André Breton (1896.1966)

Autograph manuscript signed – PHÉNIX DU MASQUE.

Four quarto pages on blue paper. No place of publication [December 1960]

Ensign signed by Breton at the head of the manuscript [probably to Gualtieri di San Lazzaro]

"He firmly embraces the surrealist aim of shielding the mask from the winds of derision and the defilements of carnival."

As a knowledgeable connoisseur, André Breton analyzes in retrospect the success of the exhibition "The Mask" which was held at the Guimet Museum during the first half of 1960. The surrealist herald, an inveterate collector of primitive art, extols, in this text intended for the 20th Century (founded by Gualtieri di San Lazzaro), the hypnotic virtues of adornment and the mask, open doors to the lands of the unconscious, constituting a form of surrealist ideal.

_________________________________________

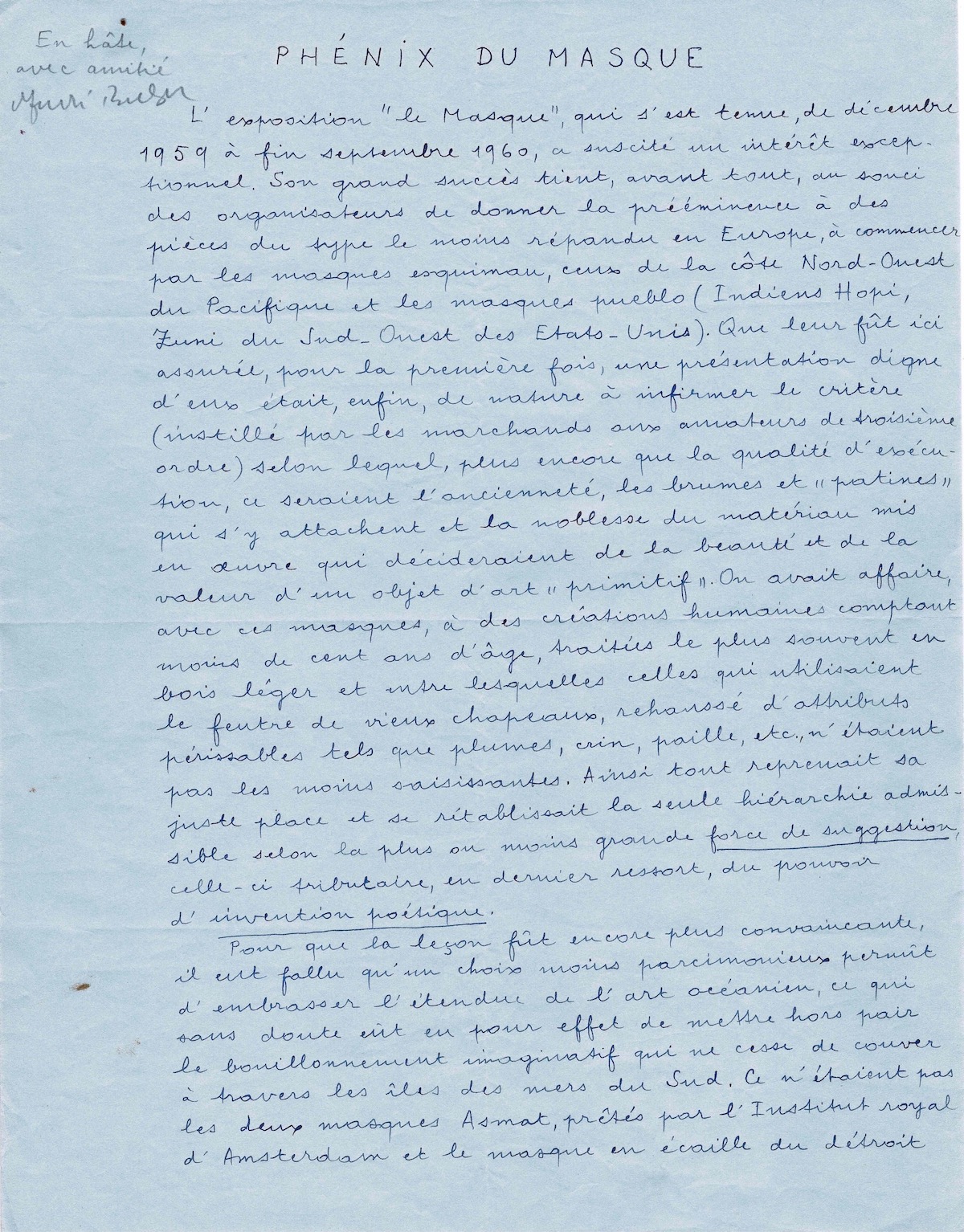

"In haste, with friendship, André Breton."

PHOENIX OF THE MASK

The exhibition "The Mask," held from December 1959 to the end of September 1960, aroused exceptional interest. Its great success stemmed, above all, from the organizers' concern to give prominence to pieces of the least common type in Europe, beginning with Inuit masks, those from the Pacific Northwest coast, and Pueblo masks (Hopi Indians, Zuni of the Southwestern United States). The fact that they were presented here, for the first time, in a manner worthy of them was, finally, likely to refute the criterion (instilled by dealers in third-rate collectors) according to which, even more than the quality of execution, it was the age, the mists and "patinas" that cling to them, and the nobility of the material used that determined the beauty and value of a "primitive" work of art. These masks were human creations less than a hundred years old, most often made of lightweight wood, and among them, those made from the felt of old hats, enhanced with perishable materials such as feathers, horsehair, straw, etc., were among the most striking. Thus, everything fell into place, and the only admissible hierarchy was re-established, based on the greater or lesser power of suggestion , which ultimately depended on the power of poetic invention .

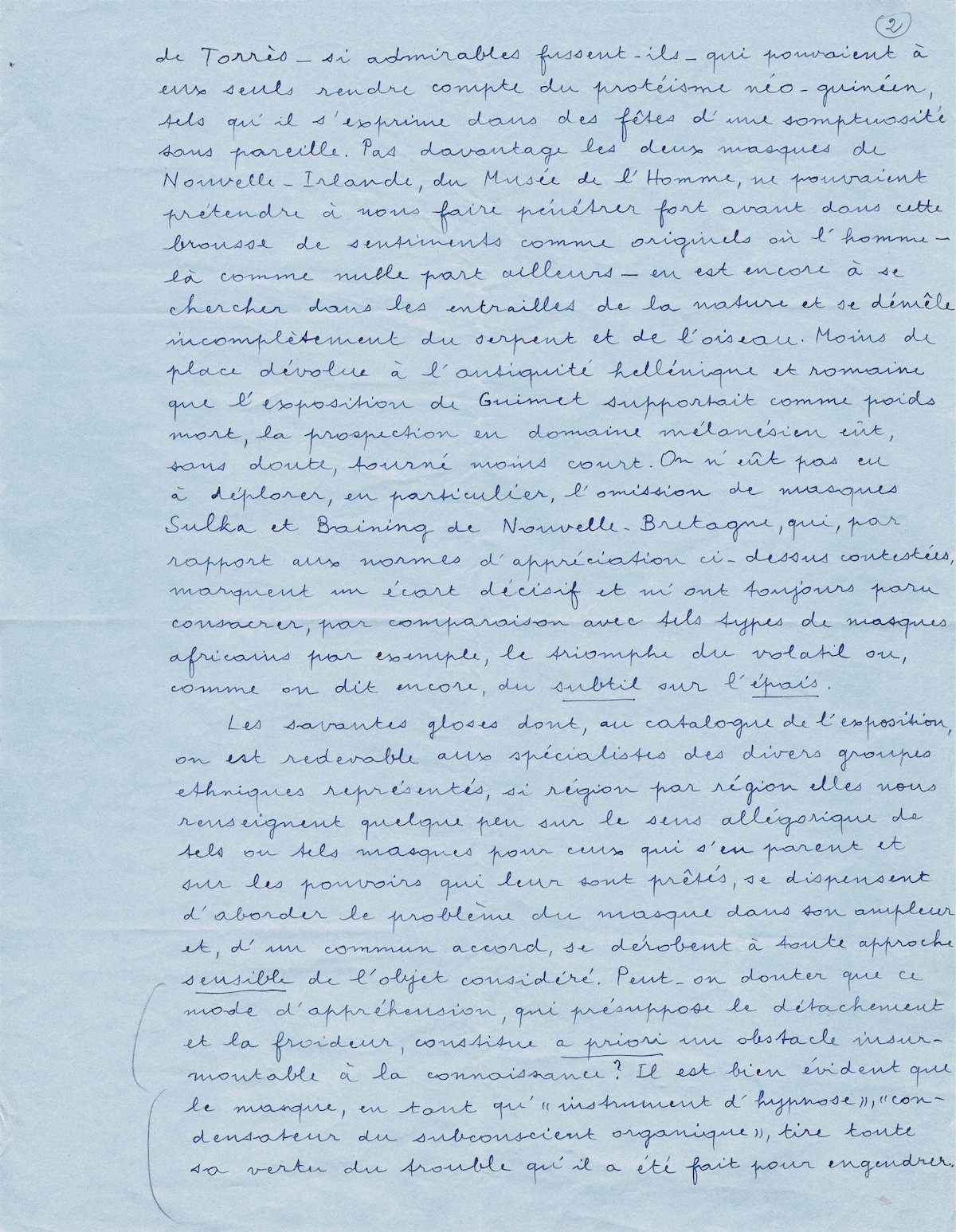

For the lesson to be even more convincing, a less parsimonious selection would have been necessary to encompass the breadth of Oceanic art , which would undoubtedly have highlighted the vibrant imaginative energy that constantly simmers throughout the islands of the South Seas. The two Asmat masks, on loan from the Royal Institute of Amsterdam, and the tortoiseshell mask from the Torres Strait—admirable as they were—could not alone account for the protean nature of New Guinea, as expressed in festivals of unparalleled splendor. Nor could the two masks from New Ireland, in the Musée de l'Homme, presume to lead us far into this thicket of primal feelings where humankind—there as nowhere else—is still searching for itself in the bowels of nature and incompletely disentangling itself from the serpent and the bird. With less space devoted to Hellenic and Roman antiquity, which the Guimet exhibition carried as dead weight, the exploration of the Melanesian realm would undoubtedly have been less incomplete. In particular, one would not have had to lament the omission of Sulka and Braining masks from New Britain, which, in relation to the aforementioned contested standards of appreciation, mark a decisive departure and have always seemed to me to consecrate, by comparison with certain types of African masks for example, the triumph of the ephemeral or, as it is still said, the subtle over the crude .

The scholarly commentaries in the exhibition catalog, provided by specialists of the various represented ethnic groups, while offering some insight into the allegorical meaning of certain masks for those who wear them and the powers attributed to them, avoid addressing the broader issue of the mask and, by common agreement, steer clear of any sensitive to the object in question. Can we doubt that this mode of understanding, which presupposes detachment and coldness, constitutes insurmountable obstacle to knowledge? It is quite clear that the mask, as an "instrument of hypnosis," a "condenser of the organic subconscious," derives all its power from the disturbance it was designed to generate.

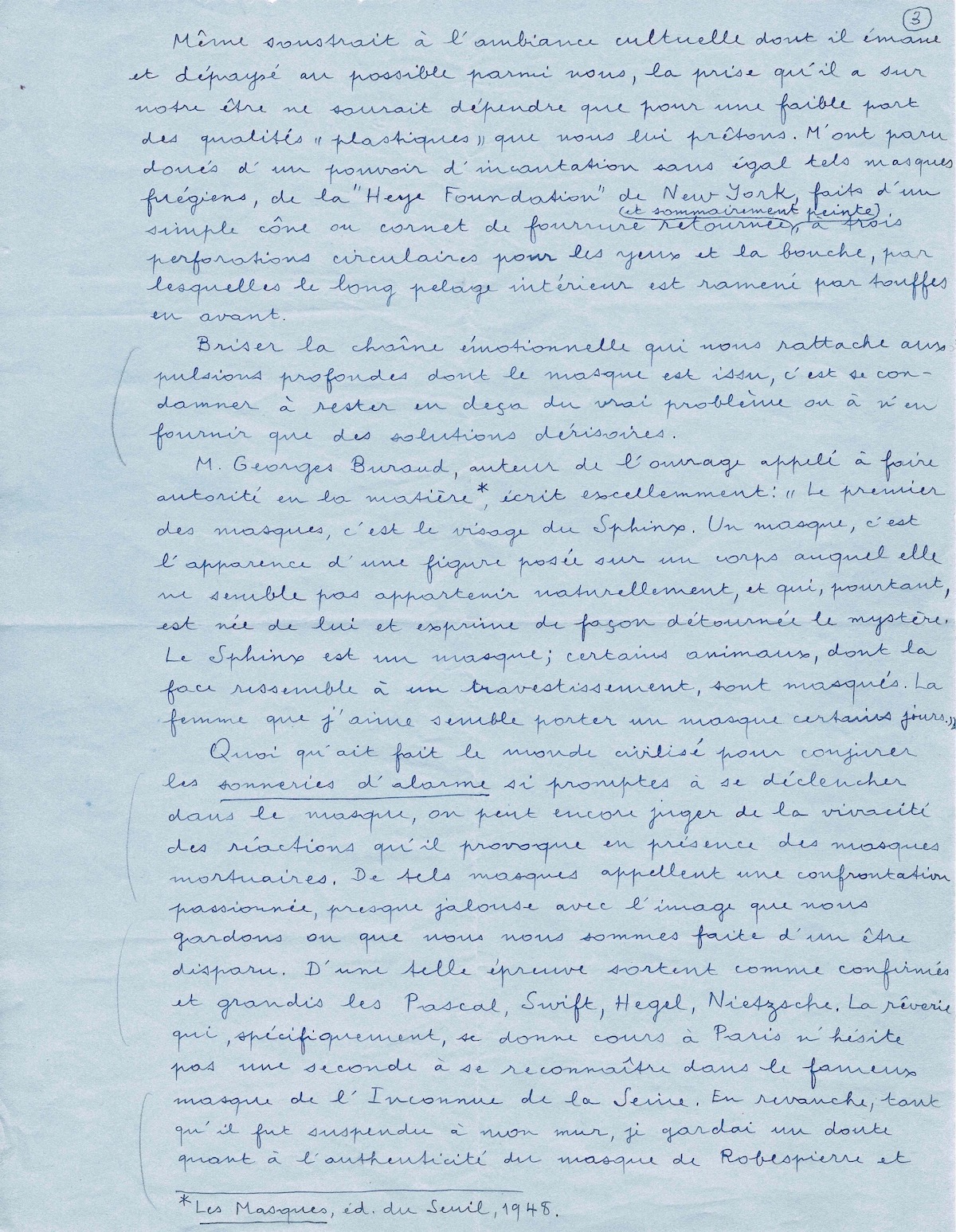

Even when removed from the cultural context from which it originates and placed as out of place as possible among us, its hold on our being can only depend to a small extent on the "plastic" qualities we attribute to it. I was struck by the unparalleled power of incantation found in certain Fregean masks from the "Heye Foundation" in New York, made of a simple cone or horn of fur turned inside out and summarily painted, with three circular perforations for the eyes and mouth, through which the long inner fur is pulled forward in tufts.

Breaking the emotional chain that ties us to the deep impulses from which the mask originates is to condemn ourselves to remaining short of the real problem or to providing only derisory solutions.

Mr. Georges Buraud, author of the definitive work on the subject [Les Masques, published by Seuil, 1948], writes excellently: “ The first of the masks is the face of the Sphinx. A mask is the appearance of a figure placed on a body to which it does not seem to naturally belong, and which, nevertheless, is born from it and expresses the mystery in a striking way. The Sphinx is a mask; certain animals, whose strength resembles a disguise, are masked. The woman I love seems to wear a mask on certain days.”

Whatever the civilized world may have done to ward off the alarm bells so quick to ring in the face of the mask, one can still judge the intensity of the reactions it provokes in the presence of death masks. Such masks call for a passionate, almost jealous confrontation with the image we retain or have formed of a deceased person. From such an ordeal emerge, as if confirmed and magnified, figures like Pascal, Swift, Hegel, and Nietzsche. The reverie that specifically takes hold in Paris does not hesitate for a second to recognize itself in the famous mask of the Unknown Woman of the Seine. On the other hand, however much it hung on my wall, I will always harbor doubts about the authenticity of Robespierre's mask, and nothing drove Paul Éluard to distraction like hearing it claimed that the mask attributed to Baudelaire could truly be his.

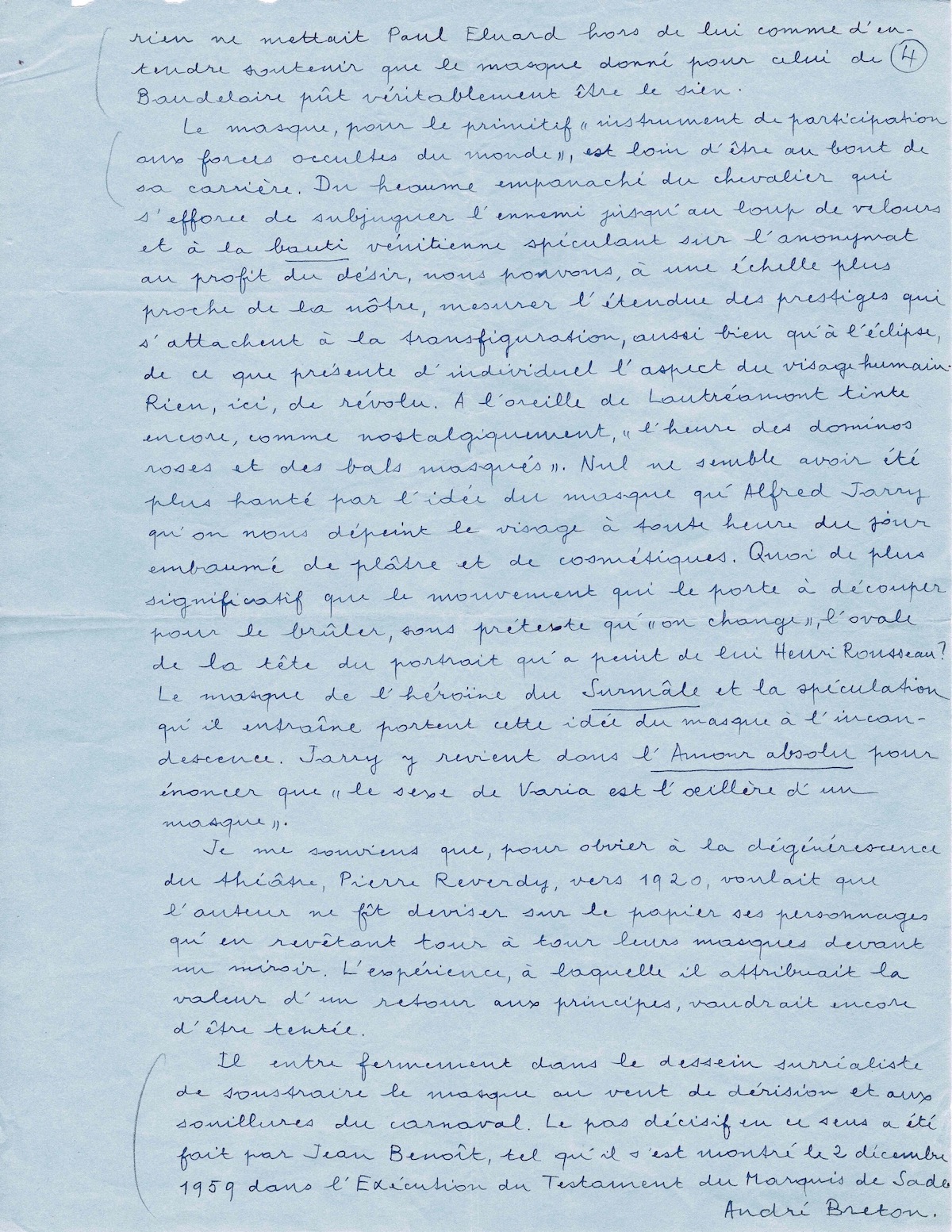

The mask, for primitive man, was an “instrument of participation in the occult forces of the world,” and its story is far from over. From the plumed helmet of the knight striving to subjugate the enemy to the velvet mask and the bauti , which exploit anonymity for the sake of desire, we can, on a scale closer to our own, measure the extent of the prestige attached to the transfiguration, as well as the eclipse, of the individual aspects of the human face. Nothing here is truly bygone. In Lautréamont’s ear, the “hour of pink dominoes and masked balls” still rings, as if nostalgically. No one seems to have been more haunted by the idea of the mask than Alfred Jarry, whose face is depicted at all hours of the day, embalmed with plaster and cosmetics. What could be more significant than the impulse that leads him to cut out and burn, under the pretext of "changing," the oval of the head in the portrait Henri Rousseau painted of him? The mask of the heroine of The Supermale and the speculation it engenders bring this idea of the mask to a fever pitch. Jarry returns to it in Absolute Love to state that "Varia's sex is the blinder of a mask."

I remember that, around 1920, to counteract the decline of theatre, Pierre Reverdy wanted playwrights to only write down their characters' dialogue by putting on their masks one after the other in front of a mirror. He considered this experiment a return to basic principles, and it would still be worth trying.

He firmly embraces the surrealist aim of freeing the mask from the winds of derision and the defilements of carnival. The decisive step in this direction was taken by Jean Benoît, as he demonstrated on December 2, 1959, in *The Execution of the Marquis de Sade's Testament*. André Breton.

_________________________________________

Bibliography:

Phoenix of the Mask, André Breton, Cavalier Perspective, Complete Works.

Writings on art and other texts , Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, pp. 990-996.

20th Century , New Series, No. 15, Christmas 1960.