Marcel Proust (1871.1922)

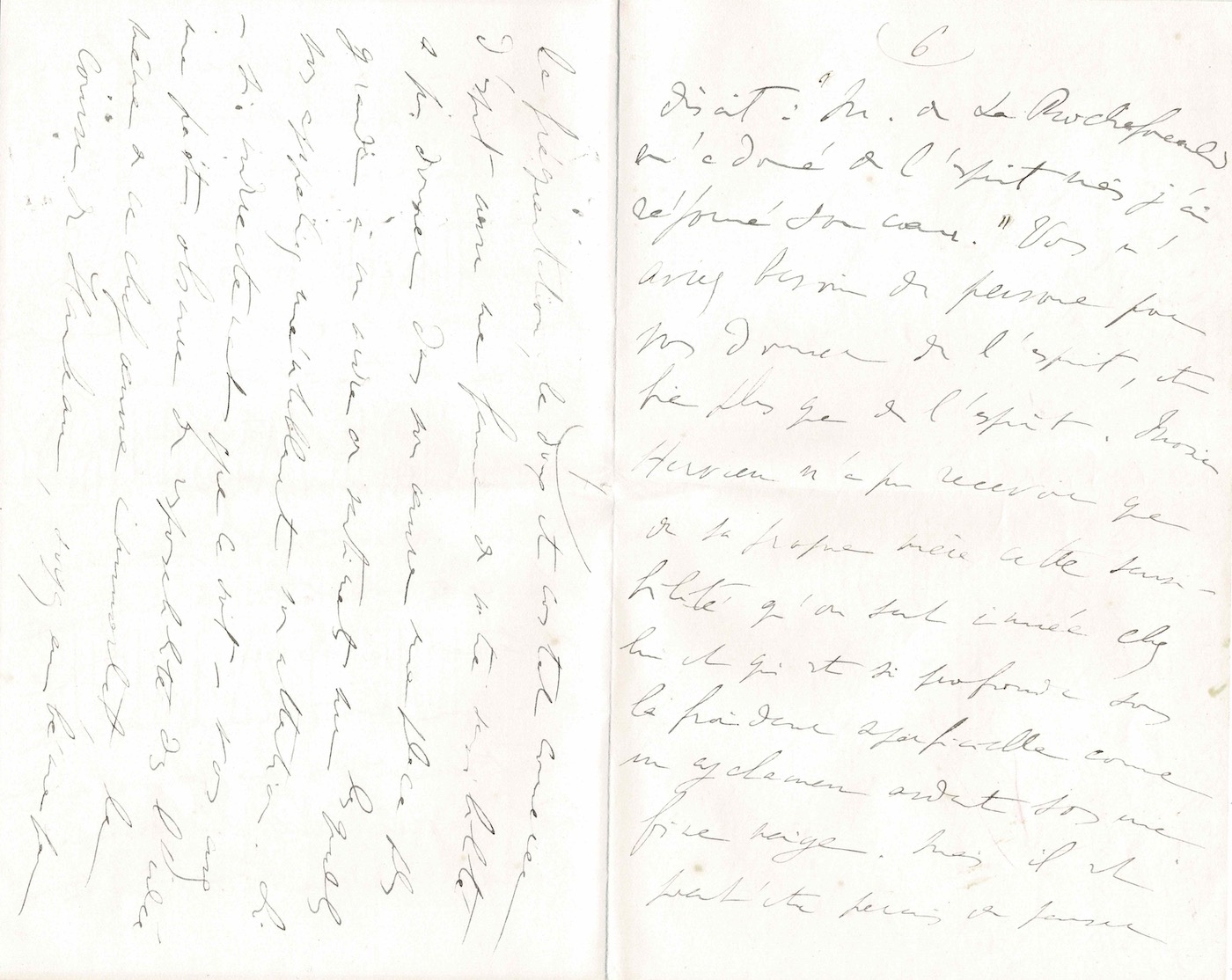

Autograph letter signed to Baroness Aimery Harty of Pierrebourg.

Eight octavo pages on mourning paper. [Versailles] Friday [October 23, 1908]

Kolb, Volume VIII, pages 249 to 251.

"And this feeling, or at least Odette's feeling for her mother, from the somewhat old pages I wrote about my own, will perhaps show you, if I ever publish them, that I am not entirely unworthy of understanding it."

An extraordinary literary letter, evoking his work in progress and the character of Odette.

_________________________________________________________________

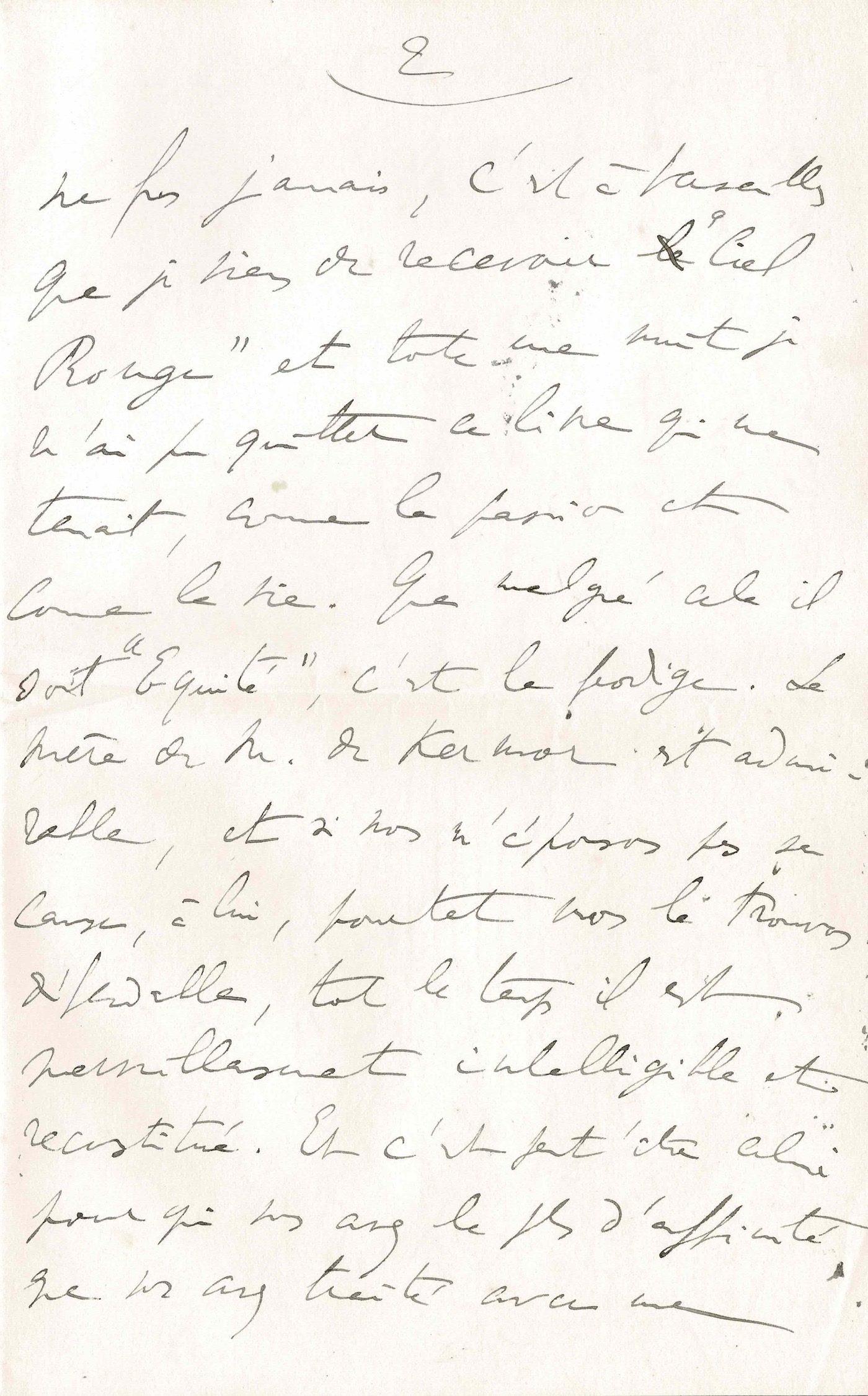

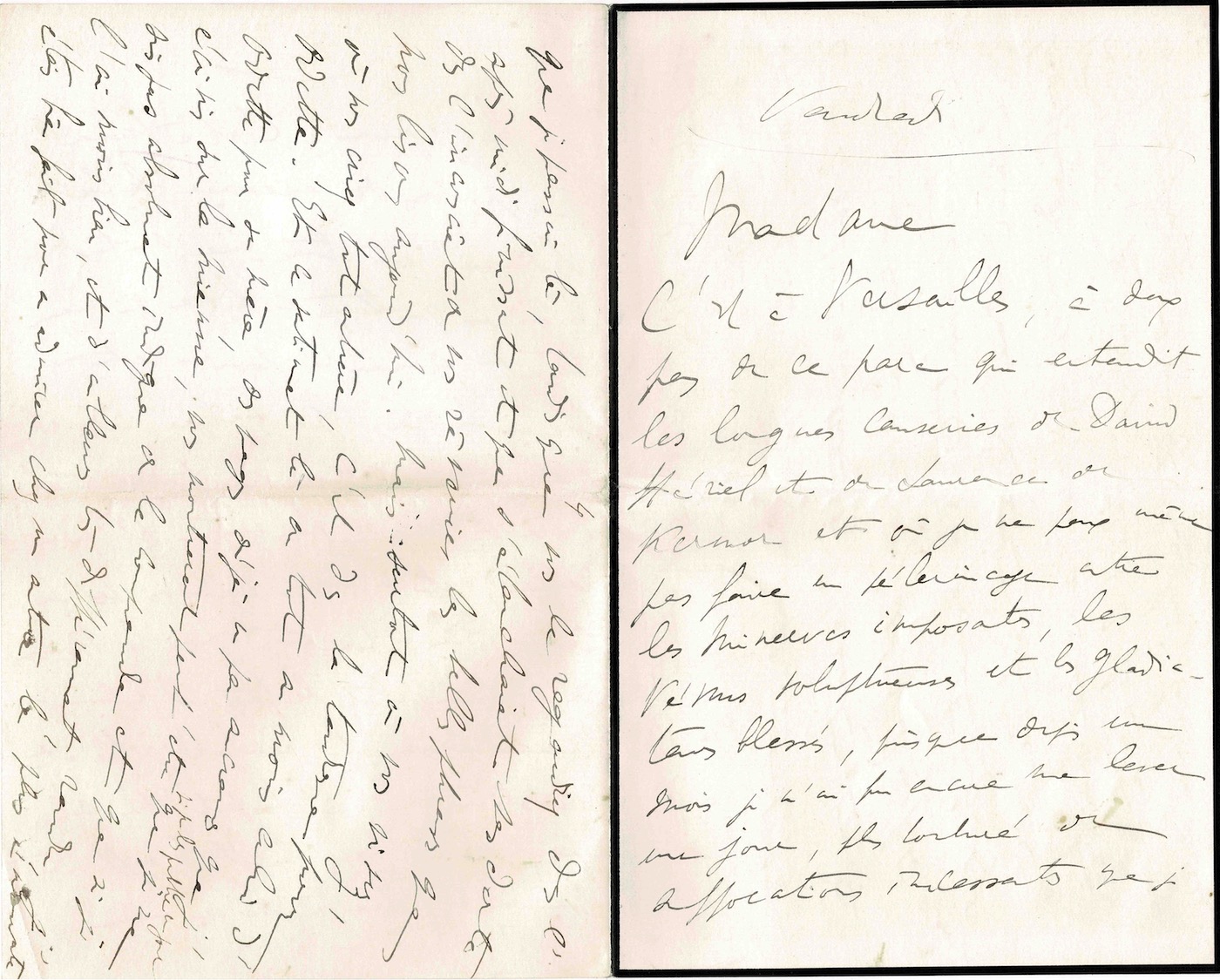

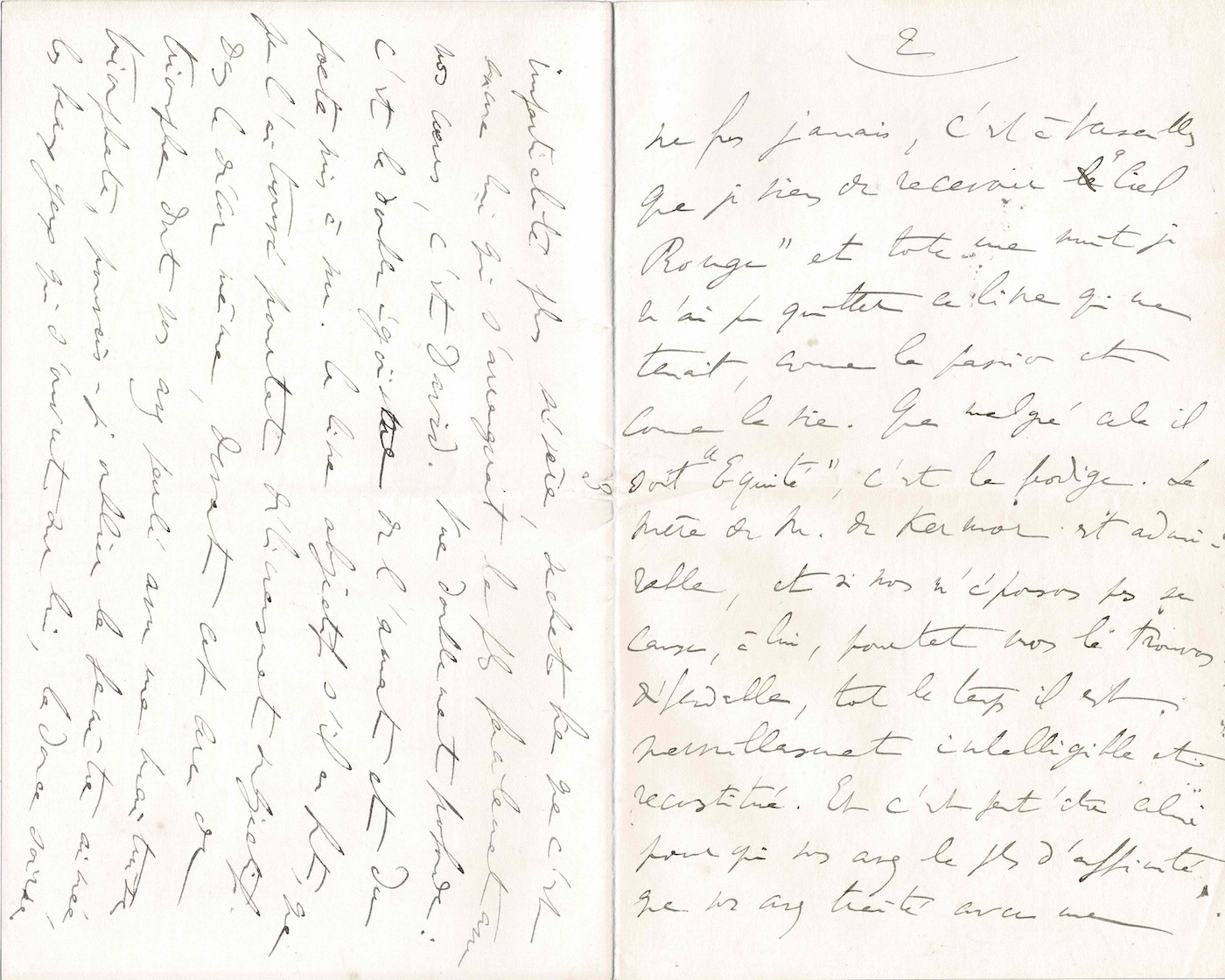

“Madam, it is in Versailles, a stone’s throw from that park which once heard the long conversations of David Hériel and Laurence de Kermot, and where I cannot even make a pilgrimage among the imposing Minervas, the voluptuous Venuses, and the wounded gladiators [characters from the recipient’s novel, *Ciel rouge*], since for a month I have not been able to get up a single day, more tormented by incessant suffocation than I have ever been, it is in Versailles that I have just received *Ciel rouge*, and all night I could not put down this book which held me captive, like passion and like life itself. That despite this it is considered “Equity” is a marvel. Monsieur de Kermor’s mother is admirable, and if we do not take up her cause, we nevertheless find his to be defensible; throughout, he is wonderfully clear and well-developed.” And perhaps it is the one with whom you feel the greatest affinity, whom you treated with the most rigorous impartiality, knowing full well that he is still the one who would most easily win our hearts, that is David. A doubly profound insight: it is the double selfishness of the lover and the poet laid bare. This book, objective if ever there was one, yet I found it delightfully subjective. In the very setting, before that Arc de Triomphe you described with such triumphant mastery, could I forget the beloved window, the beautiful eyes that gaze upon it, the sweet evening I spent there, while you watched it in the fading afternoon, and while, no doubt, in the unconscious of your reveries, the beautiful phrases we read today were being extinguished? But above all, where you truly live, where you cry out with all your heart, is in your tenderness for Odette. And this feeling, or at least Odette's feeling for her mother, from the somewhat dated pages I wrote about my own, will perhaps show you, if I ever publish them, that I am not entirely unworthy of understanding it, and that if I have rendered it less well, and indeed very differently, I was well-suited to admire its most moving expression in another. You would see that scene of "goodnight" by the bedside, quite different and how much inferior.

You're a novelist! If I could create beings and situations like you, how happy I would be!

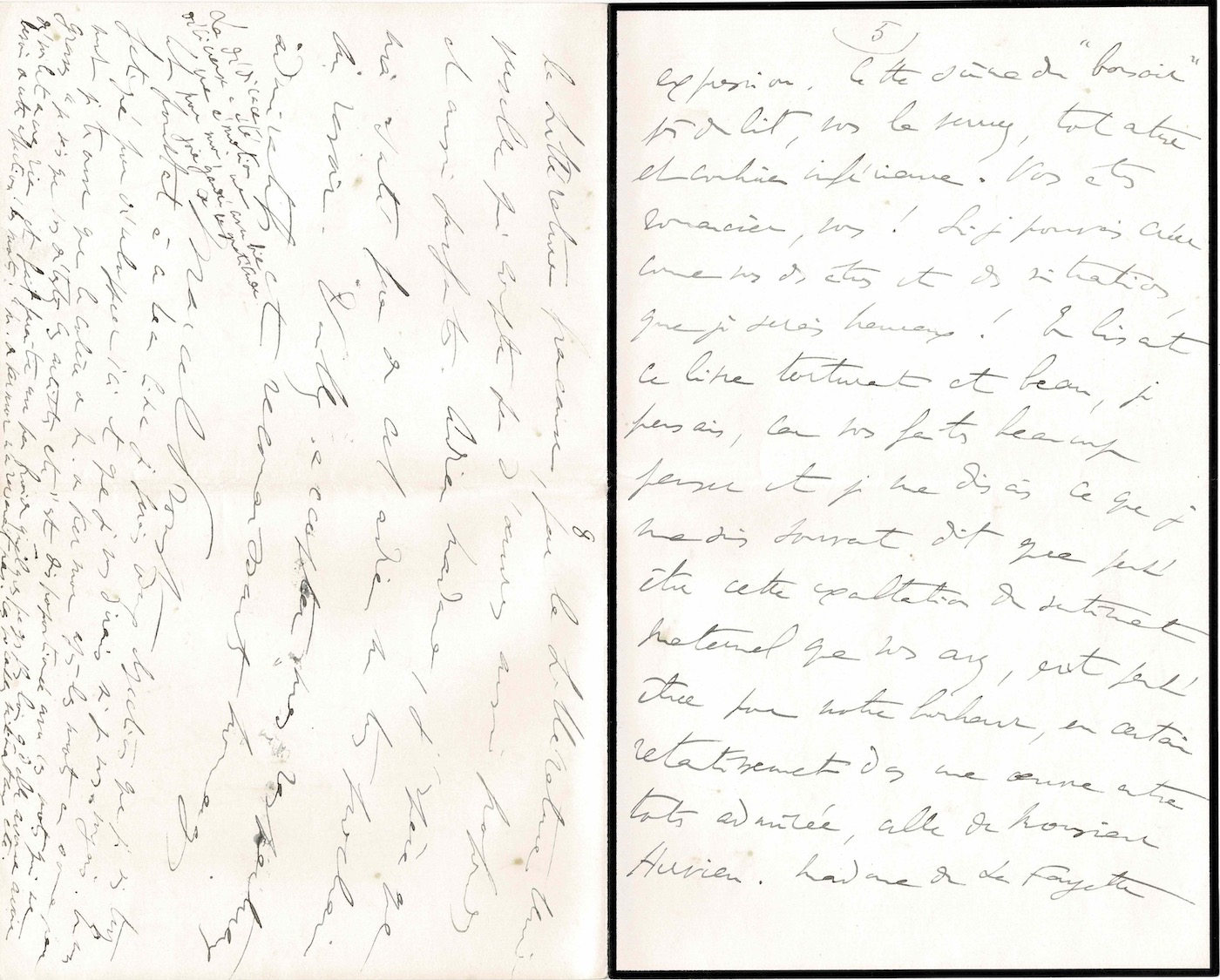

While reading this poignant and beautiful book, I thought—for you make me think a great deal, and I was thinking what I have often thought—that perhaps this exaltation of maternal feeling that you possess, perhaps fortunately, resonated in a most admired work, that of Monsieur Hervieu. Madame de La Fayette said, "Monsieur de La Rochefoucauld gave me wit, but I reformed his heart." You needed no one to give you wit, and much more than wit. Monsieur Hervieu could only have received from his own mother this sensitivity that one senses is innate in him and that is so profound beneath his superficial coldness, like a fiery cyclamen beneath a light snowfall.

But it is perhaps permissible to think that the close association, the gentle and constant intellectual exchange with a woman of your sensibility, may have given greater prominence in her work to a range of feelings to which you inevitably drew her attention. If—however indirectly—you bear some obscure share of responsibility for the very idea of this immortal masterpiece, The Torch Race, then be blessed by French Literature, by world Literature, which boasts few works as profound and as perfect.

Farewell, Madam. I hope my health will make this farewell a very soon goodbye. Please accept my respectful, admiring, and grateful regards, Marcel Proust.

And yet, I have two objections to this beautiful book, which I am too tired to elaborate on here, and which I would share with you if I saw you. In short, I find that Monsieur de Kermor's anger after the rather trivial words, "I know you detest artists, etc.," is disproportionate to these words, which reveal nothing further, and makes the words a few pages later, when she confesses to needing this affection, seem a little cold: "Monsieur de Kermor couldn't believe it. These sentimental words, etc." The delightful dedication was a moving experience for me, a joy I cherish with deep gratitude.