Lucien REBATET (1903.1972)

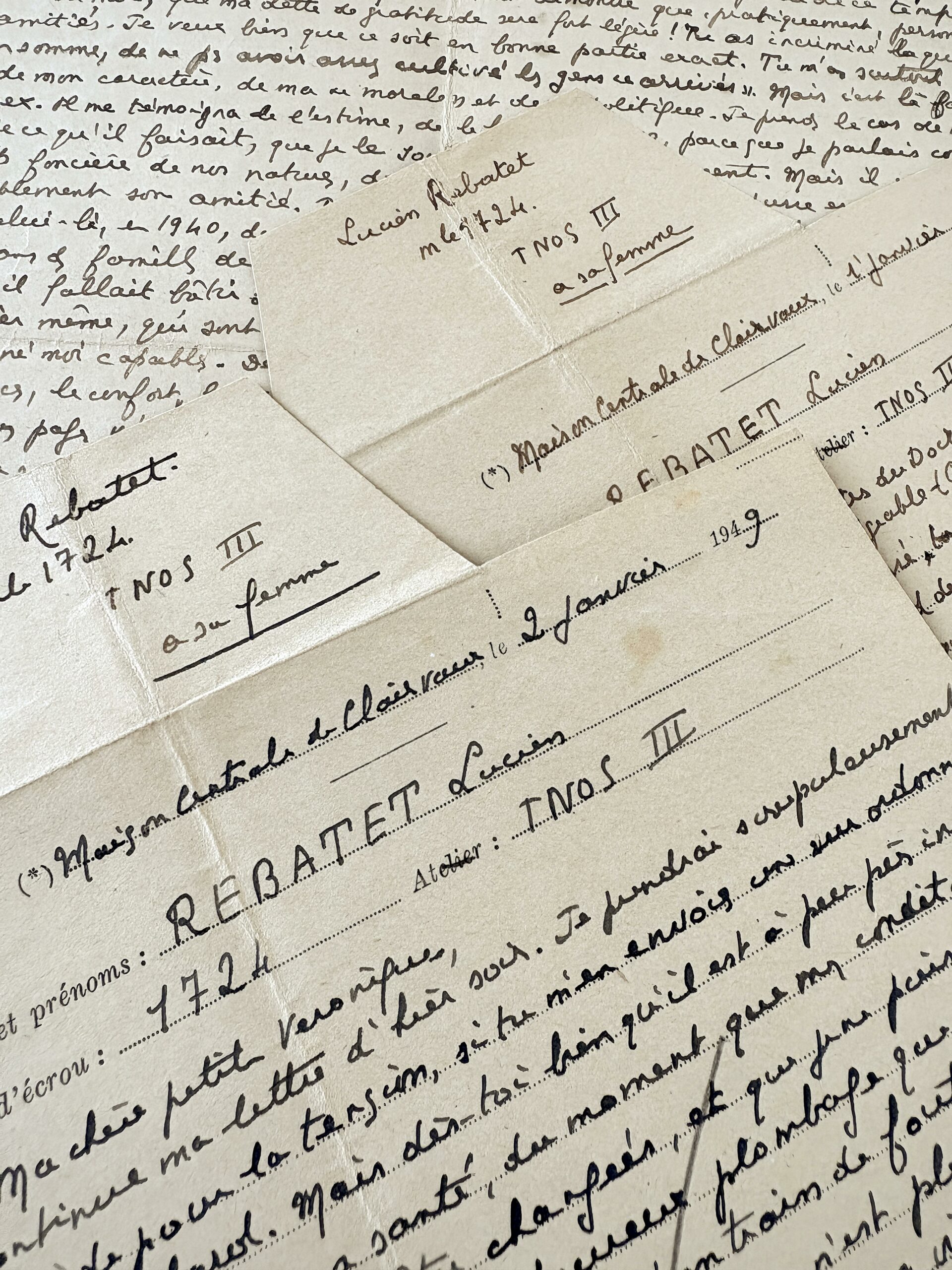

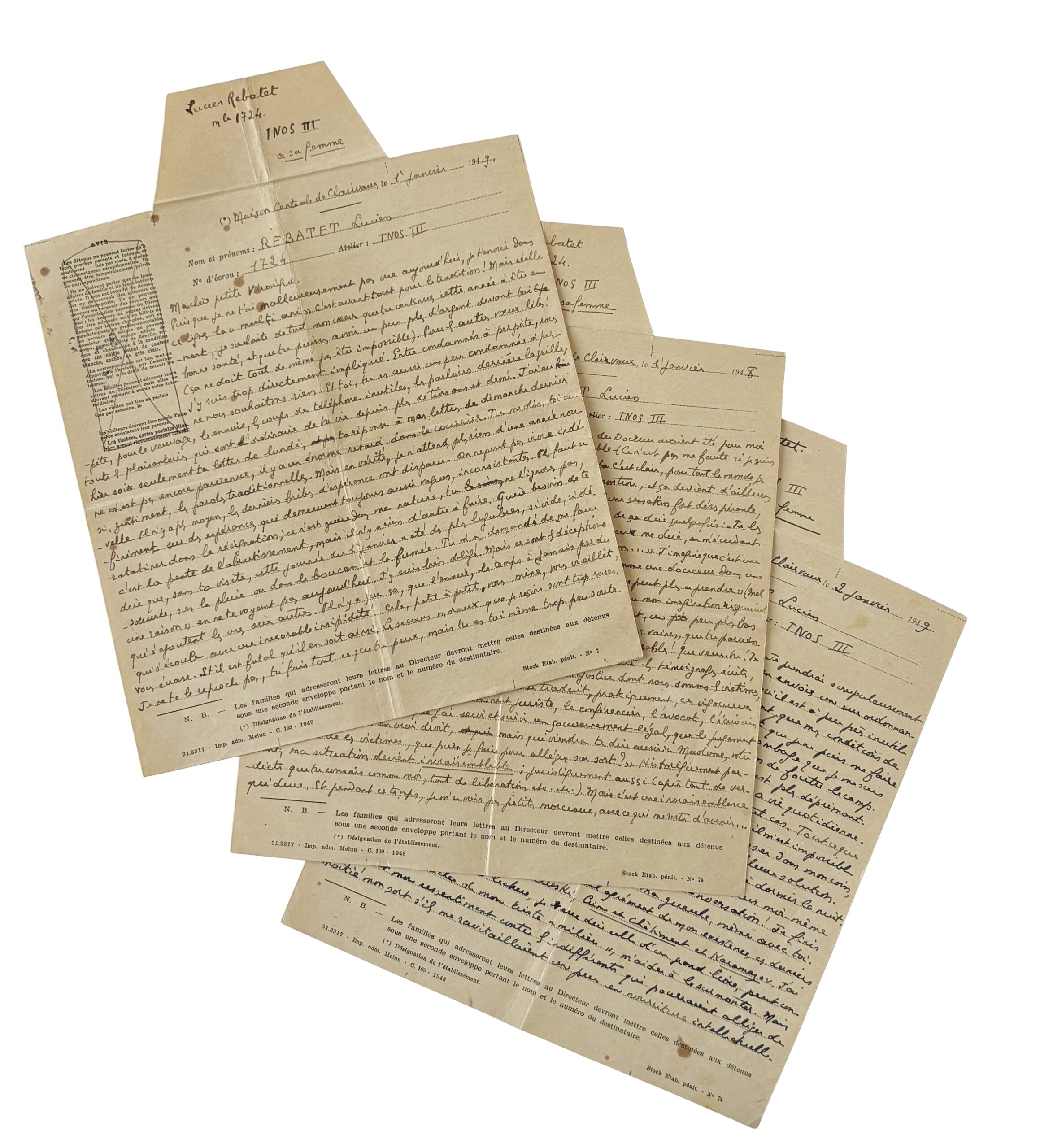

Autographed letter signed to his wife Véronique.

Six quarto pages on administrative paper from Clairvaux prison.

With nut numbers (1724) and workshop number (Tnos III).

Clairvaux Central Prison. January 1st and 2nd, 1949 .

"I also have the right to believe that I am paying for my love of the truth."

Overwhelmed by the despair of imprisonment and wasted hours, the author of The Ruins writes a long and dense letter, with pathetic overtones, to his wife.

Regretting Louis-Ferdinand Céline's "abandonment" of him, Rebatet stubbornly defends his past anti-Semitic actions in the name of what he considers honor and truth. Without hope or future, dead to society and literature, the imprisoned author sinks inexorably into the depths of a meaningless life, his days only occasionally redeemed by reading Dostoevsky's masterpieces.

Initially sentenced to death then pardoned in 1947 by Vincent Auriol and sentenced to forced labor for life, Rebatet was imprisoned in Clairvaux prison until July 1952.

________________________________________________________

"My dear little Véronique, Since I unfortunately didn't see you today, I'm sending you these lines on the 'multi-anni'. It's primarily for tradition! But truly, I sincerely wish you continued good health this year, and that you might have a little more money (it can't be impossible, surely).".

As for the other wishes, alas! I'm too directly involved. Between those condemned to life imprisonment, we wish each other nothing. And you, you too are somewhat condemned to life imprisonment, for widowhood, the troubles, the useless phone calls, the visits behind bars, all the jokes that have been the norm of your life for over three and a half years.

I only received your letter from Monday last night; your reply to my letters from last Sunday hasn't arrived yet—there's a huge delay with the mail. You so kindly say the usual things. But in truth, I no longer expect anything from a new year. There's no way; the last vestiges of hope have vanished. One cannot live indefinitely on hopes that remain so vague and inconsistent. One must shrink into resignation ; it's hardly in my nature, as you know, it's the slippery slope to despair , but there's nothing else to be done.

It hardly needs to be said that, without your visit, this January 1st was one of the most dismal days , so empty, so idle, in the rain or amidst the noise and smoke. You asked me to accept it, not seeing you today. I have no choice but to. But it's just one disappointment after another. There's nothing but boredom, time forever lost, slipping away with inexorable blandness . Little by little, it wears you down, ages you, crushes you. And it's inevitable that it should be so. The moral support I receive is far too infrequent. I don't blame you; you do everything you can, but you yourself receive far too little support.

Without anything being changed administratively, my situation, even in Clairvaux, could be less desolate, if I had a family and friends who took charge of part of the parcels, which would allow you to come and see me for example twice a month, if from time to time magazines and books were sent to me that would connect me a little to what was my life, to devote some studies at least part of this terribly wasted time.

You have remarkably demonstrated to me that, practically speaking, no one cares about me, that my debt of gratitude will be very small indeed! You have criticized the quality of my friendships. I grant that this is largely true. You have mainly reproached me, in short, for not having cultivated the "successful" people enough. But that is putting my character, my "morals," and my politics on trial. I take the case of René Clair, for example. He showed me esteem and goodwill because I spoke appropriately of what he did and supported him quite effectively. But there was too fundamental a contradiction between our natures and our beliefs for me to truly hope for his friendship. Quite frankly, what would you have thought of me if I had been like him, in 1940, part of the small group fleeing their unfortunate country, with women born into families of rabbis or diamond merchants?

To truly be with certain people, one had to build one's life on a cynicism, a greed that we can envy, even admire, that may be the only recipe for happiness, but which neither you nor I are capable of. Since reaching adulthood, I have always sacrificed money, positions, comfort, and flattering relationships to the ambition of leaving behind a few truthful , pages that can therefore be reread in sixty years. It seems to me, moreover, that this is why you became attached to me (for it is neither my charms nor my good looks that I could invoke, is it?).

I readily admit that I was more naive than I should have been; I'll explain myself publicly one day, if I don't die here. But I also have the right to believe that I'm paying a truly exorbitant price for my love of truth , since it's not even about my freedom or my pleasures, but about my health and my talent, which are becoming more and more cruelly compromised every day. That's what everyone has forgotten. I had foreseen it, I wrote to you about it, so I'm not surprised. But I can't hide from you that this indifference is doing much to darken my life and break what little strength I had left .

You probably feel some satisfaction seeing that you were right about the doctor [Louis-Ferdinand Céline], since he finally abandoned me. I'm certainly not making a big deal out of this abandonment; I'm taking it in stride, quite philosophically (I have such a heavy burden, and I'm so used to it!). You must understand, however, that it's still a little sad for me, that if the doctor had remained faithful, he would have been a small bright spot in my otherwise bleak and dreary life.

For over two years, the Doctor's letters had been a significant intellectual stimulus for me (it's not my fault I'm an intellectual). The Doctor has grown tired of them. Clearly, as far as everyone is concerned, I'm finished, done for, at rock bottom, and that's becoming increasingly true.

You'll agree that it's a very disheartening feeling, and one that doesn't compensate for the small satisfaction of sometimes saying to myself, "I don't give a damn about them." I don't understand what you meant when you wrote to me last Monday, "in six months maximum." I imagine it was a little word of comfort you wanted to slip me for New Year's, like a treat in a package. But in all honesty, my dear, it's pointless. Because it can't "work" anymore (Put yourself in my shoes!). If it did, it would be a great shame because my imagination might start running wild, ultimately leading me to another leap, a little deeper into the abyss.

I sincerely hope that your current efforts will not be in vain, that you will achieve some small result. But so small, even in the most optimistic predictions! What can you expect! I observe that written testimonies, judicial, diplomatic, financial, and other evidence of the injustice of which we are victims—myself and a number of others—are accumulating in an increasingly impressive manner .

But what does this vigorous concert translate into, practically speaking? Zero. I'm still waiting for the eminent jurist, the lecturer, the lawyer who can so eloquently demonstrate that I served and followed a lawful government, that the judgment against me is null and void in true legal terms, but who will also come and tell you: "Madam, your husband is one of these victims. What can I do to alleviate his suffering?" Historically speaking, my situation is becoming implausible ; legally as well (after so many verdicts that you know as well as I do, so many acquittals, etc., etc.). But it's an implausibility that persists. And all the while, I'm slipping away in small pieces, with what little future I have left …

My darling Minette, what you wrote to me on Monday about your situation breaks my heart. That you can no longer even afford the bare necessities, that you are increasingly reduced to this life of poverty. And to think that if I were outside, in 15 days, I could change everything! I am very worried about you. Where will this lead you? Seriously, what do you hope for? I fear you are living in a fantasy world … You can't go on like this much longer. There must be some way out. How I wish that, after you have achieved a positive or negative result in your current efforts, you could finally, for a few months, take care of yourself, and only .

I'm dedicating a few lines to a less somber subject. I saw in a magazine that there's currently an exhibition at the Petit Palais, I believe, of the finest paintings from the Munich Pinakothek, as well as those from Vienna last year. I urge you to find out immediately how long this exhibition will run, as it must have been open for some time already, and to spend two or three hours there as soon as possible. The Pinakothek was one of the most beautiful museums in the world. I spent a long time there in the winter of 1937, while you were staying at the Hôtel du Mont-Blanc. You may never have the chance to see those paintings again. I want you to have the same memory of them as I do, so that we can talk about them together someday. I especially recommend the Rubens, the finest collection in existence: The Battle of the Amazons, The Rape of the Sons of Leucippus , The Judgment of the Innocents. […]

After detailing the treasures of the Pinacothèque exhibited in Paris, the Rembrandts, Dürers and Cranachs " of a very German taste, but so full of fantasy ", but also canvases by Tintoretto, Tiepolo, Goya, Greco, Botticelli, the Flemish primitives, etc. " My pictorial memory is still quite good ", Rebatet concludes the first part of this letter begun on 1st :

" I'll write to you tomorrow morning […] Good evening, my dear Minette, I kiss you. See you tomorrow. Lucien."

My dearest little Véronique, I'm continuing my letter from last night. I will scrupulously take the blood pressure medication if you send me a prescription from Chaucharol. But keep in mind that it's practically pointless to worry about my health as long as my living conditions can't be changed, and I can't get my teeth fixed. The wretched filling I had put in last year is falling out. I have a dull toothache two days out of three. Nothing is more depressing. You're sometimes surprised that I never tell you anything about my daily life. It's because it's unspeakable in the current circumstances, at least. All I can tell you is that, basically, from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., it's impossible for me to do anything. Often, I end up curling up in my corner , dozing off as best I can, because it's still the best solution. The annoying thing is that in those situations, I can't sleep at night anymore.

You must be tired of hearing my whining, and I'm tired of it myself. But I have so little to talk about! I'm beginning to think it would be more dignified to keep my mouth shut , even with you. As I've already said, the only enjoyment in my existence lately has been reading Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment and Karamazov . I've found how much a great book—I mean a great one—can help me detach myself from my dreary "environment," help me overcome it. But it also increases my resentment toward the indifferent people who could halve my lot if they would only provide me with a little intellectual nourishment.

This winter, I would have loved to delve deeper into Dostoevsky's work, something I haven't done in over twenty years, and for which I am remarkably receptive. Wouldn't it be possible to obtain from a generous donor a copy of *The Idiot* and *The Possessed* , in the NRF edition , the only complete and reliable one, as well as the best French biography of Dostoevsky ?

I left a few lines on this page, hoping for your reply to my letters from Sunday, but the mail has just been delivered and there's nothing for me . I would have been truly spoiled for the holidays. I know it's not your fault; there's a real mail jam. I'm so glad you wrote me a little note on Monday, without waiting for my letters, otherwise I would have gone the whole week without any news at all. I'm certainly one of those who receives the least mail. Please, don't forget to send me two little notes a week.[…]

Try to come see me one of these Sundays. It's not so much that I'm eager for details about your plans, but I'd like to see you. Try to keep warm, take care of yourself, don't do anything reckless. We're both becoming increasingly unhappy. How far will this go?[…]

Answer these letters quickly so we can resume normal correspondence. Don't miss the exhibition at the Pinacothèque. I love you with all my heart, my dear Minette, but our shoulders are both truly too heavy. I'm not living anymore, I'm just dragging myself along. I kiss you long, but sadly. Lucien .

________________________________________________________

In 1942, Lucien Rebatet published Les Décombres, a pamphleteering pinnacle of anti-Semitic abjection. A critic, writer, and journalist, his writing, written during the Vichy regime, reeked of a furious hatred of Jews, whom he blamed for the national defeat of 1940.

As Nazi Germany collapsed, Rebatet fled to Germany and reached Sigmaringen with other collaborators and exiles, including Louis-Ferdinand Céline. He was arrested in Austria on May 8, 1945, the very day of the armistice, and tried on November 18, 1946. Rebatet was sentenced to death.

Thanks to a petition signed by writers including Camus, Mauriac, Paulhan, Bernanos, Aymé, and Anouilh, Rebatet was pardoned on April 12, 1947, by President Vincent Auriol. His death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment with hard labor.

He finished in prison a novel begun in Sigmaringen, *The Two Standards *, published by Gallimard in 1952 thanks to the support of Jean Paulhan. This work remains considered a masterpiece by many readers and critics. François Mitterrand is said to have remarked about it: "There are two kinds of men: those who have read *The Two Standards* , and the others."