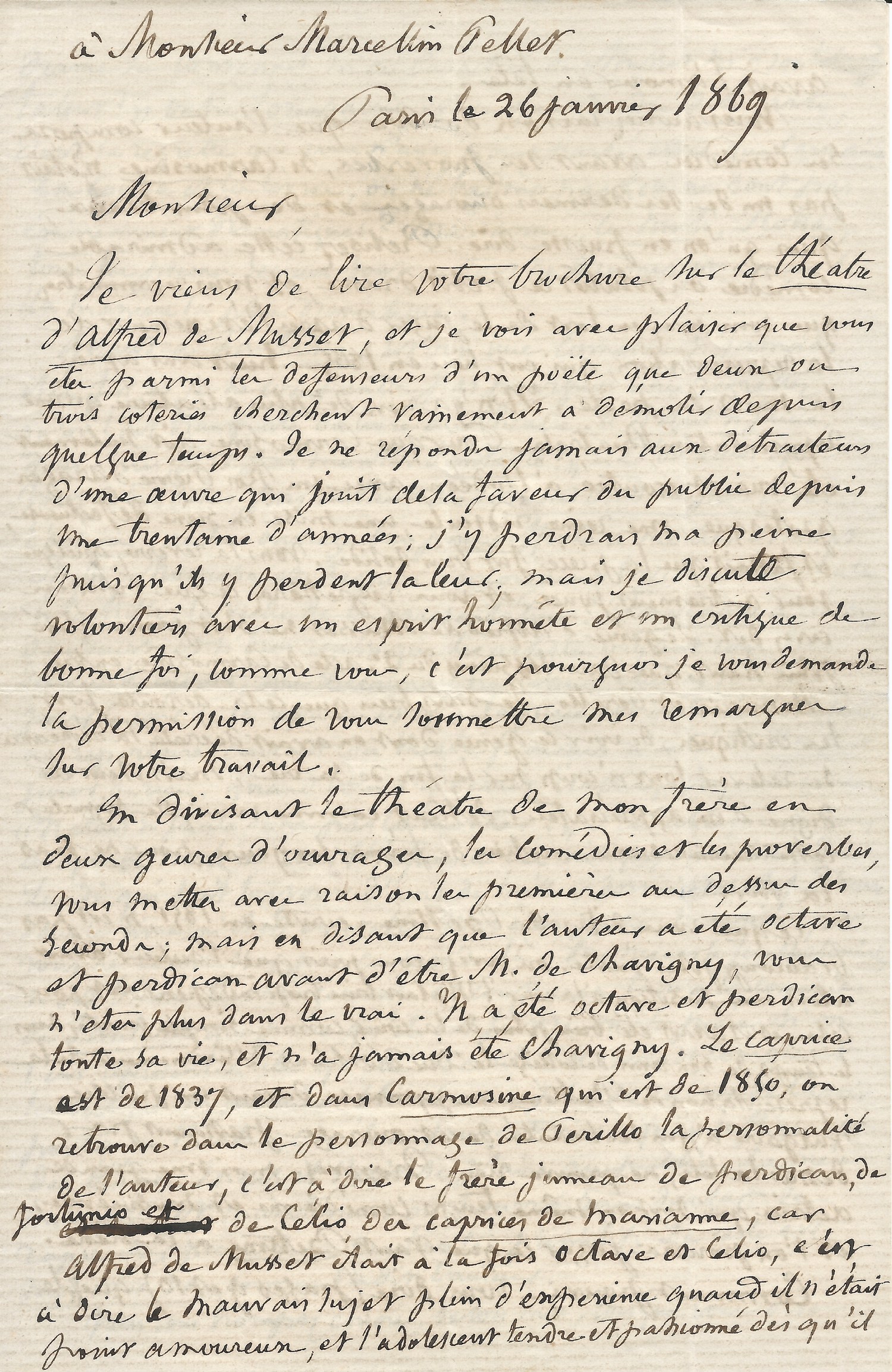

Paul de Musset (1804.1880)

Autographed letter signed to Marcellin Pellet.

Four octavo pages. Remnants of a collector's stamp.

Paris, January 26, 1869.

“… that my brother be left alone and that no one seek to destroy his statue to make a pedestal for other poets …”

Alfred de Musset's theatre and creativity valiantly defended by his brother.

_______________________________________________

"Sir, I have just read your pamphlet on the plays of Alfred de Musset , and I am pleased to see that you are among the defenders of a poet whom two or three cliques have been vainly trying to destroy for some time now. I never respond to the detractors of a work that has enjoyed public favor for some thirty years; I would be wasting my time since they are wasting theirs, but I gladly discuss matters with an honest mind and a critic of good faith, like yourself, which is why I ask your permission to submit my remarks on your work."

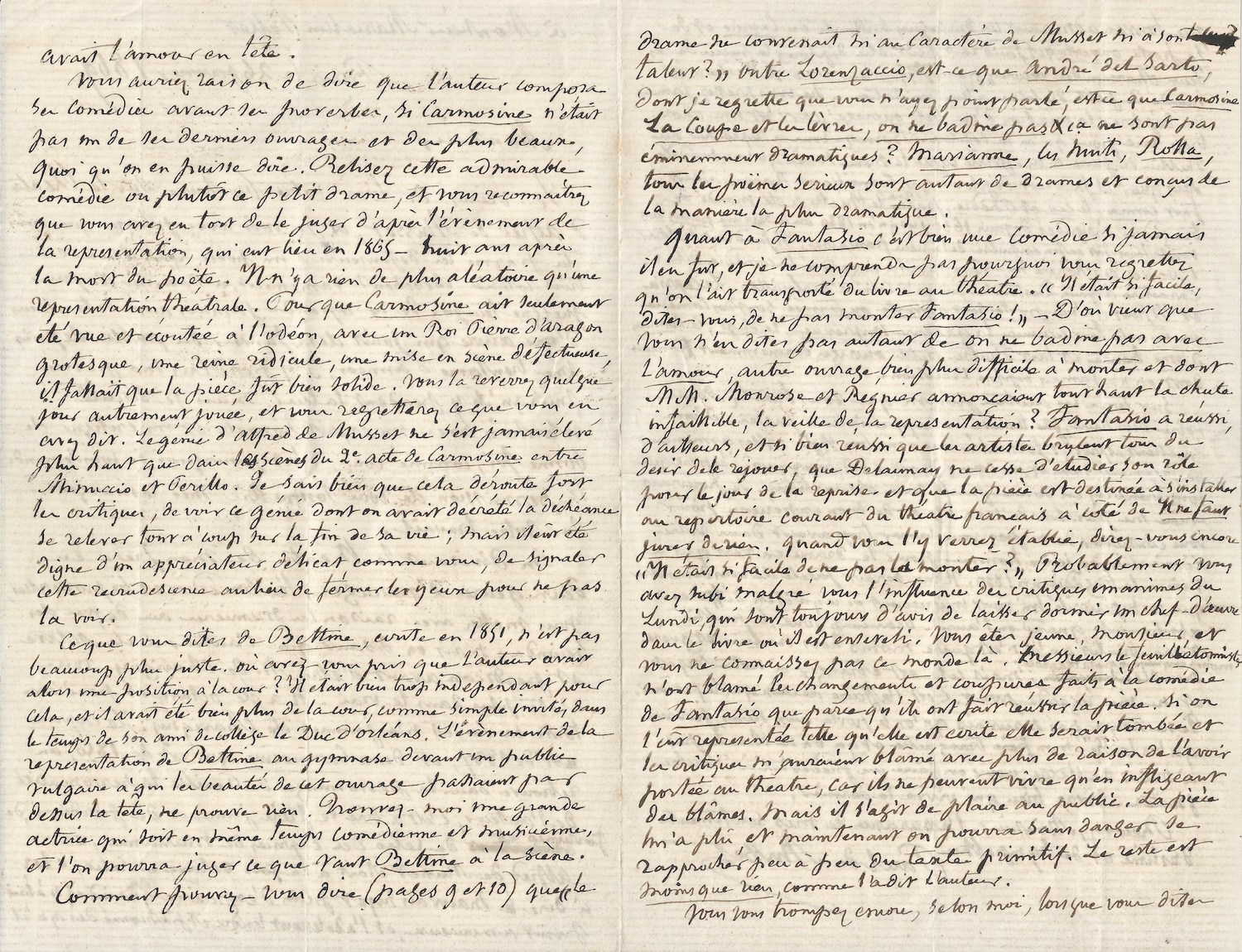

By dividing my brother's plays into two genres, comedies and proverbs, you rightly place the former above the latter; but by saying that the author was Octave and Perdican before he was Monsieur de Chavigny, you are mistaken. He was Octave and Perdican all his life, and was never Chavigny. * Le Caprice * dates from 1837, and in *Carmosine* , which dates from 1850, we find in the character of Perillo the author's own personality, that is to say, the twin brother of Perdican, Fortunio, and Célio from *Les Caprices de Marianne* , for Alfred de Musset was both Octave and Célio, that is to say, the rogue full of experience when he wasn't in love, and the tender and passionate adolescent as soon as love was on his mind.

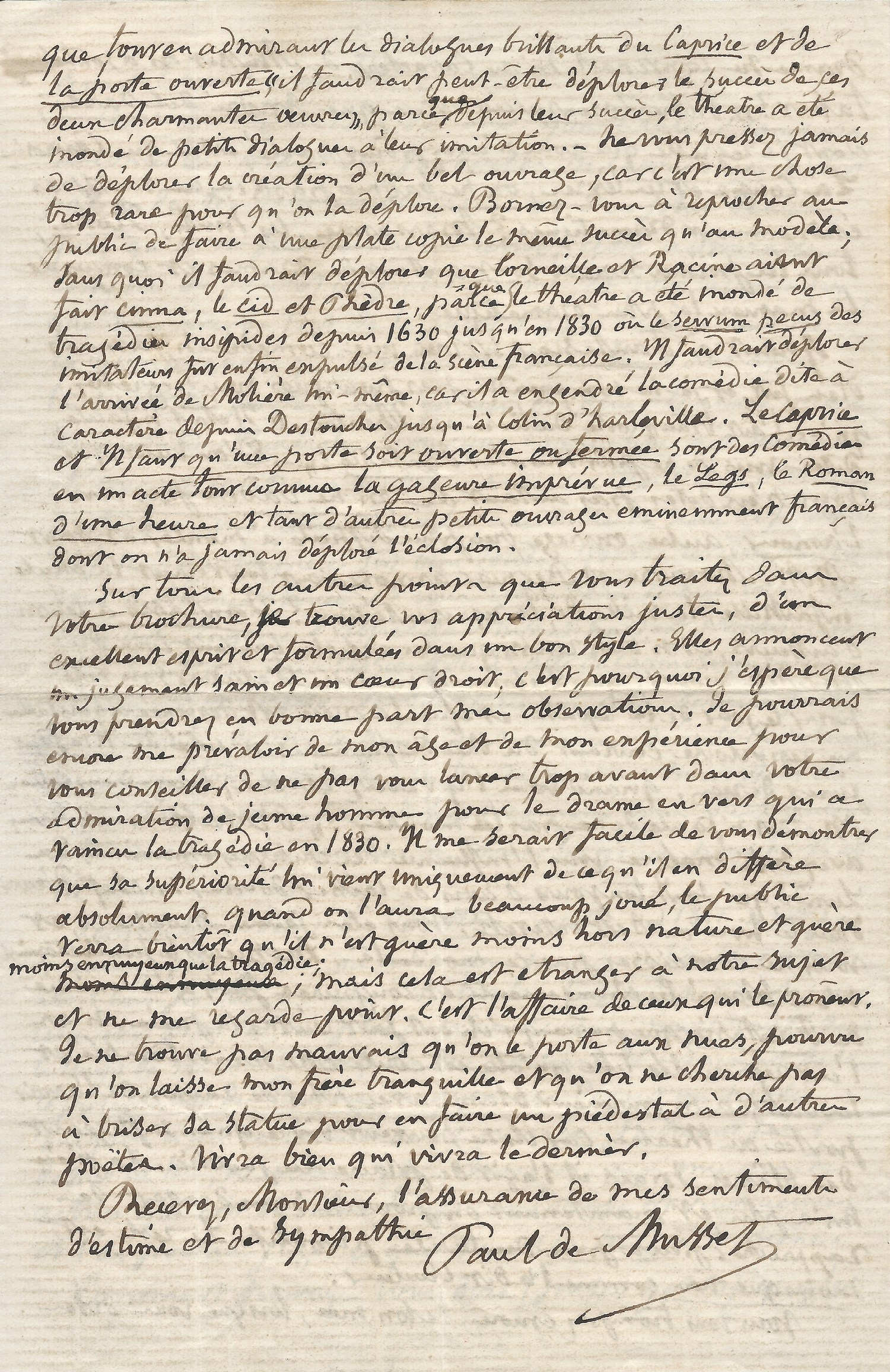

You would be right to say that the author composed his comedies before his proverbs, if Carmosine weren't one of his last and finest works, whatever anyone might say. Reread this admirable comedy, or rather this little drama, and you will recognize that you were wrong to judge it based on the event of the performance that took place in 1865—eight years after the poet's death. There is nothing more unpredictable than a theatrical performance. For Carmosine to have even been seen and heard at the Odéon, with a grotesque King Peter of Aragon, a ridiculous queen, and flawed staging, the play must have been quite solid. You will see it performed differently someday, and you will regret what you said about it. Alfred de Musset's genius never soared higher than in the scenes of Act 2 of Carmosine between Minuccio and Perillo. I know that it greatly baffles critics to see this genius, whose downfall had been decreed, suddenly rise again at the end of his life; but it would have been worthy of a discerning connoisseur like yourself to point out this resurgence instead of closing your eyes to avoid seeing it.

What you say about Bettine , written in 1851, isn't much more accurate. Where did you get the idea that the author held a position at court at that time? He was far too independent for that, and he had been much more involved at court, as a mere guest, during the time of his school friend, the Duke of Orléans. The fact that Bettine in the gymnasium before a vulgar audience who were completely oblivious to the beauty of the work proves nothing. Find me a great actress who is also a comedian and a musician, and then we can judge Bettine's on stage.

How can you say (pages 9 and 10) that "drama was unsuited to both Musset's character and his talent"? Besides Lorenzaccio , aren't André del Sarto , which I regret you didn't mention, Carmosine, La Coupe et les Lèvres , and On ne badine pas eminently dramatic? Marianne , Les Nuits , Roma —all his serious poems are dramas, conceived in the most dramatic manner.

As for Fantasio, it is indeed a comedy if ever there was one, and I don't understand why you regret its adaptation from book to stage. "It would have been so easy," you say, "not to stage Fantasio !" – Why then do you not say the same of On ne badine pas avec l'amour (No Trifling with Love) , another work far more difficult to stage, whose inevitable failure Messrs. Monrose and Régnier loudly proclaimed the day before the performance? Fantasio , moreover, succeeded, and succeeded so well that the actors are all burning with the desire to perform it again , that Delaunay is constantly studying his role for the revival, and that the play is destined to become a regular feature of the French theater repertoire, alongside Il ne faut jurer de rien (Never Swear to Anything ). When you see it established there, will you still say, "It would have been so easy not to stage it?"

You have probably been unwittingly influenced by the unanimous Monday critics, who always seem to think a masterpiece should be left to slumber in the book where it lies buried. You are young, sir, and you don't know that world. The columnists only criticized the changes and cuts made to the comedy of Fantasio because they made the play a success. If it had been performed as written, it would have flopped, and the critics would have had even more reason to blame me for bringing it to the stage, since they can only survive by inflicting blame. But the point is to please the public. I liked the play, and now we can safely return little by little to the original text. The rest is worthless, as the author himself said .

You are mistaken, in my opinion, when you say that while admiring the brilliant dialogues of *Le Caprice* and * La Porte Ouverte* , "one should perhaps lament the success of these two charming works," because since their success, the theater has been flooded with short dialogues imitating them. Never be quick to lament the creation of a fine work, for it is too rare a thing to be lamented. Confine yourself to reproaching the public for giving a flat copy the same success as the original; otherwise, one would have to lament that Corneille and Racine wrote *Cinna* , *Le Cid* , and *Phèdre* , because the theater was flooded with insipid tragedies from 1630 until 1830, when the servile herd of imitators was finally expelled from the French stage. One would have to lament the arrival of Molière himself, for he gave birth to the so-called character comedy from Destouches to Colin d'Harleville. Le Caprice and Il faut qu’une porte soit ouverte ou fermée are one-act comedies, as are La Gageure imprévue , Le Legs , Le Roman d'une heure and so many other eminently French little works whose emergence has never been regretted.

On all the other points you address in your pamphlet, I find your assessments accurate, insightful, and well-written. They reveal sound judgment and an upright heart, which is why I hope you will take my observations to heart. I could also use my age and experience to advise you against indulging your youthful admiration for the verse drama that supposedly triumphed over tragedy in 1830. It would be easy for me to demonstrate that its superiority stems solely from its absolute difference from tragedy. Once it has been performed extensively, the public will soon see that it is scarcely less unnatural and scarcely less tedious than tragedy; but that is beside the point and does not concern me. It is a matter for those who champion it. I don't mind its being lauded, provided my brother is left in peace and no one tries to destroy his legacy to create a pedestal for other poets . He who lives last will live best. Please accept, Sir, the assurance of my esteem and sympathy. Paul de Musset

_______________________________________________

By breaking free from traditional representational conventions to write, in particular, "armchair plays," Alfred de Musset revolutionized the art of theatre in his time, enabling new dramaturgies and stage spaces.

His work, favorably received by the public, sometimes earned him harsh criticism. Marcelin Pellet, who was destined for a diplomatic career, seems to have been more measured in his 1869 review. Alfred's older brother, Paul, who after his younger brother's death became the most ardent defender of his memory and work, nevertheless seized this opportunity to respond precisely to the critic and guide him toward greater accuracy.

More than a response, this text appears as a brilliant exposition, a long dissertation, a manifesto on Musset's theatre. By claiming his brother's legacy, by establishing a hierarchy between the different genres of theatre, by definitively banishing tragedy and verse drama, Paul de Musset places his late brother at the pinnacle of 19th-century theatrical creation.