Marcel Proust (1871.1922)

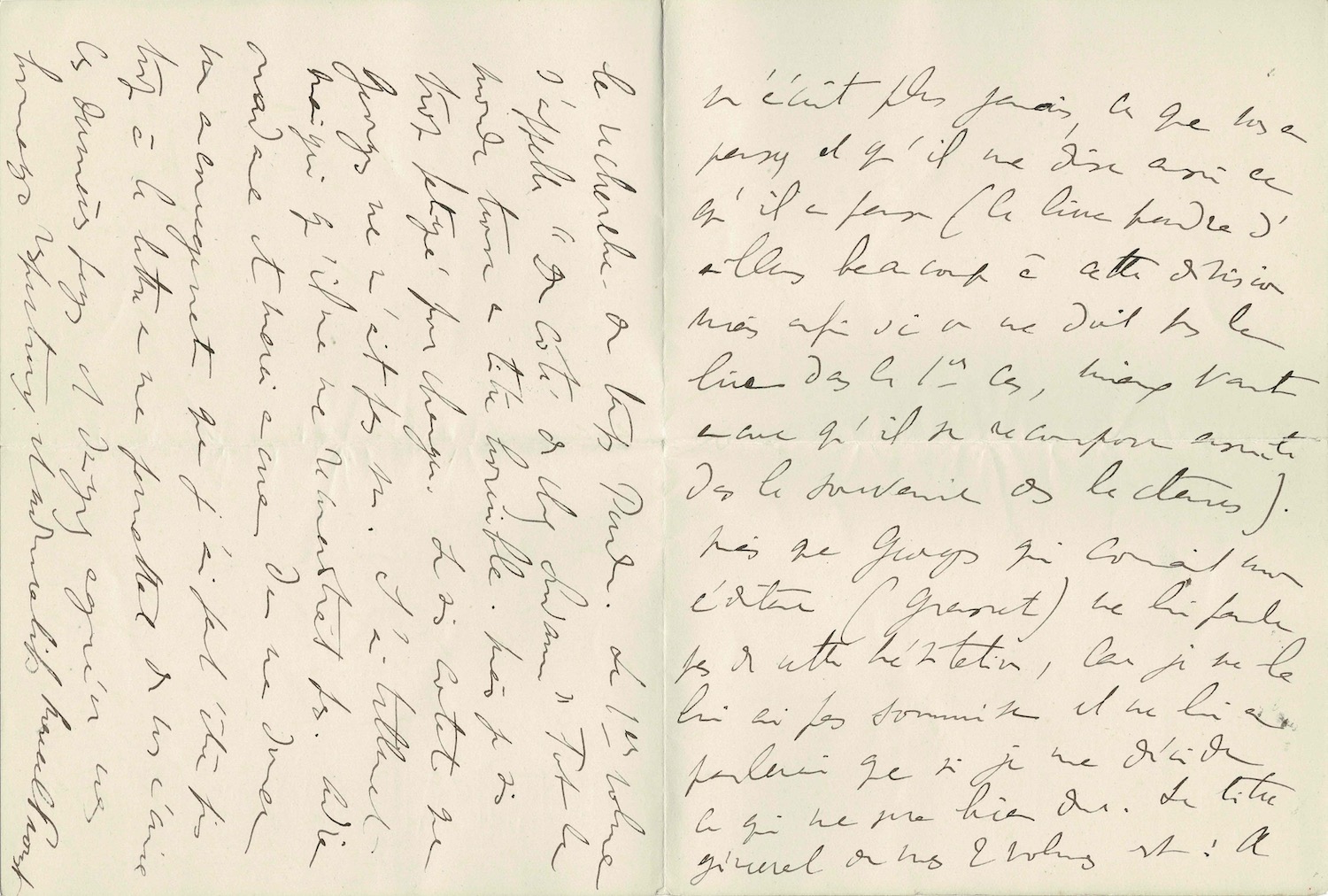

Autographed letter signed to Baroness Aimery Harty de Pierrebourg.

Seven pages in-8°. No place [shortly before July 10, 1913]

Kolb, Volume XII, pages 225 to 228.

"The overall title of my two volumes is: In Search of Lost Time. The first volume is called 'Swann's Way.' Everyone thinks that title is awful. But I'm too tired to change it."

An exceptional and long autograph letter signed by Marcel Proust to his friend Baroness Aimery Harty de Pierrebourg, a writer under the pen name Claude Ferval.

______________________________________________

In Marcel Proust's sprawling correspondence, the game of socializing occupies a prominent place; the truly literary and more intimate letters are all the more desirable.

The stepmother of Georges de Lauris, one of Marcel Proust's friends whom he met in 1903 and who served as a trusted advisor for the writing of what would become * Contre Sainte-Beuve*, Marguerite de Pierrebourg (1856-1943) was initially a painter before turning to writing. Her first novel was recognized by the French Academy, and from 1912 she became president of the Prix de la Vie Heureuse (later the Prix Fémina), thus occupying an important place in Parisian literary life. Marcel Proust frequented her salon and consulted her on literary matters.

She was notably one of the witnesses to the difficult gestation of the first volume of In Search of Lost Time. Rejected by Fasquelle, the Nouvelle Revue française, and then Ollendorff—despite the friendly recommendations of friends, foremost among them Louis de Robert—this first volume was perplexing in its subject matter and unsettling in its length. Proust finally agreed to divide it into several volumes, forcing him to rewrite certain chapters. The title was also the subject of criticism from the author's friends, particularly from his first proofreader and promoter, Louis de Robert, who found the phrase Swann's Way "inconceivable, so commonplace is it."

It was in this difficult context – both exhausted and almost fatalistic – that Proust addressed his friend, first congratulating her on a recent biography and then noting the importance of childhood memories for his correspondent, a kind of "time regained": " I hadn't imagined that Catholicism had played such a large role in your childhood, I didn't know you were so attached to the memory of processions (I say this with sympathy because I am exactly like that). Are you not familiar with Reynaldo Hahn's La Carmélite ? Mendès's libretto was weak, but the music is both of its time and timeless. "

Then, emphasizing the importance of his correspondent's advisory role (" were you not, I believe, the only person to whom I once sought advice on an edition of my pastiches? And the publishers' ill will prevented me from carrying it out ."), he humorously addresses the difficulties encountered in publishing the first volume of In Search of Lost Time :

“ For the book I am finishing, I would very much like your advice […] . My book, being nearly 1,500 pages long (and pages without a single blank space, with an enormous number of lines), had to be divided into two volumes under different titles, like people who have a tapestry too big for their apartment and are forced to cut it in half. But now that I have corrected the proofs of the first volume, which has about 680 to 700 pages, I am being told that no one will ever read a book of this length .”

He claims not to care about success but rather about being read, admitting he is ready to accept further changes if necessary:

« No consideration of success could (and I have proven this through my struggle with my publishers) persuade me to change the structure of this work (already different from what I intended). But if it's not a question of success, but of being read, if my work truly must remain unknown, then I might resign myself to either a first volume of 500 pages, or three smaller volumes of 200 pages each, sold together in a sort of slipcase. If you have any advice on this, without bothering to reply, please tell Georges, who never writes to me anymore, what you think, and ask him to tell me what he thinks as well (the book will lose a great deal with this division, but if it's not to be read in the first case, it's better that it be pieced together later in the memory of readers). »

Discretion is requested from his correspondent with Grasset, the publisher of the volume (self-published), and then he makes this confession, which is quite moving in that it reveals his fatigue and even dejection: " The general title of my two volumes is: In Search of Lost Time. The first volume is called 'Swann's Way'. Everyone finds this title horrible. But I am too tired to change it. "

______________________________________________

Full text :

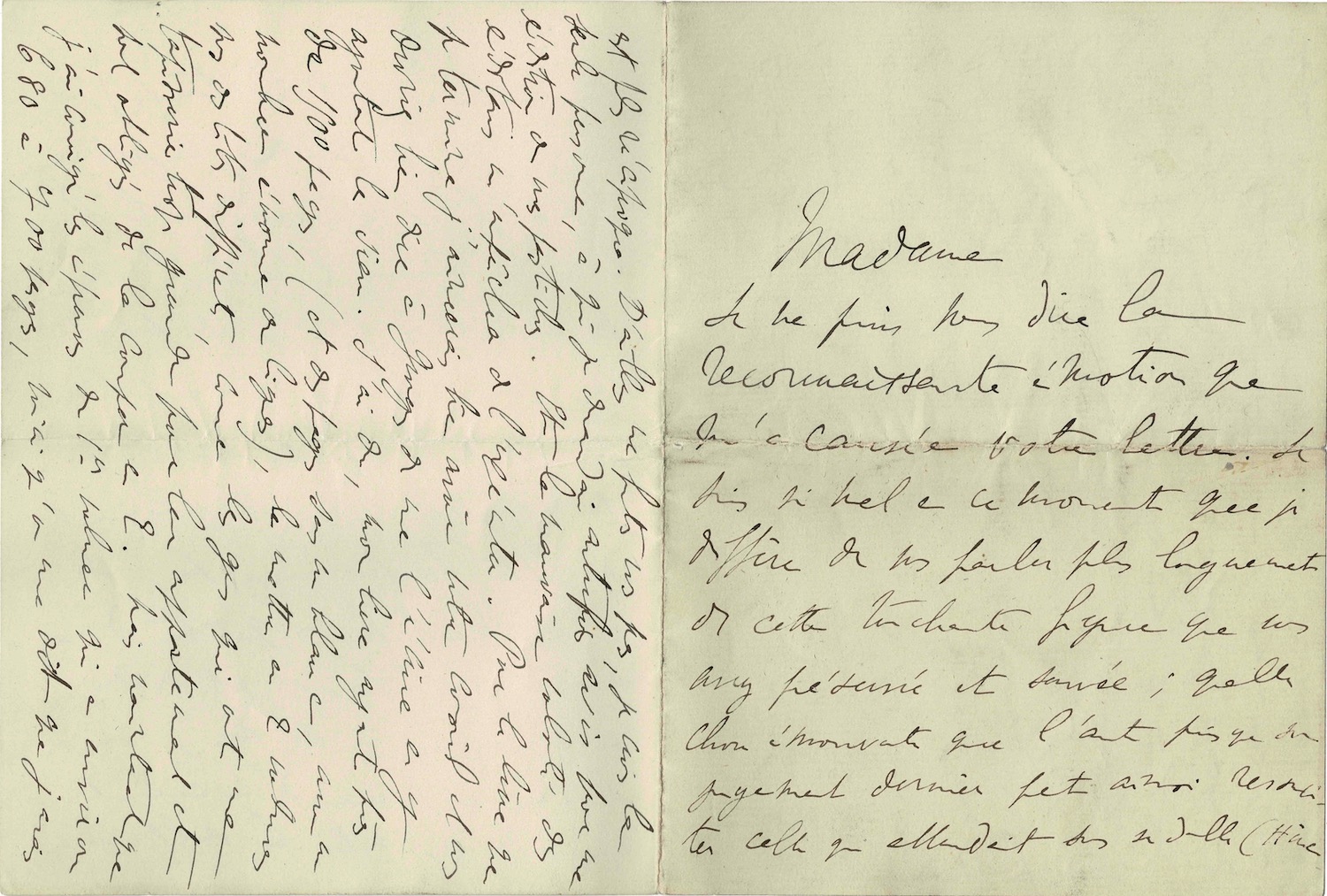

“Madam, I cannot express the grateful emotion your letter caused me. I am so unwell at the moment that I am postponing speaking to you at greater length about this touching figure you have preserved and saved; what a moving thing art is, since its final judgment can thus resurrect her who waited beneath her tombstone (“Hinc Surrectura,” says the tomb), and since in its mysterious alchemy it knows how to bring forth, one through the other, the soul of the model and the soul of the painter, of the two Friends who have crossed the distance of centuries to be reunited. Who can say which took the first step, the one who inspired her in search of a deserving and scorned dead woman into whom to transfuse her life, or the soul yearning for a new incarnation who came to solicit her, to haunt her dream, and to tempt her brush?”

I hadn't imagined that Catholicism had played such a large role in your childhood; I didn't know you were so attached to the memory of processions (I say this with sympathy because I am exactly the same). Are you not familiar with Reynaldo Hahn's play, *La Carmélite* ? Mendès's libretto was weak, but the music is both of its time and timeless. You see, I'm bringing up your book almost in spite of myself. I only wanted to tell you that if what I think truly concerns you at all, which makes me very proud, I assure you that the feeling is mutual. Besides, weren't you, I believe, the only person I once consulted about publishing my pastiches? And the publishers' reluctance prevented me from doing so.

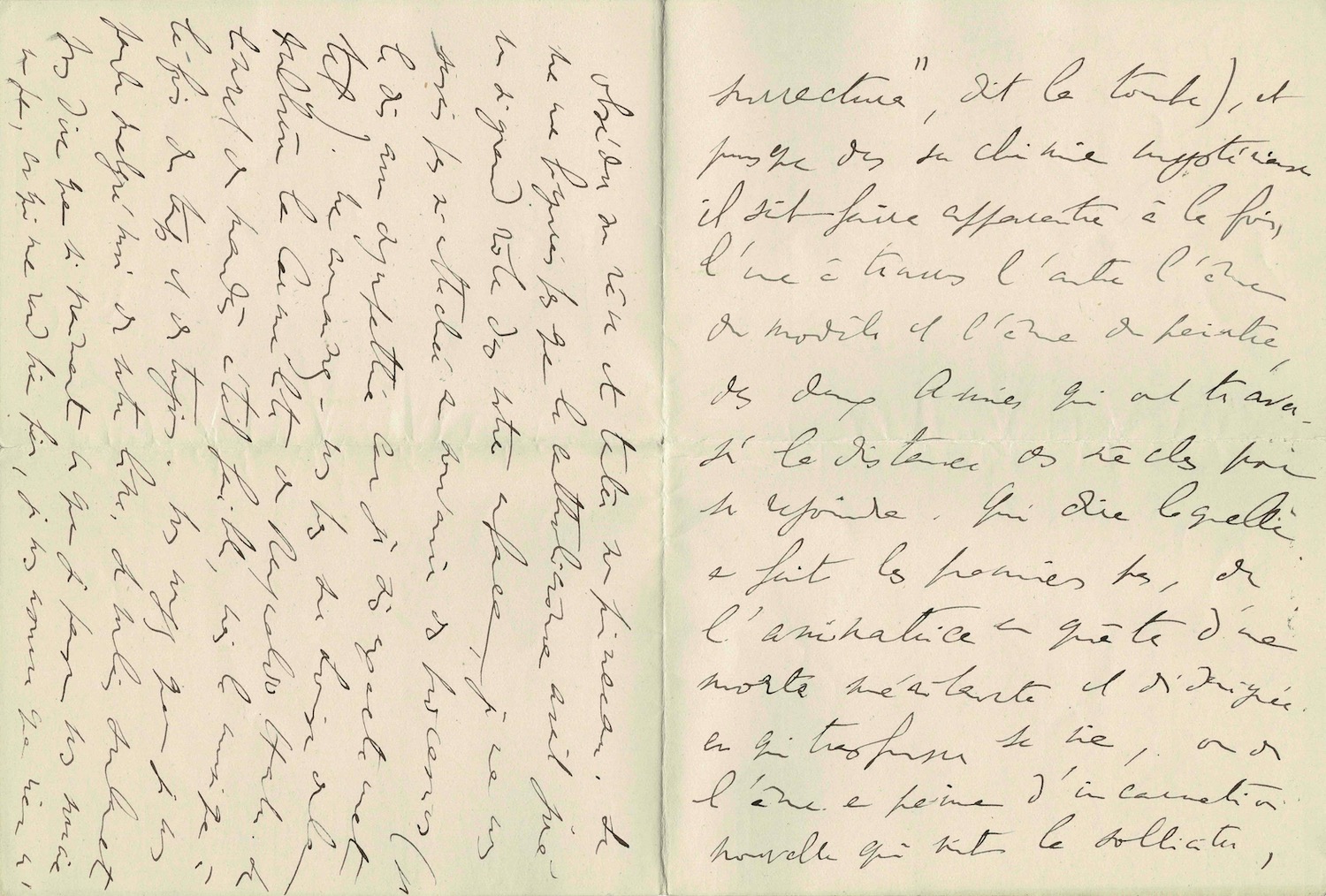

For the book I'm finishing, I'd really appreciate your advice , and you should tell Georges to write it down for me , adding his own. My book, being nearly 1,500 pages long (and pages without a single blank space, with an enormous number of lines), had to be divided into two volumes under different titles, like people who have a tapestry too big for their apartment and are forced to cut it in half. But now that I've proofread the first volume, which is about 680 to 700 pages, I'm being told that no one will ever read a book that long .

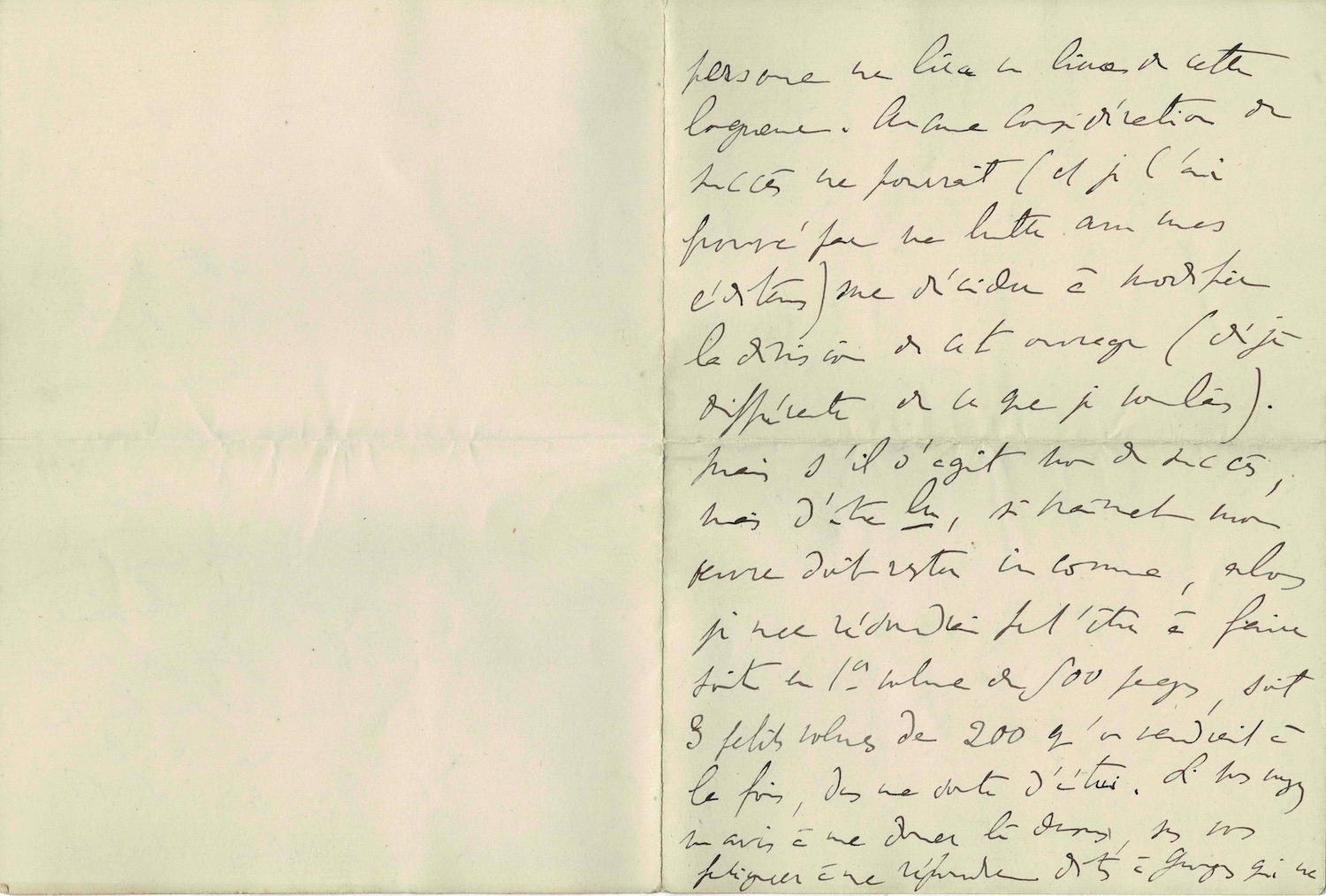

No consideration of success could (and I have proven this through my struggle with my publishers) persuade me to change the structure of this work (already different from what I intended). But if the goal is not success, but simply to be read, if my work truly must remain unknown , then I might resign myself to either publishing a first volume of 500 pages, or three smaller volumes of 200 pages each, sold together in a sort of slipcase. If you have any advice on this, without bothering to reply, please tell Georges, who never writes to me anymore, what you think, and ask him to tell me what he thinks as well (the book will lose a great deal with this division, but if it's not to be read in the first case, it's better that it be reconstructed later in the memories of readers).

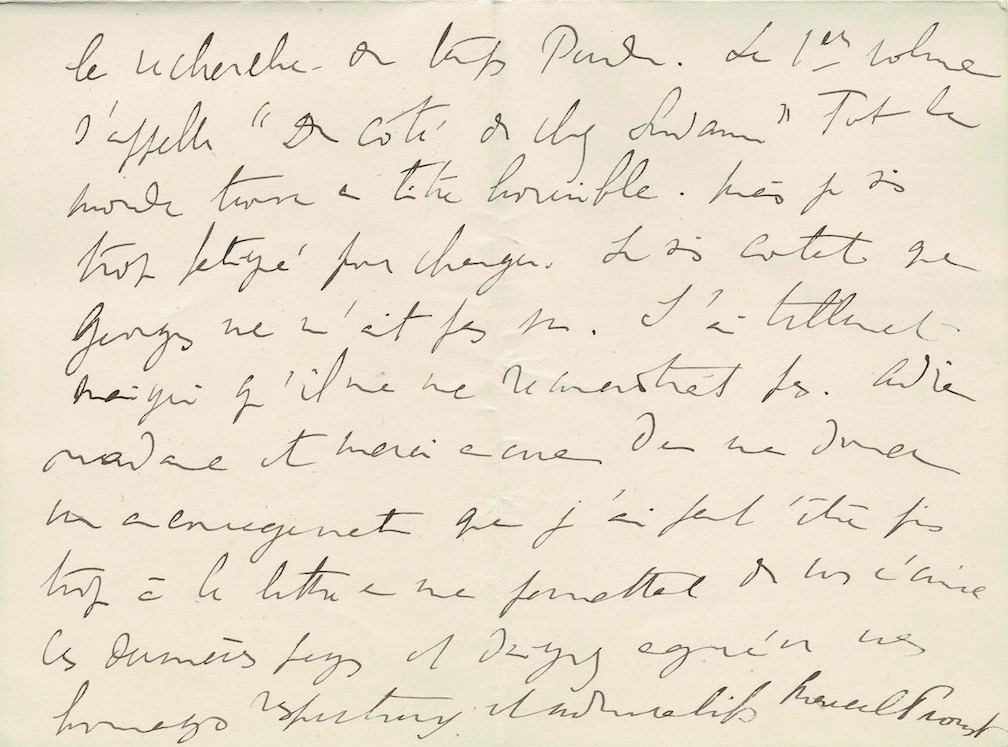

But Georges, who knows my publisher (Grasset), shouldn't mention this hesitation to him, because I haven't discussed it with him and will only do so if I make up my mind, which will be very difficult. The overall title of my two volumes is: In Search of Lost Time. The first volume is called "Swann's Way." Everyone thinks that title is awful. But I'm too tired to change it.

I'm glad Georges didn't see me. I've lost so much weight he wouldn't recognize me. Farewell, Madame, and thank you again for your encouragement, which I perhaps took too literally, by allowing me to write these last pages to you. Please accept my respectful and admiring regards. Marcel Proust