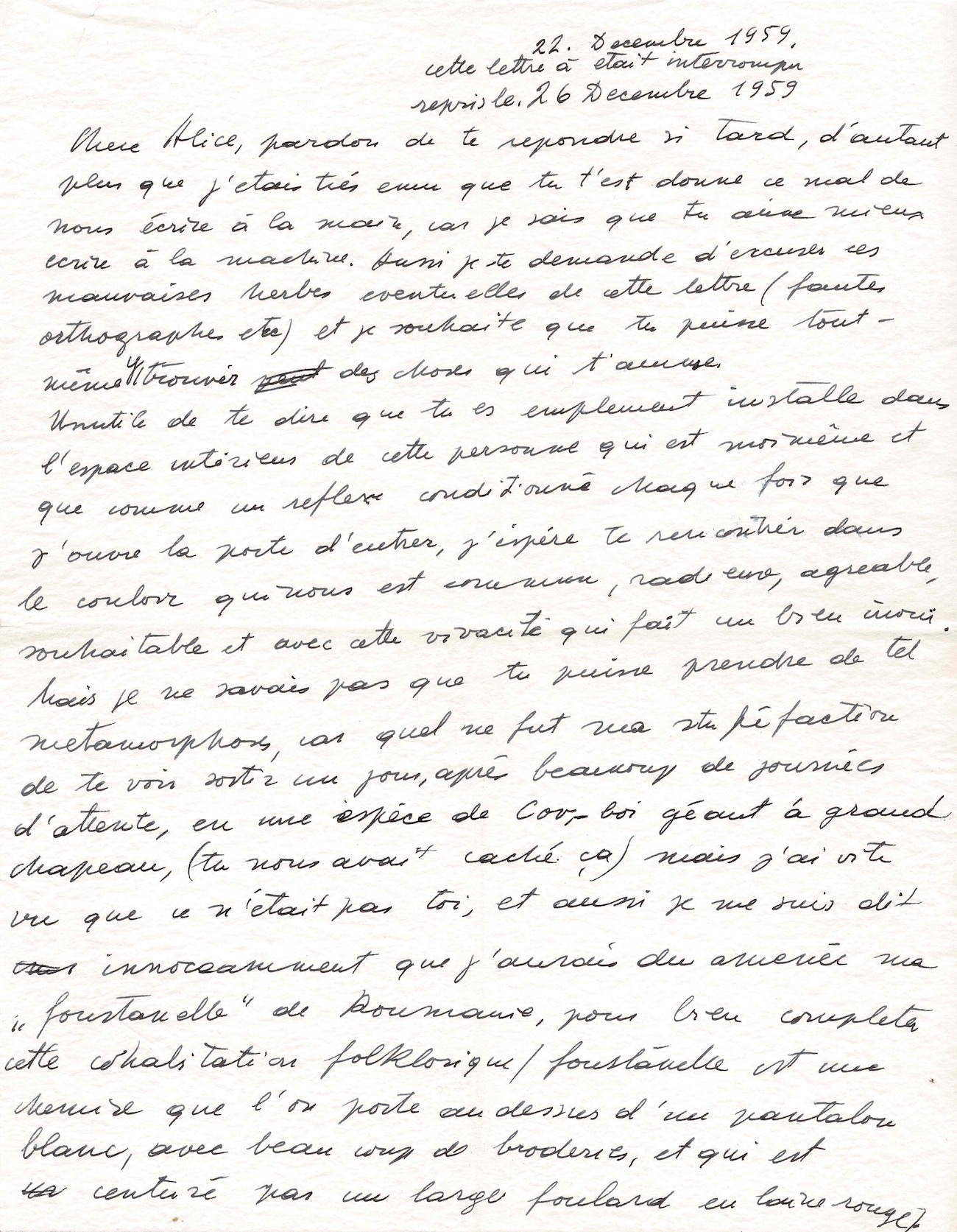

Victor Brauner (1903.1966)

Autographed letter signed to Alice Rewald

Eight pages in quarto.

No location. December 22-26, 1959.

"One of the most extravagant things was that evening commemorating the Marquis de Sade's will, a surreal ceremony that took place in a sumptuous apartment in the Bois de Boulogne."

An extraordinary letter from Brauner recounting in detail the events of a surreal evening in memory of the Marquis de Sade.

___________________________________________________________

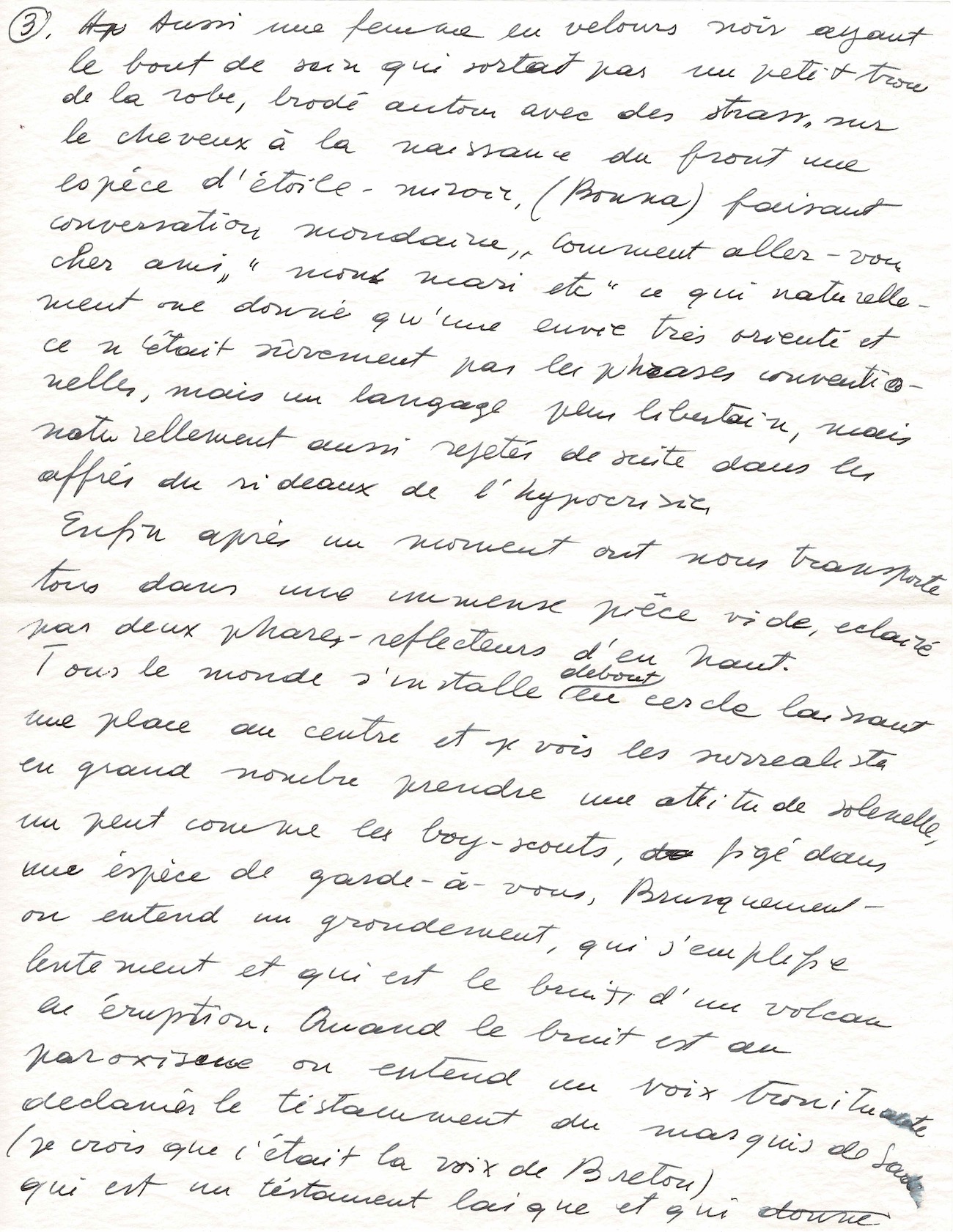

"Dear Alice, I apologize for the late reply, especially since I was very touched that you took the trouble to write to us by hand, as I know you prefer typing. Therefore, I ask you to excuse any possible flaws in this letter (spelling mistakes, etc.) and I hope that you will still find something in it that amuses you.".

Needless to say, you're completely settled into the inner space of this person who is me, and like a conditioned reflex, every time I open the front door, I hope to meet you in the hallway we share, radiant, pleasant, desirable, and with that vivacity that feels so wonderful. But I didn't know you could undergo such metamorphoses, because imagine my astonishment when one day, after many days of waiting, you emerged as a kind of giant Cov-boi with a large hat (you had kept that a secret from us), but I quickly realized it wasn't you, and I also innocently thought that I should have brought my Romanian "fourtanelle" to complete this folkloric cohabitation. (A fourtanelle is a shirt worn over white trousers, with lots of embroidery, and cinched with a wide red wool scarf.).

In any case, you should know that you are present in my inner world, and that in all these daydreams we conduct outside of all conventional boundaries, you have an active role to which you are drawn against your will. But if this path of emotional digression continues, I won't write to you what I wanted, also some facts that explain why we haven't been bored in Paris lately.

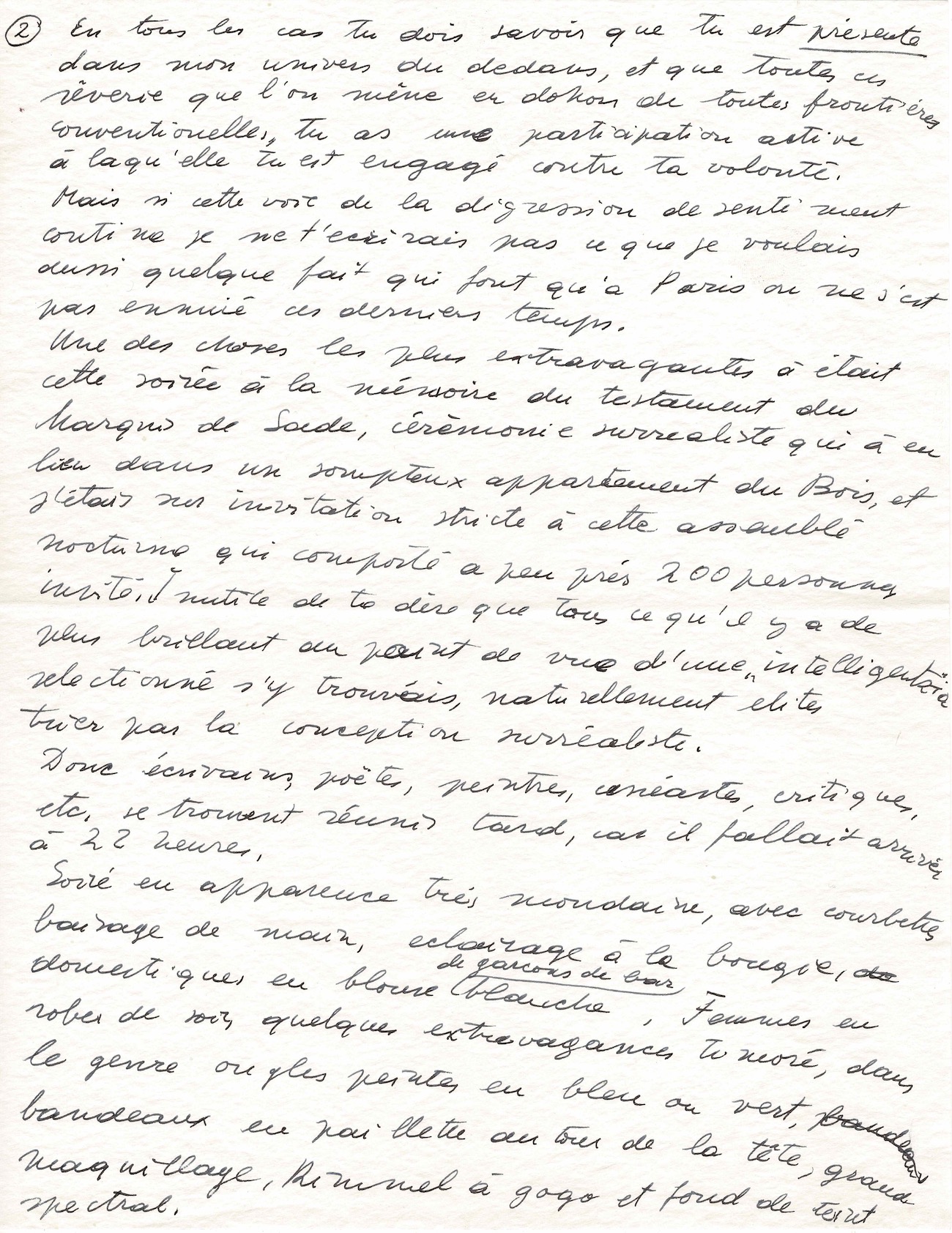

One of the most extravagant things was that evening commemorating the Marquis de Sade's will, a surreal ceremony held in a sumptuous apartment in the Bois de Boulogne , and I was by strict invitation to this nocturnal gathering of roughly 200 invited guests. Needless to say, all the brightest minds, a select intelligentsia, were there, naturally elites filtered through the surrealist lens.

So writers, poets, painters, filmmakers, critics, and so on, found themselves gathered late, as they had to arrive by 10 p.m. It was an apparently very sophisticated evening, with bowing and kissing hands, candlelight, and servants in white barman's smocks. The women wore evening gowns, and there were a few restrained extravagances, such as blue or green painted nails, sequined headbands, heavy makeup, lots of mascara, and spectral foundation.

Also a woman in black velvet with the tip of her breast peeking out of a small hole in the dress, embroidered around with rhinestones, on her hair at the base of her forehead a kind of mirror-star, making worldly conversation "how are you dear friend" "my husband etc" which naturally only gives a very biased desire and it was certainly not the conventional phrases, but a more libertine language, but naturally also immediately rejected into the throes of the curtain of hypocrisy.

Finally, after a while, we were all led into a vast, empty room, illuminated by two reflector-headlights from above. Everyone stood in a circle, leaving a space in the center, and I saw a large number of Surrealists adopt a solemn posture, a bit like Boy Scouts, frozen in a kind of attention pose. Suddenly, we heard a rumbling sound, which slowly grew louder and was the sound of a volcano erupting. When the noise reached its peak, we heard a booming voice reciting the will of the Marquis de Sade (I think it was Breton's voice), a secular will in which he bequeathed his fortune to his servants and other poor people, and asked to be buried without religious rites.

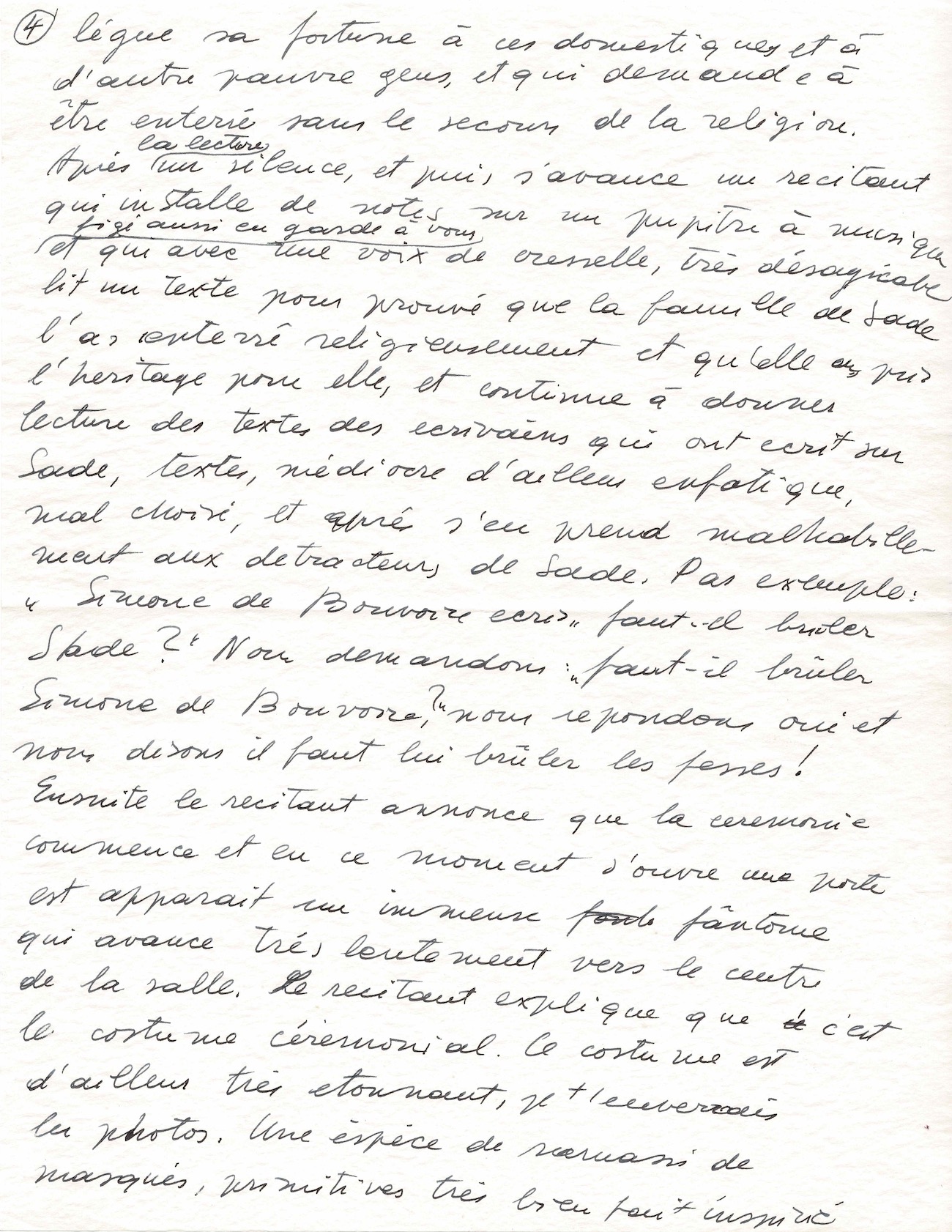

After the reading, there was silence, and then a narrator stepped forward, settling himself on a music stand, also frozen at attention, and, with a grating, unpleasant voice, read a text to prove that Sade's family had given him a religious burial and had taken the inheritance for themselves. He continued reading texts by writers who had written about Sade—mediocre, tedious, and poorly chosen texts—and then clumsily attacked Sade's detractors. For example: " Simone de Bauvoire writes, 'Should Sade be burned?' We ask, 'Should Simone de Bauvoire be burned?' We answer yes, and we say, 'We must burn her buttocks!'"

Then the narrator announces that the ceremony is beginning, and at that moment a door opens and an immense phantom appears, advancing very slowly towards the center of the room. The narrator explains that this is the ceremonial costume. This costume is quite astonishing; I'll send you the photos. A kind of collection of masks, primitive and very well made, inspired by British Columbian masks, and surrealist imagery reminiscent of Max Ernst and probably myself (I've been told there's a strong resemblance to my characters). This apparition is quite impressive, and as this figure advances, it emits a howl with each step: one foot makes a high-pitched, shrill sound, the other a low, thunderous one. The narrator explains that what this figure is dragging behind it is Sade's coffin , and continues throughout to explain the symbols found on this large costume. A woman dressed in black with a headband around her hair and who looks very Salvation Army, puritanical appears and begins to remove each part of this costume, which the living character in this immense mobile scaffolding is wearing.

In what they call the coffin, there is, of course, an enormous penis; from the small hole at its tip emerge five black petals, in the center of which are the five letters of the word love.

Throughout this time, the narrator draws our attention to every detail, and the woman in black, a kind of vestal virgin of the ceremony, removes each part of the costume, beginning with the coffin, which she skillfully dismantles, placing each individual piece on the wall. Thus, she demonstrates the word "love," holding this immense black phallus for a few moments. After the coffin, the figure wearing a multitude of superimposed masks is gradually undressed, each piece being removed (it is always the woman who performs this undressing), and placed on the wall each time.

The figure wears an enormous black penis (in fact, all the costumes are volcanic black with dark blue and purple highlights), which is then removed and placed against the wall, revealing another, smaller penis. Finally, there is a black undershirt with a kind of mask covering the face—extremely organic, gelatinous, and impressive—from which two enormous eyes are visible. The woman at the ceremony then helps the figure remove the undershirt, leaving him naked. He is very handsome, painted black and streaked with purple arrows that ascend his body toward his heart. In place of the heart is a red star bearing a double-headed eagle, the emblem of the Marquis de Sade. (I forgot to mention to you that the servant in the office lights a fire in a tripod container, where she places a branding iron which has as a handle a male sex organ always in erect form.) The character has his eyelids painted in violet red and the backs of his ears also red.

Meanwhile, the narrator continues to describe each sign in detail, and drawing our attention to his enormous penis, the officiant, the actor in this spectacle, guides it up his stomach with a nylon thread attached to a finger, raising his hand towards his heart. This reveals more symbols below his penis: a red hole containing an hourglass filled with black volcanic sand from Stromboli. After the narrator stops, the officiant also pauses, and after a moment of stillness and silence, he tears off the red star with his left hand, leaving in its place a white mark on his skin, a star on his skin. (As I told you, he is painted with volcanic black.) He lets out a howl, seizes the red-hot branding iron, and, shouting something that ends with "Sade," brands himself with the name Sade over his heart. He brandishes the iron and says, "To whom?" "Silence, and suddenly Matta, who was a little drunk and very childish, rushed forward and, opening his shirt, marked himself as well. There you have the facts, recounted like a news item; it's up to you to draw your own conclusions. In any case, no Surrealist responded to the invitation to brand themselves. Then we went into the living room, and the evening ended very politely with whiskey and champagne and mediocre conversation. The next day, André Breton phoned me with a text rehabilitating Matta and myself, which I'll send you without comment. Victor. "