Marcel Proust (1871.1922)

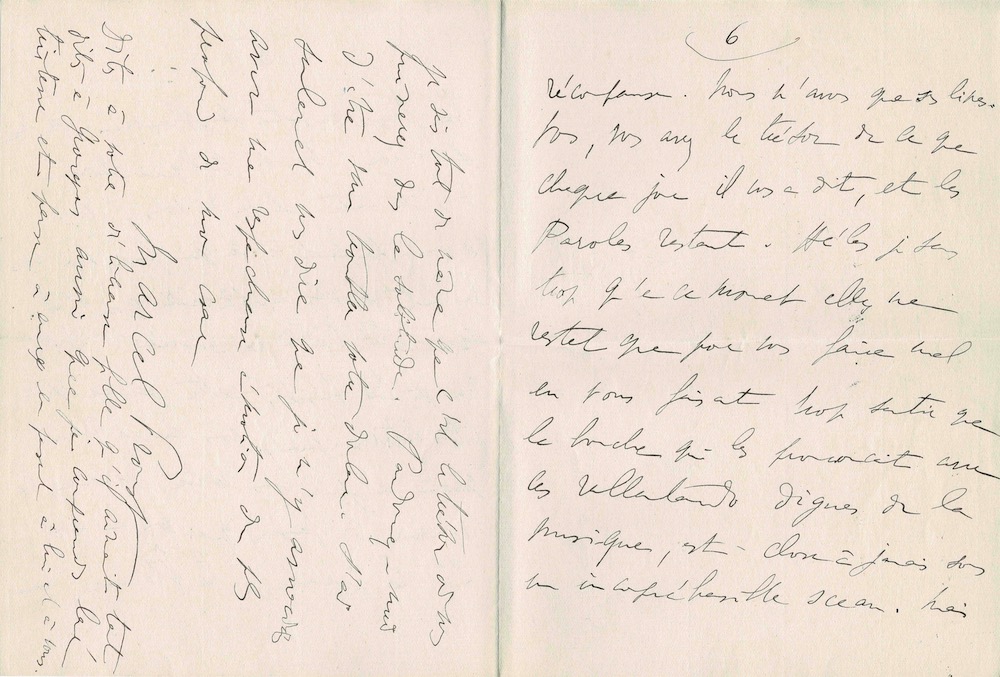

Autographed letter signed to Baroness Aimery Harty de Pierrebourg.

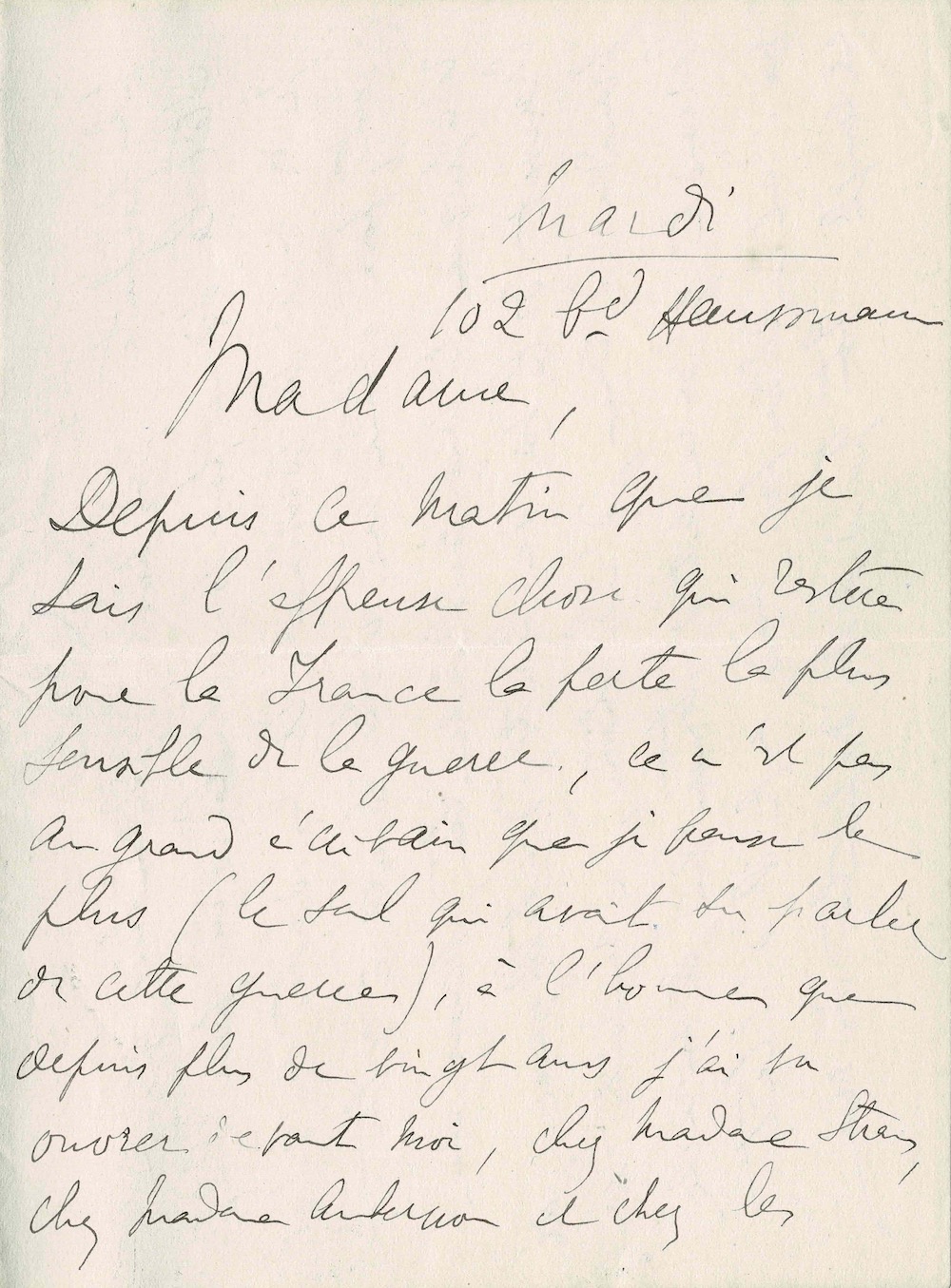

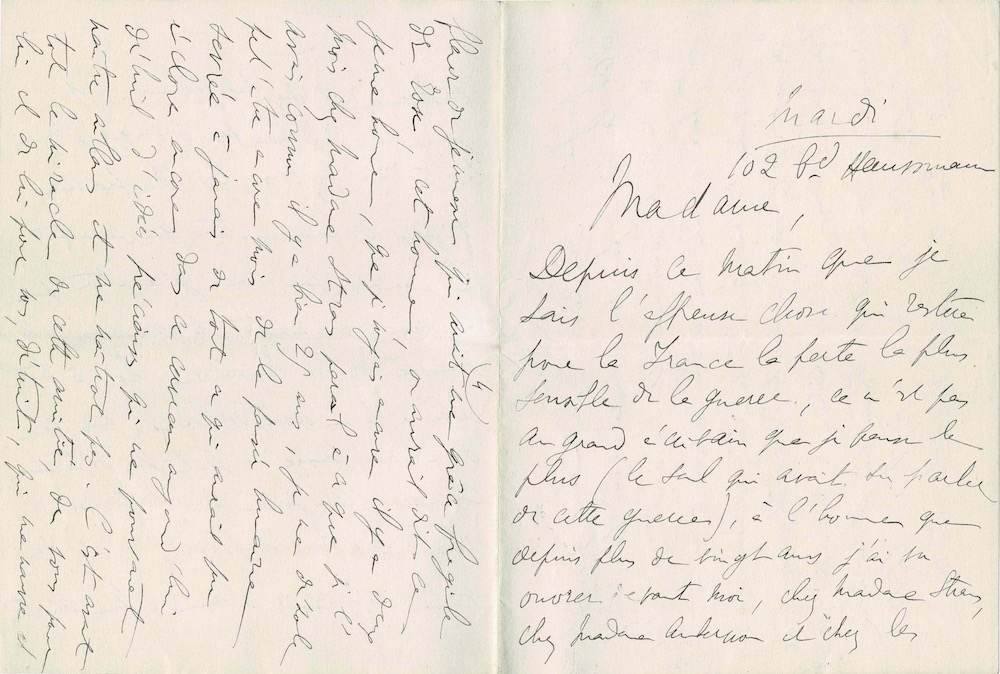

Seven pages in-8°. 102 bd Haussmann. Tuesday [October 26, 1915]

Kolb, Volume XIV, pages 252 to 254.

Paul Hervieu, the illustrious lover of Madame de Pierrebourg, has just died. Marcel Proust expresses to her, with sublime prose, the extent of his friendship in these circumstances of mourning.

"And when I see this man disappear in a flower of youth, a man with the fragile grace of a rose—this man, who looked like the young man I saw just two months ago at Mrs. Straus's house, just as I had known him some twenty-five years ago—I am perhaps even less saddened by the human thought, forever deprived of all that could still have blossomed in this brain, now destroyed, with precious ideas that could not be born elsewhere and will not be born."

____________________________________________________________

"Madam, Since this morning I learned of the dreadful thing which will remain for France the most sensitive loss of the war [the death of Paul Hervieu had just been announced by Le Figaro] , it is not the great writer I think of most (the only one who knew how to speak of this war), the man whom for more than twenty years I have seen working before me, at Mme Straus's, at Mme Aubernon's and at the Baignères' and at M e Arman's, and I do not even mention because I would have too much to say, at your place, the most precious jewels of conversation which forever adorn for our generation, for its teaching and its joys, the Museum of his Memory.

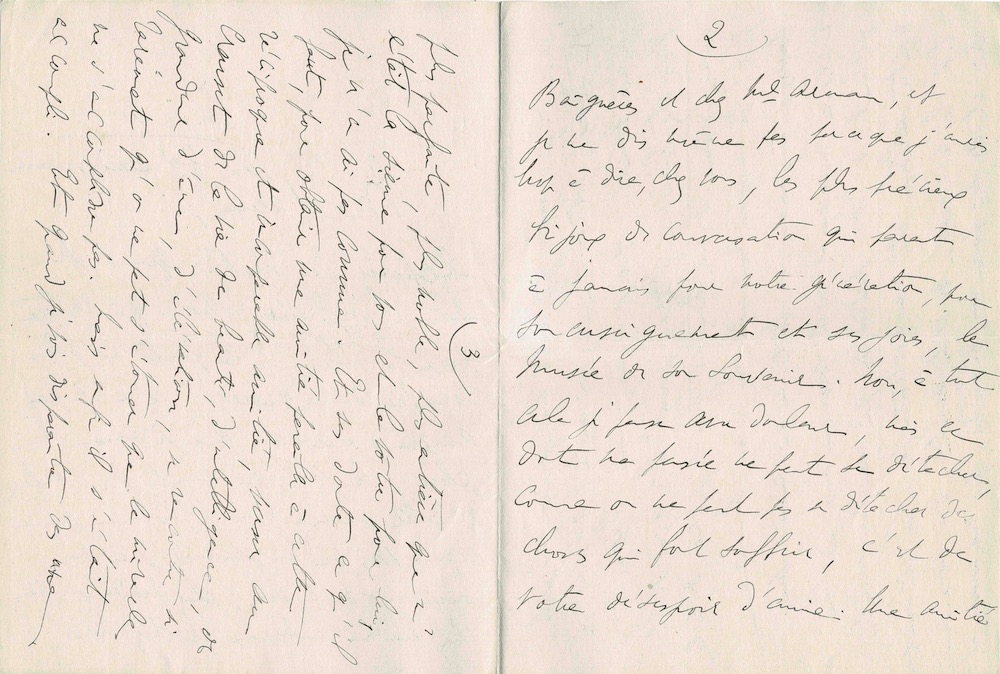

No, I think of all this with sorrow, but what my thoughts cannot detach themselves from, as one cannot detach oneself from things that cause suffering, is your despair as a friend. I have never known a friendship more perfect, more noble, more complete than his was for you and yours for him. And doubtless what is needed to obtain a friendship like this reciprocal and incomparable one—to pour into the crucible of life beauty, intelligence, magnanimity, and elevation—is so rarely encountered that one cannot be surprised that the miracle does not occur. But in the end, it did occur. And when I see this man, who had the fragile grace of a rose, disappear in a flower of youth—this man who seemed like the young man I saw just two months ago at Mrs. Straus's, exactly as I had known him some twenty-five years ago—perishing in a state of profound grief, I am perhaps even less saddened by the human spirit, forever deprived of all that might still have blossomed in this brain, now destroyed, with precious ideas that could not be born elsewhere and never will be. It is above all the miracle of this friendship, yours for him and his for you, now shattered, that grieves me, and the thought of your suffering.

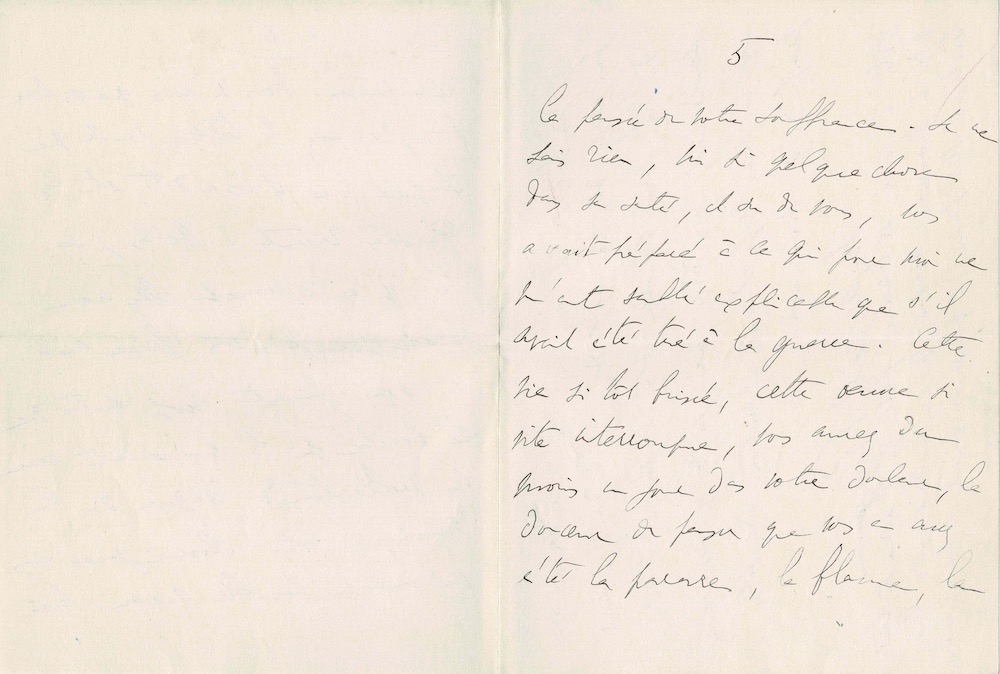

I know nothing, not even if something about his health, known to you, had prepared you for what, to me, would only have seemed explicable if he had been killed in the war. This life so soon cut short, this work so quickly interrupted—you will at least one day have, in your grief, the solace of thinking that you were its adornment, its flame, its reward. We have only his books. You have the treasure of what he told you each day, and the Words remain [allusion to a title by Hervieu].

Alas, I feel all too keenly that at this moment they remain only to cause you pain, making you acutely aware that the mouth which uttered them, with those rallentandos worthy of music, is forever sealed under an incomprehensible seal. But I know nonetheless that it is a treasure from which you will draw in solitude. Forgive me for having come to disturb your grief. I only wanted to tell you that I share in it with a respectful emotion from the depths of my heart. Marcel Proust.

Tell your lovely daughter whom he loved so much, and tell Georges too that I understand their sadness and am thinking of them as I think of him and you

________________________________________________

The stepmother of Georges de Lauris, one of Marcel Proust's friends whom he met in 1903 and who served as a trusted advisor for the writing of what would become * Contre Sainte-Beuve*, Marguerite de Pierrebourg (1856-1943) was initially a painter before turning to writing. Her first novel was recognized by the French Academy, and from 1912 she became president of the Prix de la Vie Heureuse (later the Prix Fémina), thus occupying an important place in Parisian literary life. Marcel Proust frequented her salon and consulted her on literary matters. She was notably one of the witnesses to the difficult gestation of the first volume of * In Search of Lost Time*.