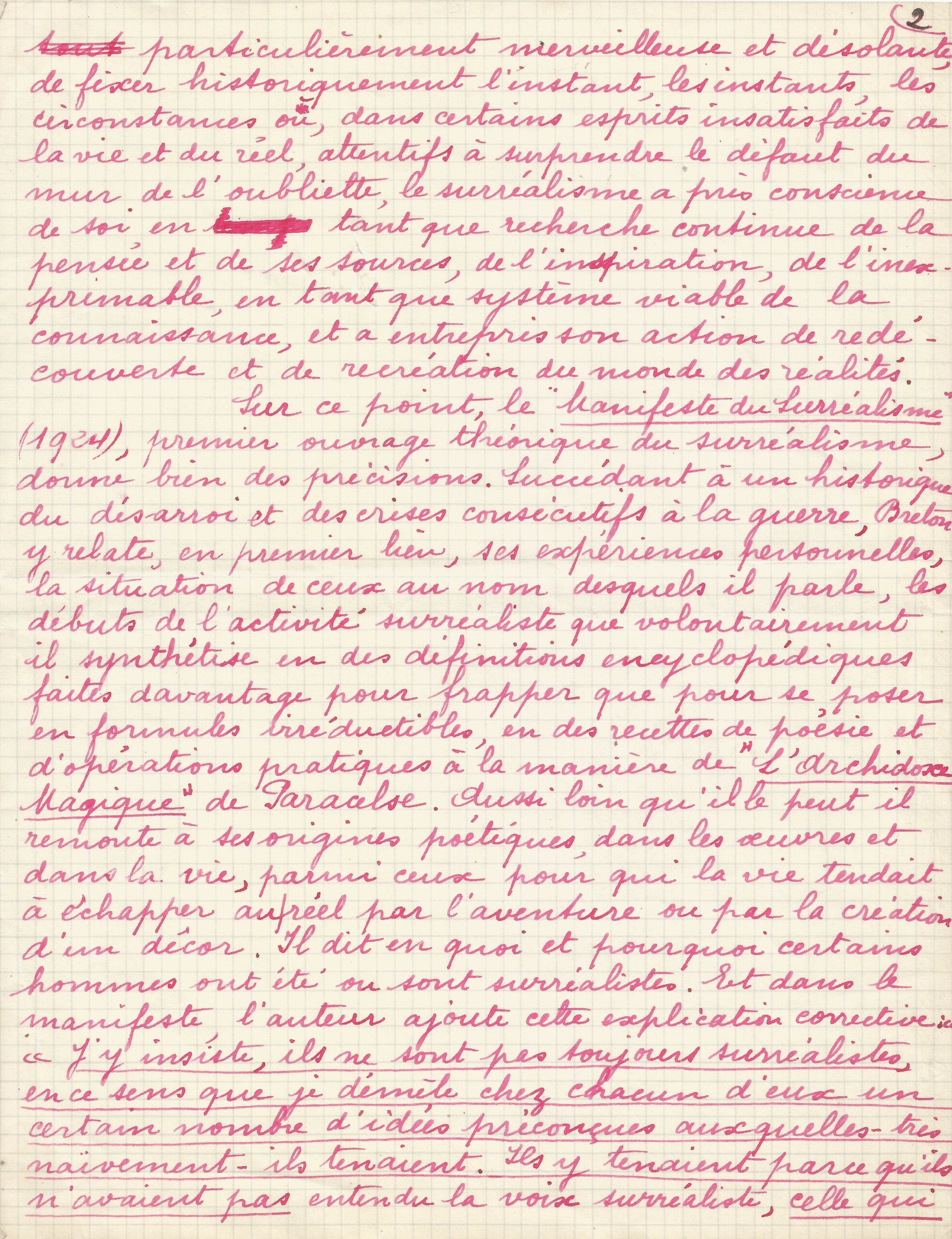

“From now on, Surrealism —which will no longer be seen in quotation marks in theoretical and critical texts—adopts a determined meaning, a direction, and already establishes its will. Let no one imagine that I am seeking a date and place of birth for it. It proceeds from the marvelous, and as such, it has always existed. The earth dreams its dream of stone, and the first man knew how to take refuge in this magical rock where he grasps himself through dream and life, the stars and the elements. Voices spaced out in time, always so present, have had, consciously or unconsciously, lucid accents that we do not hesitate to call surrealist, these unusual and unacknowledged affirmations of a reality glimpsed like St. Elmo's fire, evident as vertigo. Beyond time, a force perpetuates itself through the rational and the irrational, which suddenly consents to make a shameful appearance like a ghost.” My intention here is neither to list these flashes of insight nor to confine them within the narrow confines of possibility. If I mention a date, a fact, a gesture, works of art, if I cite a valid definition, it is because my aim in this short essay on surrealist painting is to determine, in our particularly wondrous and desolate era, to fix historically, the moment, the moments, the circumstances in which, in certain minds dissatisfied with life and reality, attentive to catching the flaw in the wall of oblivion, surrealism became conscious of itself, as a continuous search for thought and its sources, for the inspiration of the inexpressible, as a viable system of knowledge, and undertook its action of rediscovering and recreating the world of realities.

On this point, the " Manifesto of Surrealism " (1924), the first theoretical work of Surrealism, provides considerable detail. Following a history of the disarray and crises resulting from the war, Breton recounts, first and foremost, his personal experiences, the situation of those on whose behalf he speaks , and the beginnings of Surrealist activity, which he deliberately synthesizes into encyclopedic definitions designed more to impress than to establish themselves as irreducible formulas, into recipes for poetry and practical operations in the manner of Paracelsus's " Magic Archidox ." As far back as he can, he traces its poetic origins, in both works and life, among those for whom life tended to escape reality through adventure or the creation of a setting. He explains in what ways and why certain individuals were or are Surrealists . And in the manifesto, the author adds this corrective explanation: “ I insist, they are not always surrealists, in the sense that I unravel in each of them a certain number of preconceived ideas to which – very naively – they clung. They clung to them because they had not heard the surrealist voice, the one that continues to preach on the eve of death and above the storms, because they did not want to serve only to orchestrate the marvelous score. They were instruments too proud, which is why they did not always produce a harmonious sound .

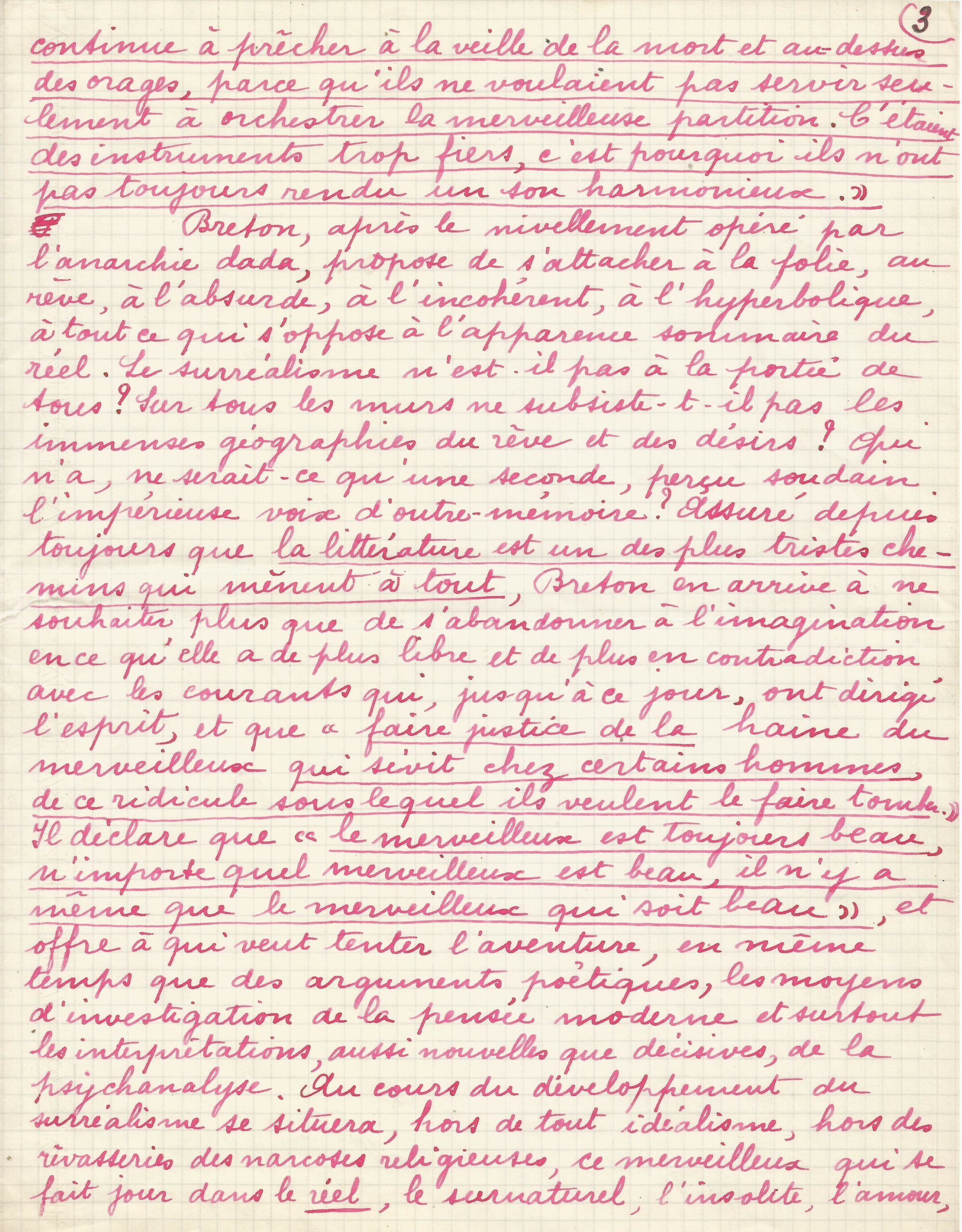

Breton, after the leveling effect of Dada anarchy, proposes to dwell on madness, the absurd, the incoherent , the hyperbolic—on everything that opposes the simplistic appearance of reality. Isn't Surrealism accessible to all? Don't the vast geographies of dreams and desires persist on every wall? Who hasn't, if only for a second, suddenly perceived the imperious voice from beyond memory? Always convinced that literature is one of the saddest paths that leads to everything , Breton comes to desire nothing more than to abandon himself to the imagination in its freest form, in its most contradictory aspect to the currents that, until now, have guided the mind, and to " do justice to the hatred of the marvelous that prevails among certain men, to the ridicule under which they want to reduce it ." He declares that " the marvelous is always beautiful, any marvelous thing is beautiful, indeed only the marvelous is beautiful, " and offers to anyone willing to embark on this adventure, along with poetic arguments, the means of investigating modern thought and, above all, the interpretations of psychoanalysis, as new as they are decisive. In the course of Surrealism's development, beyond all idealism and the reveries of religious narcosis, will lie this marvelous element that emerges in reality : the supernatural, the unusual, love, sleep, hallucination, sexuality, and the disturbances it engenders, madness, chimeras, supposed disorders of all kinds, a view like any other, poetry, blood, chance, fear, escapes of any kind, specters, leisure, the suggestions of dreams, empiricism, and surreality . This marvelous realm, confined within the narrow confines of legends or children's tales, freed from its mirror, brought back to life, now reveals, in its true light, in the surrealist light , the most immediate reality and our relationship to it. In pursuit of the " future resolution of these two seemingly contradictory states, dream and reality, into a kind of absolute reality of surreality," Surrealism has never despaired of this reconciliation. It has striven and will continue to strive, by all means at its disposal, for this identification of opposites, toward which all contemporary discoveries tend. The very trajectory of this attraction through time constitutes the history of Surrealism, which takes action against those who still believe impossible the verification upon which reality depends.

For Surrealism, which is a process of the mind and a means of investigation, operating simultaneously in all fields, for Surrealism, which has established a code of conduct that time has rendered increasingly valid and proven itself, it proves even more difficult than anywhere else to separate the attempts and manifestations of painters from those of writers. It is in the name of humanity, in the name of poetry, in the name of an entire system of creation, that Surrealism raises its voice above all else. Here and there, the same concerns are encountered, whether formal or moral. And their expressions take on a similar character, the same spirit that grants them the same brilliance and the same shadows. Exhibitions, experiments, theoretical and poetic works—everything interpenetrates and justifies itself, everything is exalted. Intellectual preoccupations, attitude in life—this is humanity. The research is collaborative, stems from a shared concern, reflects common anxieties, and tends toward a single goal. Surrealism is more concerned with itself and with time than with individuals. It is not a heroic era, rich in anecdotes; it is a systematic undertaking, a rediscovered light.

Having restored the original vigor to prevailing ideas, Dada, under the impetus of André Breton, saw Surrealism dedicated to revising values. It picked up the thread that had been lost in the immediate past. Immediately, painting, viewed from a new perspective, took on a different character, undergoing a true metamorphosis. In certain painters who had previously been highlighted only for their scandalous nature or originality, Surrealism valued a more revealing vision of a virtual world and more compelling propositions; subversiveness itself acquired a deeper meaning. Thus, Cubism, with its re-creation of reality and its perpetual control, found itself back in vogue. According to Breton, Seurat appeared to him as Surrealist in his subject matter and Picasso in his Cubism . Cubist aesthetics were condemned, but only the negation of reality in favor of a higher reality mattered. From then on, certain objects created by Picasso around 1913 and 1914 took on considerable importance: viewed through a surrealist lens , some works were strangely illuminated. Intentions, processes, attempts, and successes were recorded, while others were deliberately rejected. Some names faded into obscurity, while others emerged or were reborn.

In 1933, Max Ernst wrote: “ The research into the mechanisms of inspiration, mistakenly pursued by the Surrealists, led them to the discovery of certain processes of a poetic nature, capable of removing the creation of the artwork from the dominion of so-called conscious faculties. These means (of captivating reason, taste, and conscious will) resulted in the rigorous application of the definition of Surrealism to drawing, painting, and even, to a certain extent, photography. These processes, some of which, particularly collage, were used before the advent of Surrealism but systematized and modified by it, allowed some to capture on paper or canvas the astonishing image of their thoughts and desires .”

And Paul Éluard, in 1936, tells us: “ It is only through their complexity that objects cease to be indescribable. Picasso knew how to paint the simplest objects in such a way that everyone, when faced with them, became capable, and not only capable but eager, to describe them. For the artist, as for the most uncultured person, there are neither concrete nor abstract forms. There is only communication between what sees and what is seen, an effort of understanding, of relating—sometimes of determining, of creating. To see is to understand, to judge, to distort, to imagine, to forget or to forget oneself, to be or to disappear .”

This choice, made from the outset, this awareness that is created, forms the first stage of Surrealist painting and everything connected with it. Among familiar names like Picasso, Chirico, and Max Ernst, we find, right from the first issue of La Révolution Surréaliste , a new name: André Masson . The latter, who had not participated in any movement, arrived at Surrealism with a series of paintings and drawings, which he had exhibited a few months earlier at the Galerie Simon. Devoid of any exploration of materials, concerned only with a plastic quality, a kind of chemistry of lines, Masson's work, at this time, traces new boundaries of a poetic world of very pure comparisons; there, landscapes have strange human forms, ghosts are present behind transparent vaults, doves live like young girls and daggers like men, beneath shattered capitals, miraculously vanished. Hands animate still lifes, and objects come alive when the eye, gazing at them, loses all control and ceases to fascinate. Then, almost simultaneously, another aspect of the human universe, the surrealist universe, is unveiled by a painter arriving from Catalonia, Joan Miró . At first, Miró delighted in reproducing reality as faithfully as possible, seemingly driven by a concern for wonder. Then, from faces, houses, gardens, and objects, the superfluous falls away to make room for a fantastic, naive, and vibrant reality, imbued with passion and humor, a luxuriant vegetation born from the freest visions and the absolute spontaneity of the hand. These irrevocable paintings, composed without metaphors, were exhibited in 1925 under the auspices of the Surrealist group, with a preface by Benjamin Péret.

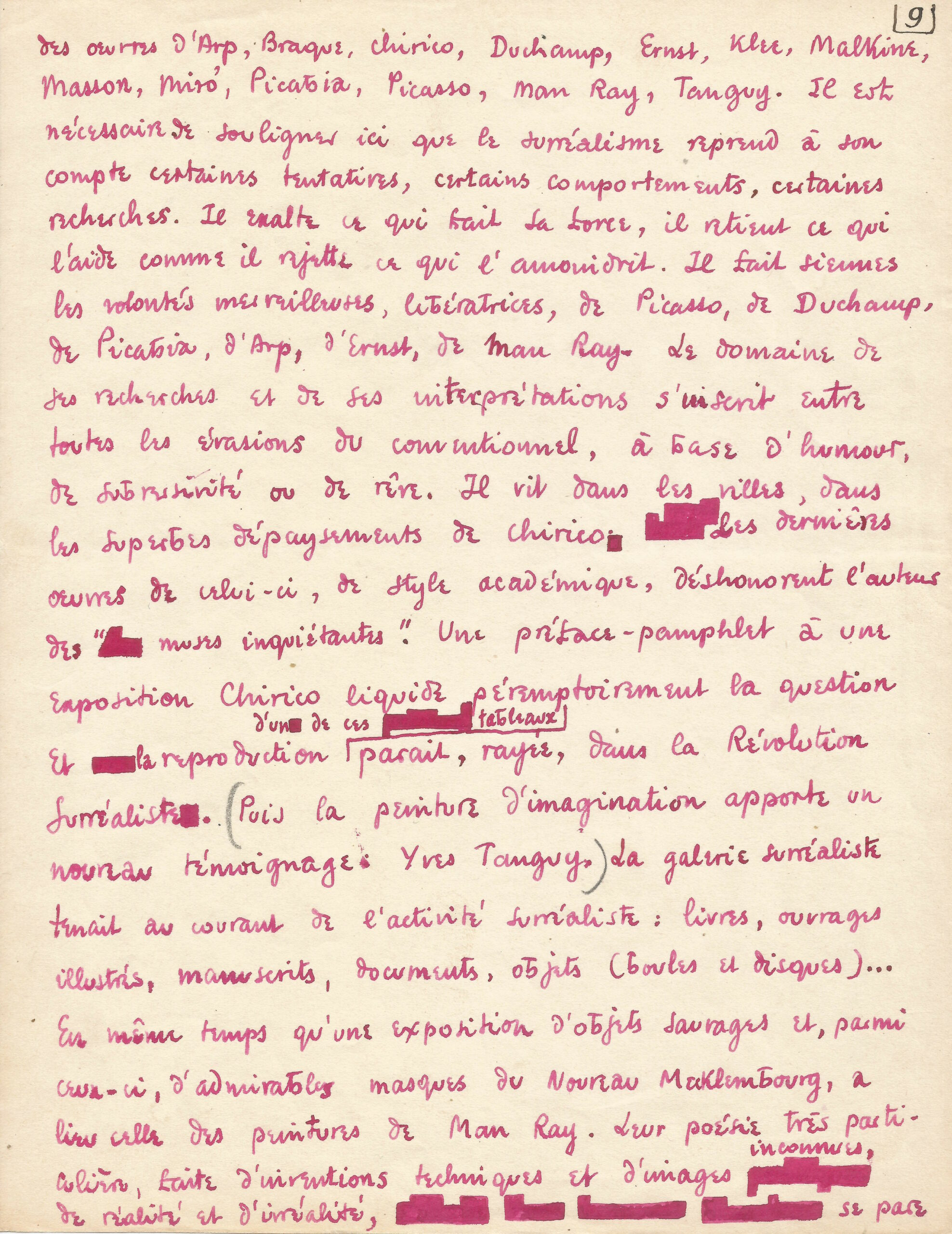

However, while the Surrealist Revolution, whose second issue presented French art as a scarecrow, categorically separated painting from art and linked it to automatism, dreams, and human revelation, the group of poets and painters formed, complemented itself, evolved, and defined itself. Among the reproductions of painters' works were inserted strange photographs, curious documents, mediumistic drawings, and drawings by poets, which accompanied transcribed dreams and automatic writing. The Surrealist atmosphere defined itself; one could say it was so clear that it needed no explanation. André Breton and Robert Desnos collaborated on the preface to the first Surrealist exhibition in November 1925. It brought together Arp, Chirico, Ernst, Klee, Masson, Miró, Picasso, Man Ray, and Pierre Roy. Furthermore, Marx Ernst exhibits his recent paintings alone, accompanied by poems by Éluard, Desnos, Prévert, and Péret. These are magnificent forests through which the most beautiful surrealist images pass. Then the surrealist gallery opens, where one can permanently see works by Arp, Braque, Chirico, Duchamp, Ernst, Klee, Malkine, Masson, Miró, Picabia, Picasso, Man Ray, and Tanguy. It is necessary to emphasize here that surrealism adopts certain attempts, behaviors, and explorations. It exalts what constitutes its strength, retains what aids it, and rejects what diminishes it. It embraces the marvelous, liberating aspirations of Picasso, Duchamp, Picabia, Arp, Ernst, and Man Ray. The scope of his research and interpretations lies between all forms of escape from convention, grounded in humor, subversiveness, and dreams. He lives in cities, in the superb, exotic landscapes of Chirico, whose later works, academic in style, dishonor the author of the "disturbing muses." A preface-pamphlet to a Chirico exhibition peremptorily dismisses the question, and the reproduction of one of his paintings appears to be crossed out in the Surrealist Revolution. (Then, imaginative painting offers further testimony: Yves Tanguy).

The Surrealist gallery kept abreast of Surrealist activity: books, illustrated works, manuscripts, documents, objects (spheres and discs)... Alongside an exhibition of wild objects, including some remarkable masks from New Mecklenburg, was an exhibition of Man Ray's paintings. Their highly distinctive poetry, composed of technical inventions and unfamiliar images, of reality and unreality, is imbued with a mysterious precision, like mathematical sorcery. Shortly afterward, Yves Tanguy presented his first paintings, which were the embodiment of Surrealism.

For ten years, Yves Tanguy, surrendering himself to pure lyrical inspiration, has depicted, painting after painting, an immense and unsettling panorama. A unique, complete universe, resembling only itself, where nothing is recognizable in anything else, where one can see everything and nothing, dead cities or cities in embryo, ruined marbles and dreamlike termite mounds, where the law of gravity is a game and the horizon a final concession. Between the technical discoveries of a Max Ernst and the extreme manual freedom of a Miró, for whom automatism is imperative in both cases, Tanguy paints without artifice and without premeditation, but with the meticulousness of a craftsman or a coral reef. During an inquiry into painting, Tanguy declared: " I expect nothing from my reflection, but I am sure of my reflexes . " Tanguy's painting is infallible. Before the blank canvas, dream and instinct guide his hand. A stain is born, an object appears within it, spreading and evolving. A strange landscape populates the desert, which a beautiful light recedes. Its first exhibition is prefaced by Breton.

At the same time, Pierre Roy exhibited his paintings in a setting reminiscent of Chirico's. Aragon wrote the preface. Among the Surrealist publications of this period, the most important after Éluard's astonishing "Répétitions" adorned with collages by Marx Ernst, were Péret's " Dormir dormir dans les pierres ," illustrated by Tanguy, and Éluard's " Défense de savoir, " featuring a frontispiece by Chirico. The Surrealist gallery presented paintings by Malkine. Several exhibitions of Marx Ernst's work took place. Breton explored Surrealist pictorial activity in his *Surréalisme et la Peinture* . There, he revisited the question in its essence, connecting with the artists in their intentions. In it, he expresses the admiration he feels, regardless of any differences of opinion or concerns that may separate them, for certain painters who, under one label or another, through various intellectual or technical means, have liberated painting from its less-than-human role. Re-examining the problem of reality, he discerns those who have touched upon the true reality of things, those who have gone to the heart of the matter, to the very core of the great trees in the forest of the marvelous. By highlighting what moves and inspires him in certain painters, he expresses the hope he places in painting. “ A very narrow conception of imitation, given as the goal of art, is at the root of the serious misunderstanding that we see persisting to this day. Based on the belief that man is only capable of reproducing, with varying degrees of success, the image of what moves him, some painters have been rather uncompromising in their choice of models.” The mistake was to think that the model could only be found in the external world, or even that it could only be found there. Certainly, human sensibility can confer upon the most vulgar-looking object a completely unexpected distinction; it is nonetheless true that it is a poor use of the magical power of representation that some possess to use it for the preservation or reinforcement of what would exist without them. This is an inexcusable abdication. In any case, it is impossible, in the current state of thought, especially when the external world appears increasingly suspect, to consent to such a sacrifice. The plastic work, in order to respond to the necessity of an absolute revision of real values on which all minds now agree, will therefore refer to a purely internal model, or it will not exist at all .

While describing the current state of Surrealism in its visual manifestations, André Breton, with his characteristic foresight and extraordinary lucidity, defines Surrealist painting by assigning it a purpose, revealing its inherent magical power, and uncovering the problems it faces. In this respect, *Surrealism and Painting* is a seminal work . Like all Surrealist expressions, painting becomes a document in which humanity reveals itself, where it formulates a hypothesis that serves as the basis for all possible inferences. Since humanity has lost itself, it must search for itself, trace its way back to itself. Here, as elsewhere, as in poetry, as in images, humanity must unlock the secret passage, find the missing piece in the perpetual clock.

Certain processes—the use of elements foreign to painting, drawings, mechanics…—and certain experiments, as we have seen, had only aimed to extricate painting from its rut or, under the implosion of Dada, to destroy notions of beauty, quality, and purity, to exalt disorder, to systematize everything at all costs. Systematized, directed, and exploited by Surrealism, they no longer tend toward destruction but become means of investigation. Surrealist written games—questions and answers, sentences created collaboratively—are transposed into drawings, and this is how curious characters are born: the Exquisite Corpses . When Surrealism interrogates chance, it is to obtain oracular answers. The collage technique, introduced, or at least used very specifically, for the first time by Max Ernst, is very instructive in this regard. To this revealing process, Max Ernst added another: rubbing, where the secrets invisible to the naked eye of objects appear endlessly.

To the Cubist collages, where a purely aesthetic concern reigns supreme, Surrealist collages add the supernatural spark of a mechanical, anonymous freedom that liberates painting from itself. The opportune figuration, within the confines of a frame, of the element, taken from life, alive—wallpaper, newspaper, poster, canvas, faux marble and faux wood, sand, string—had freed painting from its ideal and reopened the question of reality, the wretched misunderstanding of truth. The public's "that's not painting" alone proves the colossal reality of the collage, the surrealism of the collage itself. The transfusion of materials—a guitar made of iron, of canvas—proclaims the reality of the object. Tristan Tzara aptly wrote: “ A shape cut from a newspaper and incorporated into a drawing or painting incorporates the commonplace, a piece of everyday, commonplace reality, in relation to another reality, constructed by the mind. The difference in materials that the eye is able to transpose into tactile sensation gives a new depth to the painting, where weight is inscribed with mathematical precision in the symbol of volume, and its density, its taste on the tongue, its consistency, place us before a unique reality in a world created by the power of the mind and of dreams. ” Surrealist collages, and particularly the admirable collages with captions by Max Ernst ( The Woman with 100 Heads , 1929; Dreams of a Little Girl Who Wanted to Enter the Carmel , 1930; A Week of Kindness , 1934), are the fruit of imagination, of the most unquestionable inspiration; they transform the mind into matter and make themselves accessible to all. The incorporation into a painting of an element foreign to painting reconciles the irreconcilable. It is from this destroyed contradiction that art must die, and it dies in the works of the insane when they tyrannically equate the external appearance with dreamlike delirium. To this identification, Surrealism brings the freedom of experience and reasoning, a shift from the unconscious to the conscious, a will to analysis that allows research to proceed under the auspices of a marvel that is both poetic and critical. “ The painter ,” declares Louis Aragon in * La Peinture au défi* ( if we must still call him that), “is no longer bound to his painting by a mysterious physical kinship, analogous to generation. And from these negations, we see born an affirmative idea, which is what we call the personality of choice. A manufactured object can just as easily be incorporated into a painting, constitute the painting itself. For Picabia, an electric lamp becomes a young girl.” We see that painters here begin to use objects like words. The new magicians have reinvented incantation . This personality of choice, in effect, distinguishes painters just as the choice of words and the recurrence of certain images, despite chance and automatism, separates poets, even in a state of unconsciousness. Doing justice to hallucination, it is expressed through the repeated use of certain commonplaces, certain expressions that are then personal. This choice betrays the man; and it is precisely this betrayal that Surrealism seeks to address.

Salvador Dalí's poetic, pictorial, and critical contributions steered Surrealist research in a particular direction and gave a powerful impetus to endeavors that had previously been approached only timidly. His work is an immense, carnivorous flower magnified by the Surrealist sun. More moved by the lyrical expression of certain canvases by Ernst and Tanguy than won over by their artistic techniques, and pushing certain declarations of the first Manifesto , he deliberately yielded to dreams, to the hallucinatory element, which he represented as faithfully and subtly as possible. Hence his taste for chromolithography, nature's most colorful, complete, and least accidental invitation. Disdaining any search for materiality and any intervention of commonplaces , his style , his pictorial gift, are at the service of delirium. Dalí escapes into trompe-l'œil. He created for himself a world of intensity where simulations, traumas, neuroses, sexual phenomena, and repressions play out … True to himself, if he moves from collage to chromolithograph, from the ready-made to the invitation to be mistaken for it, he also moves from Chirico and Picasso to Millet and Meissonnier along a paranoid path. His attempt, however extremely fruitful, cannot be generalized. Nevertheless, it must be admitted that the angle from which he positions himself, his vision of painting and its outcomes, what pushes him towards the anti-artistic, towards handheld instant photography and towards a double-edged art, his system of subjective criticism, his obsessive interpretation of the most common and widespread works, as well as his principled acceptance of all aberrations, in his written works or his painting, and his respect for the dream in its contradictory integrity, are in truth essentially surrealist documents. Tempted by the utterly demented appearance of certain periods in art, he feels irresistibly drawn, as Surrealism has always been, to madness, to fits of hysteria, to mediumistic cases, to the manic emotion of the decay of this Art Nouveau style with its architectures molded by irrational tresses, its sleepwalking furniture of immeasurable flowers, its immense confusions of the mentally deficient, its fluctuating objections of deformities. The rehabilitation of Art Nouveau , of this debilitating style and its debilitating tendencies, striving towards an impossible kind of collective hallucination, falls very strictly within the domain of Surrealist criticism and its interpretations, just like all manifestations of a neurotic nature, and anything that might require some kind of investigation. Thus, for example, of these pre-war maps, bizarre to say the least, always poetic, Éluard says that " commissioned by the exploiters to distract the exploited, they do not constitute popular art. At most, they are the small change of art in general and of poetry. But this small change sometimes gives the idea of gold. "

All these concerns, which present no contradictions, coordinate themselves and, properly speaking, profoundly form the domain of the modern marvel of surrealism. Seen from this platform, everything is interconnected: from the unusual to the anti-artistic, from chance and dreams to automatic writing and the delirium of critical interpretation to delirious symbols, from the painting to the everyday object, from the denatured object to deliberate strangeness, from organization to disorganization, from the poem to everyday life… A history of grandiose desires, reveries of this world, traversed by invisible rays and magnetic flashes, unsettling lives unfold within life. Little by little, in this unfathomable realm where surrealism casts its light, formidable degrees of reality are established.