Marcel Proust (1871.1922)

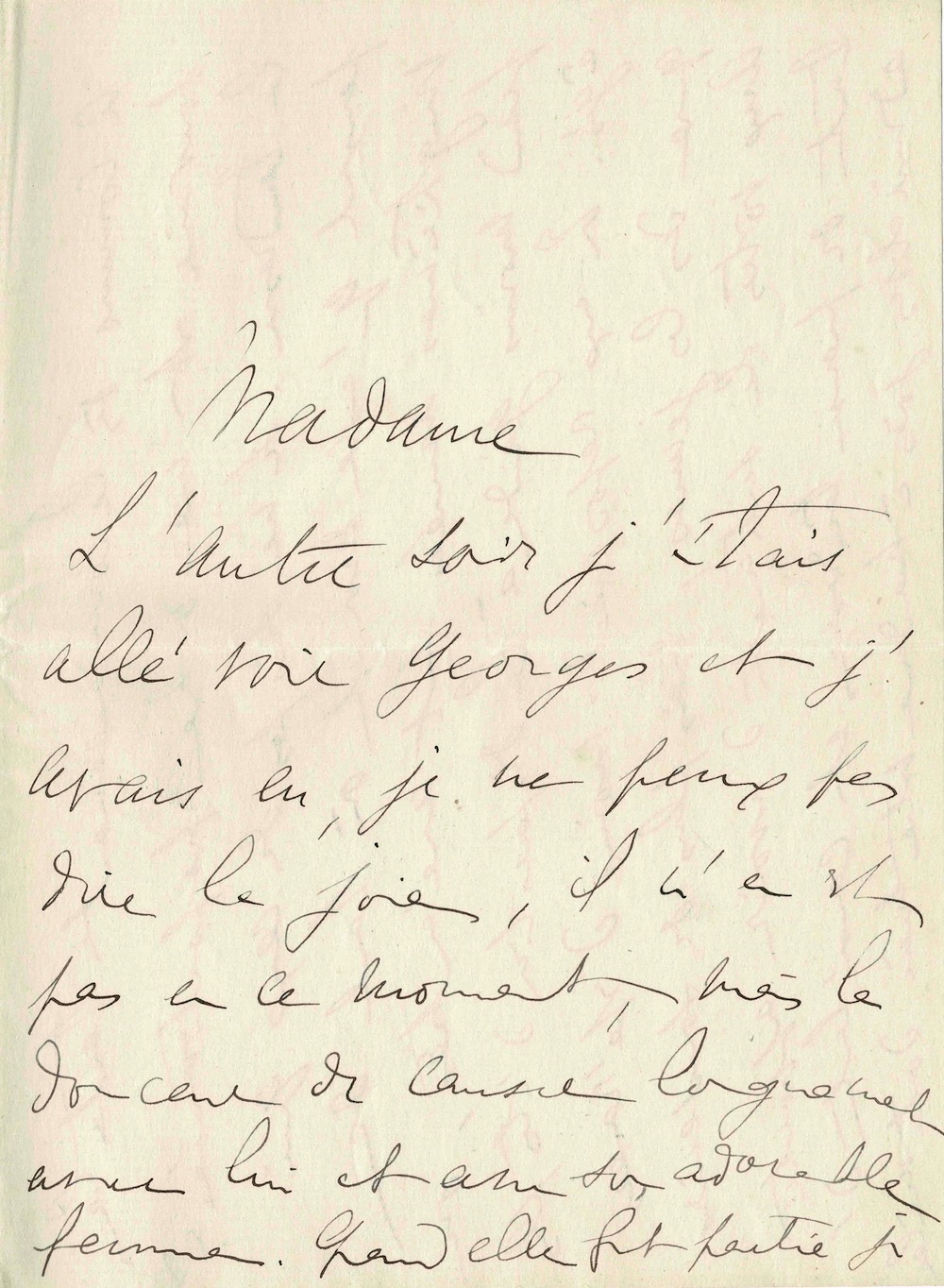

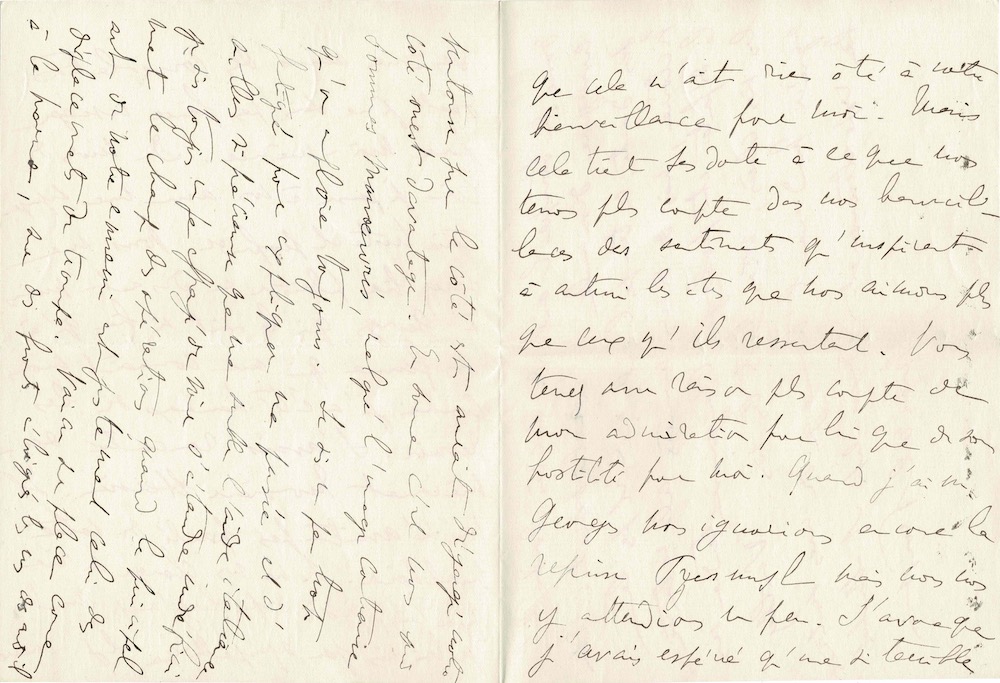

Autograph letter signed to Baroness Aimery Harty of Pierrebourg.

Eight pages in-8°. No place [shortly after June 3, 1915]

Kolb, Volume XIV, pages 143 to 145.

"I know that we regret until the end those we knew from the beginning, so much so that memory is a shadow proportionate to tenderness.". »

In the midst of the First World War, Proust sent his correspondent a magnificent letter of condolence following the death of his mother. Moved to see young French souls dying at the front, he confessed frankly that grief was an integral part of his being: "so much so that it seems to me that the daily experience I have of it could provide friendly souls with consolations that I do not know how to use for myself."

_______________________________________________

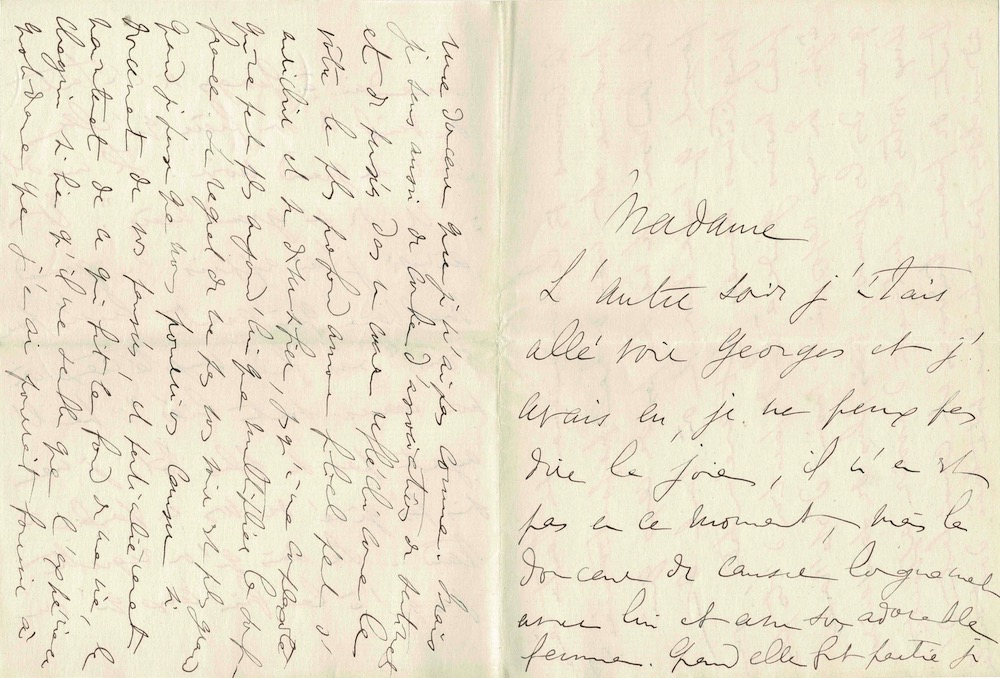

“Madam, The other evening I went to see Georges and I had, I cannot say joy—he is not experiencing that at the moment—but the pleasure of a long conversation with him and his lovely wife. When she had left, I asked Georges if she was dressed in black because of her brother's death. He said, ‘And his grandmother.’ And so I learned of this great misfortune that had broken for you ‘The mysterious threads to which our hearts are bound’ [Victor Hugo’s verse] . Not having known it sooner, I am not embarrassed to tell you of it so late. I know that one misses until the very end those one has known from the beginning, so much is the shadow of memory proportionate to the tenderness.”

I am not one of those who think that, at a time when so many twenties are vanished, we pay less attention to the passing of older people. In them rested fewer hopes than in the young, but more memories. For your family, the feeling of having brought so much pious tenderness and caused so much admiring joy to your mother must be mingled with a sweetness I have never known. But I also sense how, in a thoughtful heart like yours, the deepest filial love can be enriched and diversified by the associations of feelings and thoughts, to a complexity that today can only multiply suffering.

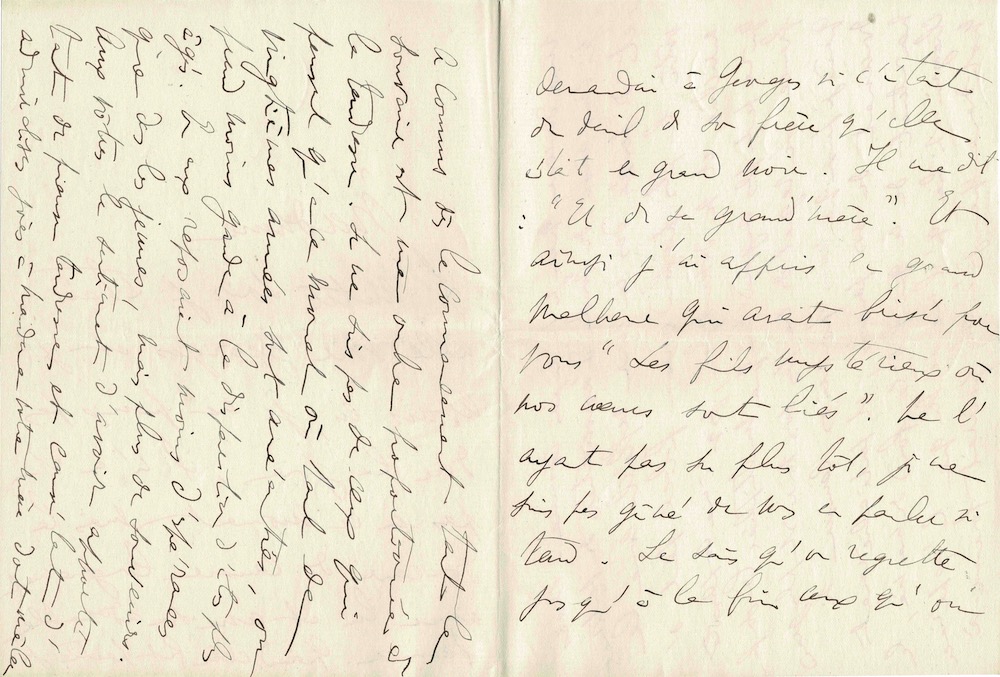

The regret of not seeing you is greater when I think that we could talk so sweetly about your thoughts, and particularly now about what formed the basis of my life, grief, so much so that it seems to me that the daily experience I have of it could provide friendly souls with consolations that I do not know how to use for myself.

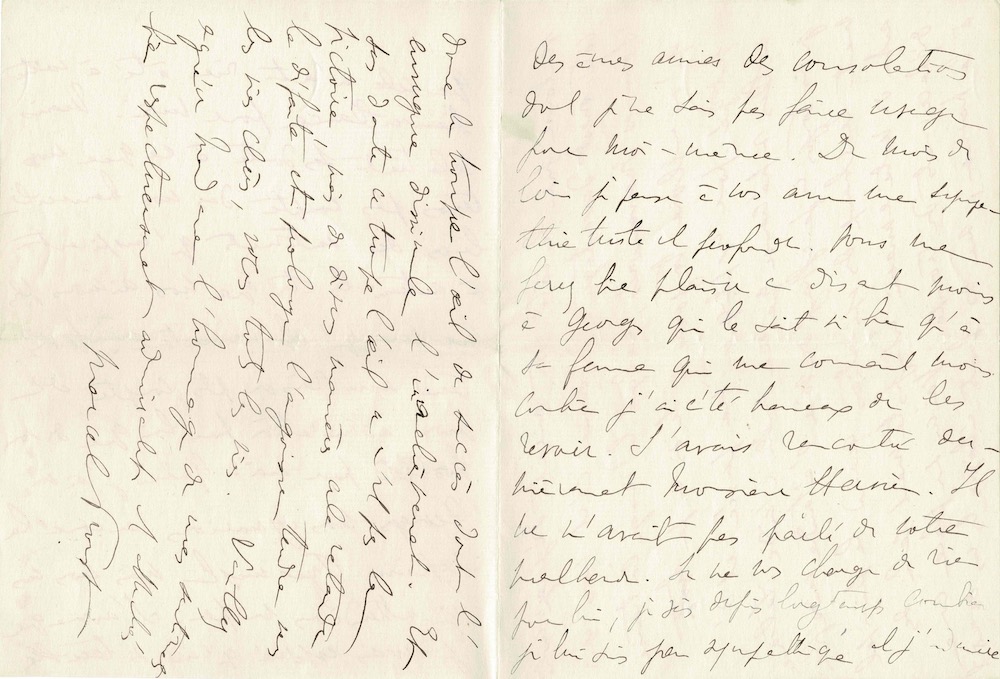

At least from afar, I think of you with a deep and sorrowful sympathy. You would do me great favor by telling Georges, who knows it so well, and his wife, who knows me less well, how happy I was to see them again. I recently met Mr. Hervieu. He didn't mention your misfortune to me. I don't burden you with anything on his behalf; I've known for a long time how little I like him, and I admire that this hasn't diminished your kindness toward me. But this is undoubtedly because, in our acts of kindness, we tend to consider more the feelings that those we love inspire in others than those they feel. You are quite right to consider my admiration for him more than his hostility toward me.

When I saw Georges, we were still unaware of the recapture of Przemyśl, but we were somewhat expecting it. I confess I had hoped that such a formidable hold on the eastern flank would have freed up our western side more. In short, it is we who are being manipulated, despite the contrary image that is always used. I am a little too tired to explain my thoughts, and besides, however valuable Italian aid may seem to me, I am still somewhat frightened to see the field of operations expand indefinitely when our enemy's principal art is precisely that of troop movements. Defeated on the spot, as at the Marne, on fronts far removed from one another, he creates the illusion of success whose scale conceals its incompleteness. And no doubt this illusion is not victory, but in various ways it delays defeat and prolongs the anguish focused on loved ones, on all lives . Please accept, Madam, the expression of my most respectful and admiring sentiments. Marcel Proust.

________________________________________________

The stepmother of Georges de Lauris, one of Marcel Proust's friends whom he met in 1903 and who served as a trusted advisor for the writing of what would become * Contre Sainte-Beuve*, Marguerite de Pierrebourg (1856-1943) was initially a painter before turning to writing. Her first novel was recognized by the French Academy, and from 1912 she became president of the Prix de la Vie Heureuse (later the Prix Fémina), thus occupying an important place in Parisian literary life. Marcel Proust frequented her salon and consulted her on literary matters. She was notably one of the witnesses to the difficult gestation of the first volume of * In Search of Lost Time*.