Robert Brasillach (1909.1945)

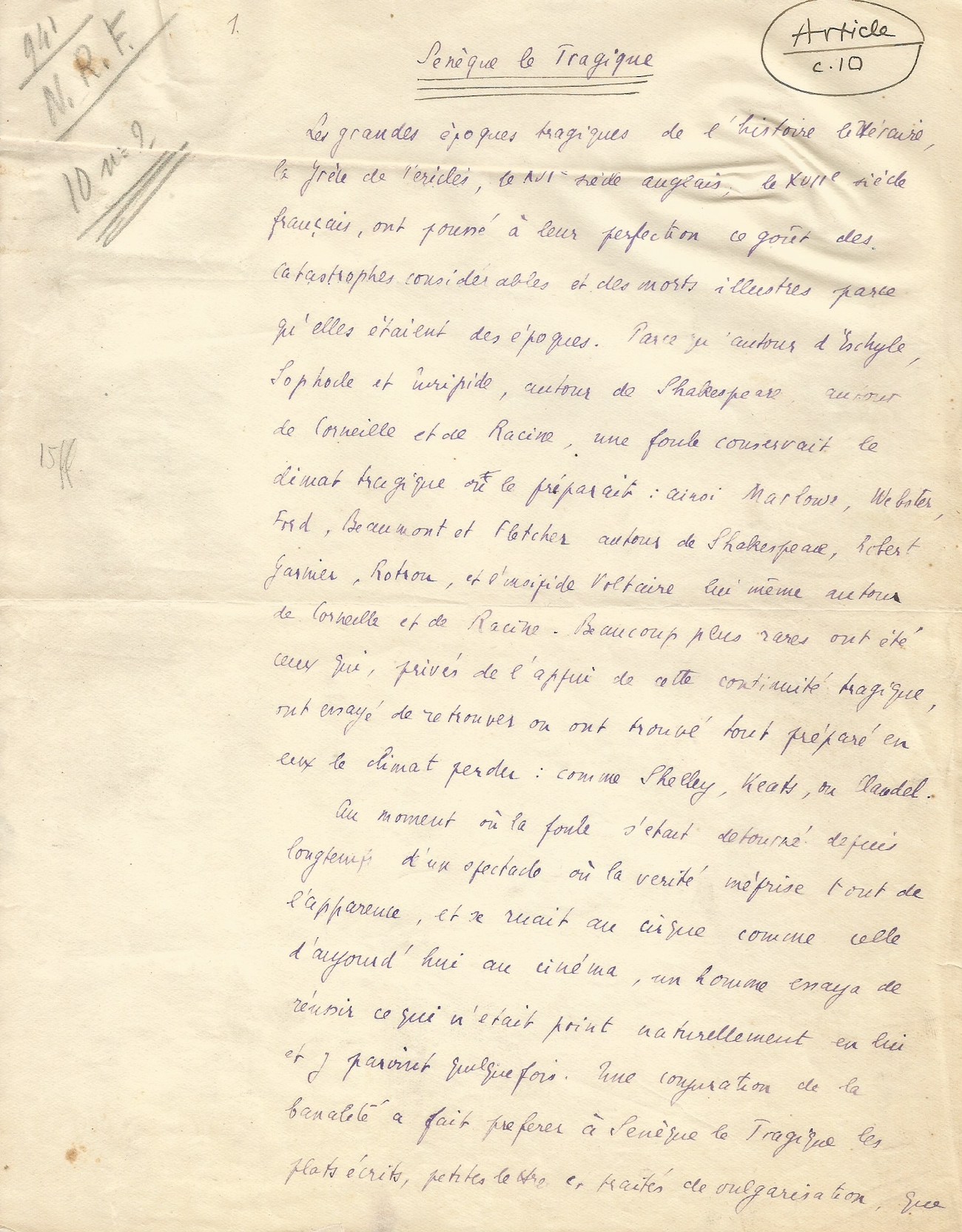

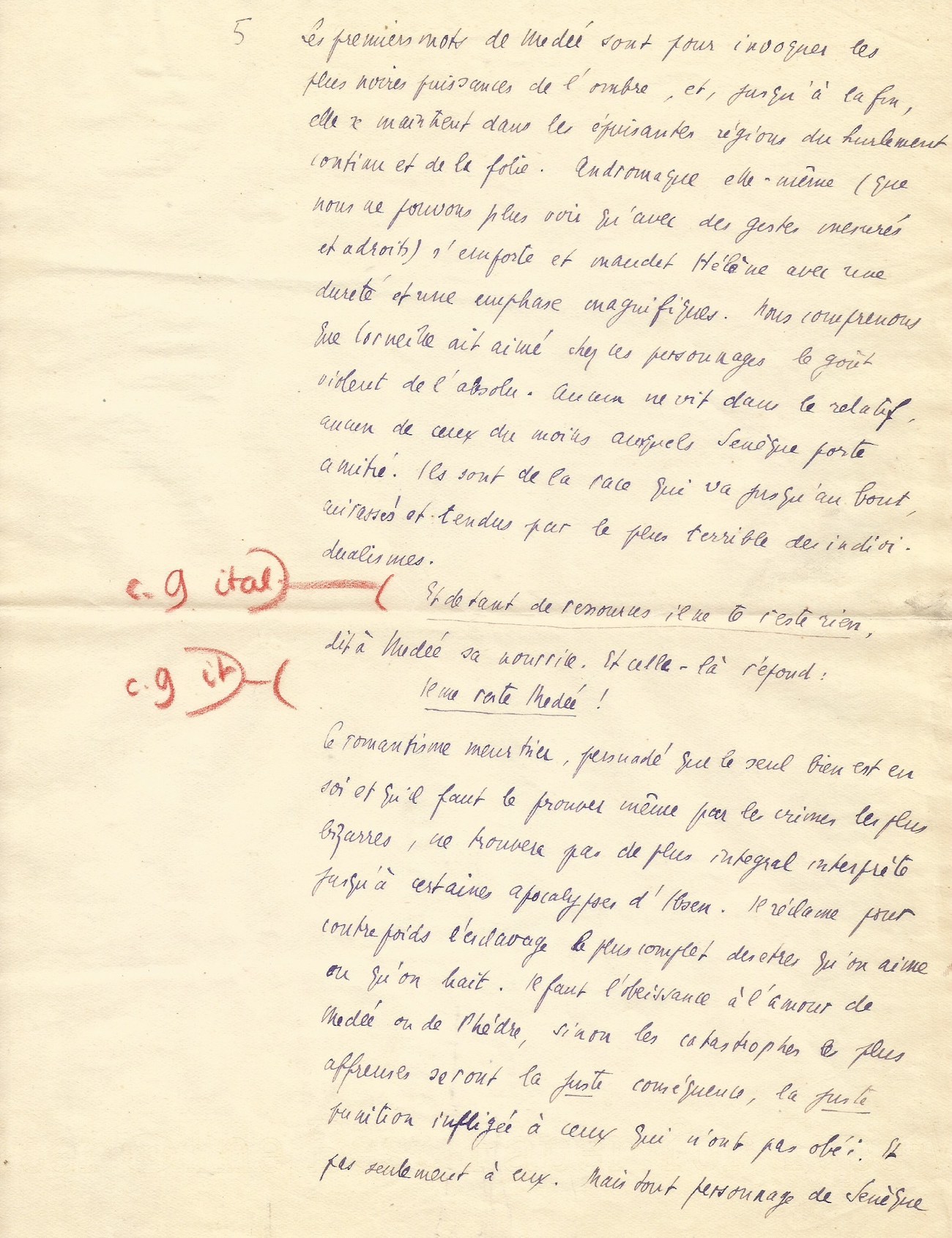

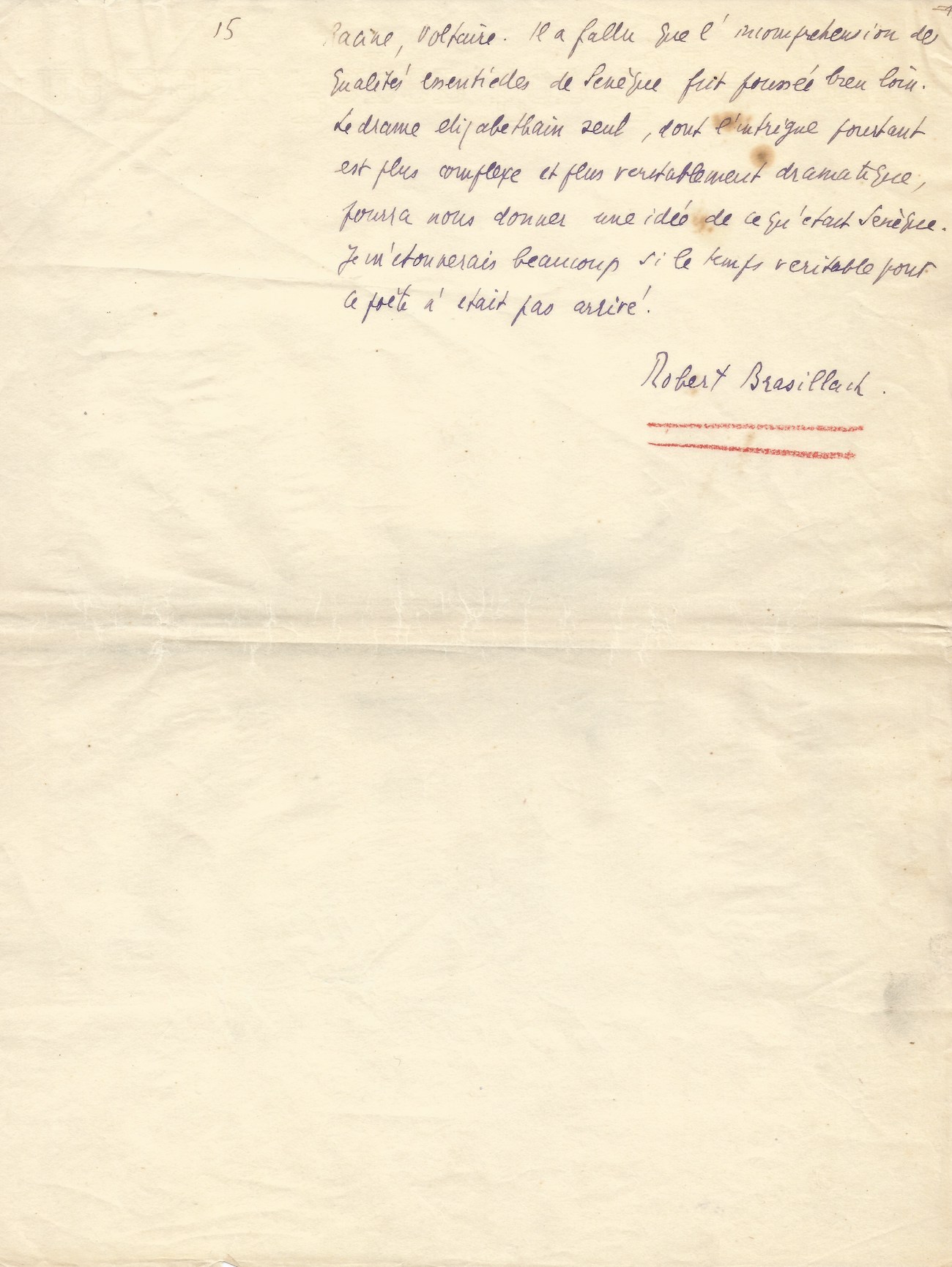

Autograph manuscript signed – Seneca the tragic.

Fifteen pages, large quarto, in violet ink. No place or date (1931)

"I would be very surprised if the true time for this poet had not yet arrived."

A beautiful manuscript by Brasillach testifying to his admiration for Seneca and his awareness of nature. This manuscript was published by the Nouvelle Revue Française in 1931.

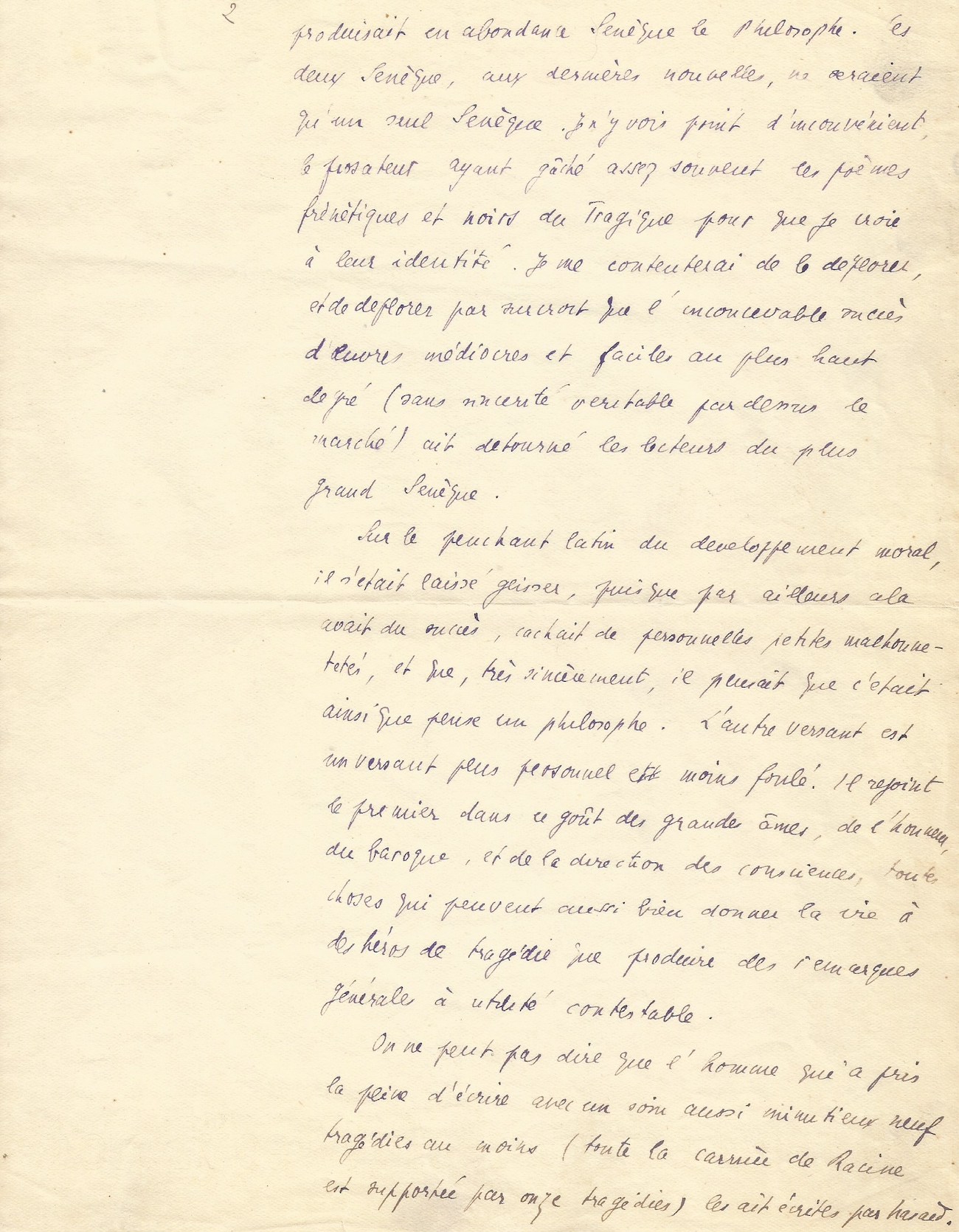

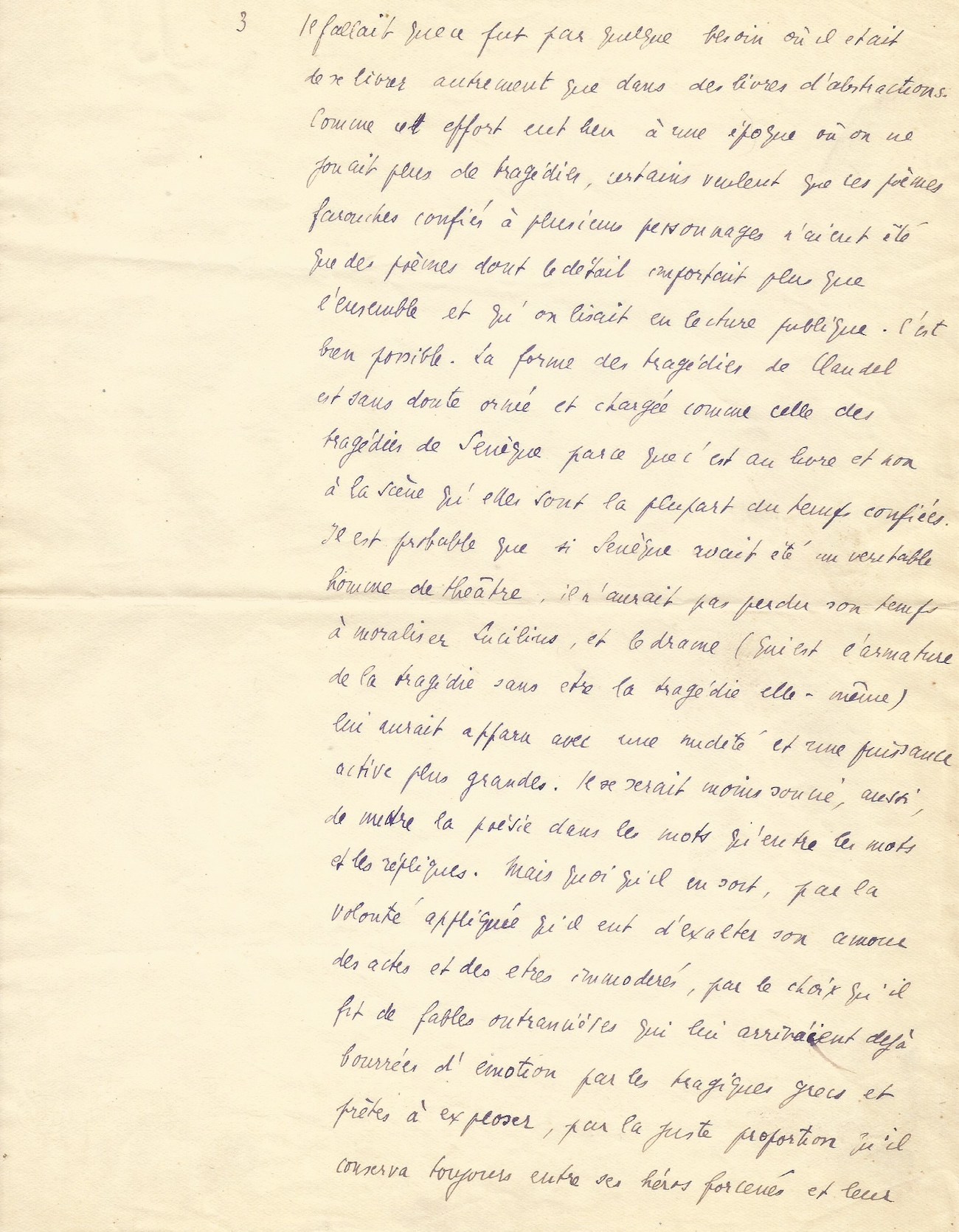

“ Seneca the Tragedian. The great tragic periods of literary history—Periclean Greece, 16th-century England, 17th-century France—brought this taste for momentous catastrophes and illustrious deaths to their perfection because they were distinct periods. Because around Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, around Shakespeare, around Corneille and Racine, a multitude of writers preserved and cultivated the tragic atmosphere: such as Marlowe, Beaumont, and Fletcher around Shakespeare, Robert Garnier, and even the insipid Voltaire himself around Corneille and Racine . Much rarer were those who, deprived of the support of this tragic continuity, tried to rediscover or found the lost atmosphere already prepared within themselves: like Shelley, Kets, or Claudel.” At a time when the crowds had long since turned away from a spectacle where truth scorns all appearances, and flocked to the circus as today's crowds flock to the cinema, a man tried to achieve what was not naturally within him, and sometimes succeeded. A conspiracy of banality led people to prefer the bland writings—little letters in popular treatises—that Seneca the philosopher produced in abundance to the tragic Seneca. The two Senecas, according to the latest news, are but one Seneca… having spoiled the frenetic and dark poems of the Tragic so often that I believe in their identity. I will simply lament this, and further lament that the inconceivable success of mediocre and utterly facile works has diverted readers from the greatest Seneca. He had allowed himself to drift towards the Latin approach to moral development, since it was successful elsewhere, concealed some minor personal dishonesty, and because (…) he thought that this was how a philosopher thinks. The other side is more personal and less trodden. It joins the first in its taste for great souls, the honor of the Baroque, and the guidance of consciences—all things that can give life to tragic heroes as well as produce general observations…. One cannot say that the man who took the trouble to write at least nine tragedies with such meticulous care (Racine's entire career is supported by eleven tragedies) wrote them by chance. (…) It must have been out of some need he had to express himself in a way other than through books of abstractions. Because this endeavor took place at a time when tragedies were no longer performed, some believe that these fierce poems, entrusted to several characters, were simply poems in which the detail mattered more than the whole, and which were read aloud in public. The form of Claudel's tragedies is undoubtedly as ornate and elaborate as Seneca's because they are most often entrusted to the book, not the stage. It is likely that if Seneca had been a true man of the theater, he would not have wasted his time moralizing about Lucilius, and drama (which is the framework of tragedy without being tragedy itself) would have appeared to him with greater nakedness and active power. By the applied will that he had to exalt his announcement of immoderate acts and beings, by the choice that he made of outrageous fables which came to him already full of emotion from the Greek tragedians and ready to explode, by the right proportion that he always maintained between his frenzied heroes and their language of several degrees more frenzied, he found himself having seized the tragic spirit several times and thus being its only representative of value between Euripides and the 16th century.

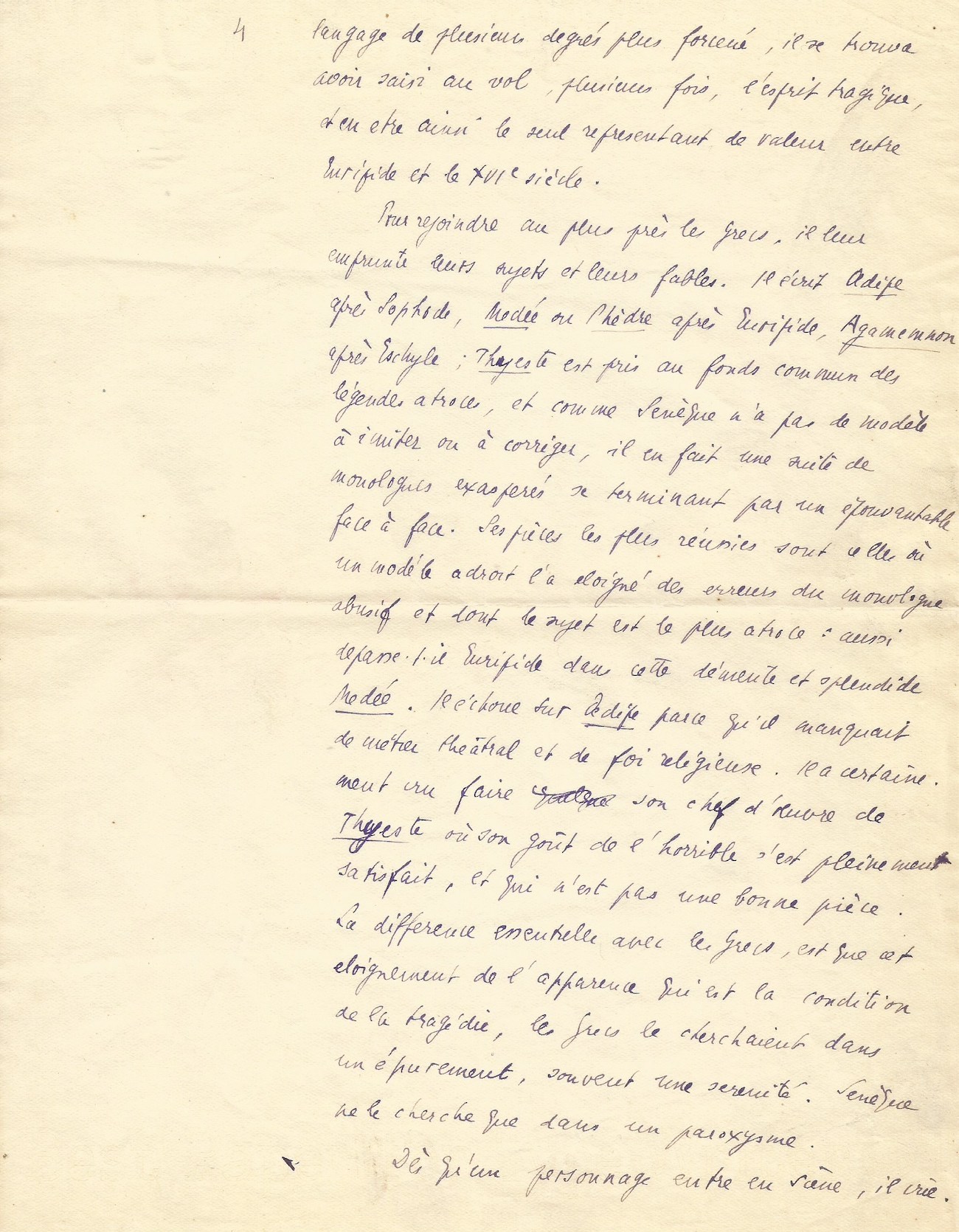

To stay as close as possible to the Greeks, he borrowed their subjects and fables. He wrote Oedipus after Sophocles, Medea and Phaedra after Euripides, Agamemnon after Aeschylus, Thyestes was drawn from the common wellspring of legends. Since Seneca had no model to imitate or correct, he crafted it into a series of exasperated monologues culminating in a horrifying confrontation. His most successful plays are those where a skillful model steered him away from the pitfalls of excessive monologue and whose subject matter is the most atrocious: thus, he surpasses Euripides in this demented and splendid Medea . He failed with Oedipus because he lacked theatrical skill and religious faith. He certainly believed he had created his masterpiece with Thyestes , where his taste for the horrific was fully indulged, but which is not a good play. The essential difference with the Greeks is that this distancing from appearances, which is the condition of tragedy, was sought by the Greeks in a purification, often a serenity. Seneca seeks it only in a paroxysm. As soon as a character enters the stage, they scream. Medea's first words are to invoke the darkest powers of shadow, and she remains in the exhausting realms of continuous howling and madness. Andromache herself (…) flies into a rage and curses Helen with magnificent harshness and emphasis. We understand why Corneille admired in these characters the violent taste for the absolute. None of them lives in the relative, none at least of those with whom Seneca feels a kinship. They belong to the breed that goes to the extreme, armored and taut with the most terrible of individualisms. (…) This murderous romanticism, which holds that the only good lies within oneself and that this must be proven even by the most bizarre crimes, will find no more complete interpreter, even in the face of certain apocalypses…. It demands, as a counterweight, the most complete enslavement of those one loves or hates. Obedience to the love of Medea or Phaedra is required, otherwise the most dreadful catastrophes will be the just consequence, the just punishment inflicted upon those who have not obeyed. But every character in Seneca (p. 6) is like the God who punishes to the third and fourth generation. None wants to die alone. (…) No one understood the dictatorship of passion better than Seneca. Should we still be surprised that he had Nero as a pupil? (…) To their own kingship, they then furiously hurl themselves to the other extreme and demand servitude with a voluptuous and noisy humility. With what tenderness, what languid sensuality, Phaedra rejects the name of mother: “The name of mother is too proud and too powerful; a humbler name suits our feelings.” (…) Seneca’s characters are intelligent. The characters of tragedy, unlike those of drama, are almost always intelligent. They know what they are and analyze it with an unspeakable joy, the joy of a clear conscience. Through this intelligence, Seneca is closer to us than Sophocles, for all the feelings we believe we invented, he perhaps already knew. The morbid, almost sadistic taste for pity was not first popularized by Russian novels. (…) To the nurse who tells her that Hercules will no longer love Iole now that she is a slave, Deianira replies in admirable verse: “Hercules’ love is only more inflamed by his misfortunes; he loves her precisely because she is deprived of her home (…) This is what, at the very moment when Seneca’s heroes were definitively becoming caricatures of Pierre Corneille or Hugo, tips the scales toward life. Amidst the excesses of a passion pushed to its limits and driven to madness, a survival of classical spirit restores to them essential lucidity. Phaedra, in the rather mediocre play that bears her name, has nothing of the intoxicating, dangerous beauty of Racine’s heroine.”

It's an easy target, one that a Freudian psychologist wouldn't want. But a very original and powerful scene saves the drama: the one where the intelligent Phaedra overcomes her unleashed desire and uses all her means to make Hippolytus yield. The scene of their declaration is so beautiful in its blend of intelligence and sensuality that Racine copied it almost exactly. Yet, if these men and women, eternally in pursuit of a frenzied ideal, can seduce modern minds, this is only one of the lesser merits of Seneca's theater. (...) The essential point is that Seneca the tragedian was a very great poet and that, like the greatest, such as Aeschylus, Shakespeare, or Baudelaire, he was bound to the world by mysterious ties and knew that the principal inspirers of a poem are the spirits of the earth. This poetic truth is found in every great tragedy; the Greeks and Racine leaned more specifically toward the gods and fate, Shakespeare toward the demons of the sensible world. This backdrop, which we will call religion, is what essentially differentiates tragedy from drama, along with the characters' detachment. It is present in Claudel. It is sometimes lacking in Corneille. Seneca did not believe in the gods. I know of no plays, except Macbeth, where the presence of nature is more visible than in his. The long monologues that open each of these tragedies first situate it in a world where it is hot or cold, where the stars shine, where the sky hides beneath black smoke, where the river flows, where the meadows tremble in the wind. (…) Macbeth can only maintain its supernatural atmosphere because there is constant talk of walking trees, hooting owls, awakening night birds, and because all the beasts of the night, all the earth's baleful powers, surround the drama and collaborate in it. (…) The Trojan Women is an admirable play entirely dominated by the high flames of Troy and the roar of ships setting sail. And these are not easy metaphors for literary criticism. (…) And in this poetic work, Seneca is served by a very beautiful language. The essential characteristics of Latin genius in the construction of these sentences are hardly found here; they are accumulations, juxtapositions rather than a chain of meaning. But this simplified syntax serves only to highlight the word that becomes the master of the sentence. Not so much the rare word as the simple but striking word, the impactful word. I would pity those who could not discern in the hideous terms with which this barbaric style is replete, in the imitation jewels, the red hues, and all the embellishments with which this savage adorns himself with such emphasis, an extraordinary, vibrant, and poetic force. (...) But this faith in the spirits of the earth, which gives Seneca's "religion" its most unsettling, most poisonous poetic power, is also combined with a taste for death and nothingness, which is truly admirable. The Greeks placed behind all their dramas the shadow of a fatalism in which Seneca no longer believes.

He allows unconscious forces to lurk around human tragedies, but he doesn't want a God or personal gods to take sides and judge. Yet, since tragedy cannot exist without religion, he puts death in place of the gods. He condemns the despair of the drama, now without escape: he closes all the doors of the cage where his terrible prisoners torment and denies them the escape to another life. (...) And this facile philosophy of nothingness, facile when it is mistaken for an original philosophy open to development, is a dramatic means of extraordinary emotion. Similarly, Hamlet's famous soliloquy is merely a series of commonplaces but takes on its full value when placed back within the drama and its atmosphere, because it is the sincere and terrified lament of a man who fears what comes next. Seneca's heroes are not afraid of what happens after death. They throw themselves into it without fear, invoking it as a liberator, as the harbor finally found. One of them, somewhere, scorns the one who does not know how to die. But it is not merely contempt for cowardice; it is contempt, almost pity, for the one who is ignorant of the greatest of blessings, who does not love death. And these two sacred elements, nature and death, merge in a religious enthusiasm for everything that is not religion. Thus Lucretius celebrated sacrifices in honor of human reason. A purely romantic doctrine, the exaltation of the individual and the exaltation of the unconscious forces of nature, comes to replace religion. From this, no doubt, arises a sometimes rudimentary faith in reason and progress, but also, above all, coupled with the superhuman pride of these heroes draped in their great crimes, a supernatural power that bypasses the gods and grants humanity. While in religions, supernatural and magical power flows from nature to humankind, necessarily passing through the gods and being irrevocably captured by them in the process, in Seneca's mysticism, magical power flows quite naturally and without intermediary from nature to humankind, which replaces the gods. Hence these incantations, which are merely the translation into ceremonial language of the well-known relationships that exist between the world and us. Hence these prophetic airs, this divinatory sense that humankind has reclaimed from the gods. The characters, those of the chorus, affirm at every moment, in a mysterious tone, the confidences that the universe has entrusted to them. " And in the years to come, the times will come when the ocean will loosen its bonds, when a vast land will spread out upon it, when the queen of the seas will then discover the New World, and it will no longer be Iceland, the last land !" How wonderful it is to discover America in the year 60! It is curious to think that this poet's fortune was as extraordinary as his talent. We know that French tragedy, this drama (…) where the chorus disappears very quickly, originated with Seneca the Tragedian. That Corneille was so admired, with all his rugged, Spanish genius, is not surprising. That Racine appreciated its intelligence and passion is very likely. But that the very technique of French tragedy, this skillful and slow progression, of clever and almost always discreet characters, should have come from this colorful, breathless, and barbaric drama—that is what I cannot understand. Nature, which holds such a vast place in Seneca's work, the taste for death—all this has disappeared from the almost purely human interplay of passions staged by Corneille, Racine, and Voltaire. The misunderstanding of Seneca's essential qualities must have been pushed to a great extent. Only Elizabethan drama, whose plot is nevertheless more complex and more truly dramatic, can give you an idea of what Seneca was like. I would be very surprised if the true time for this poet had not yet arrived. Robert Brasillach