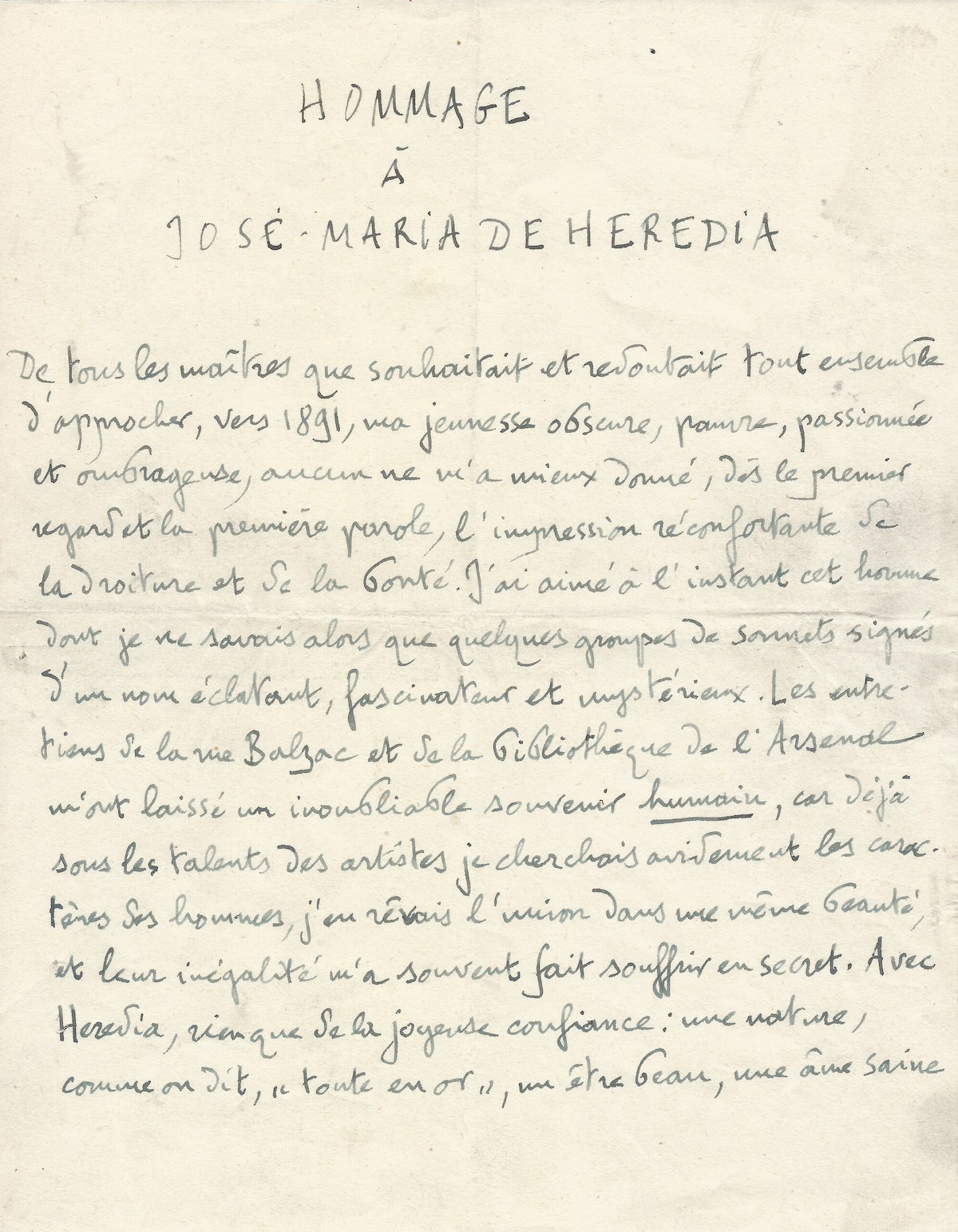

Camille MAUCLAIR (1872.1945)

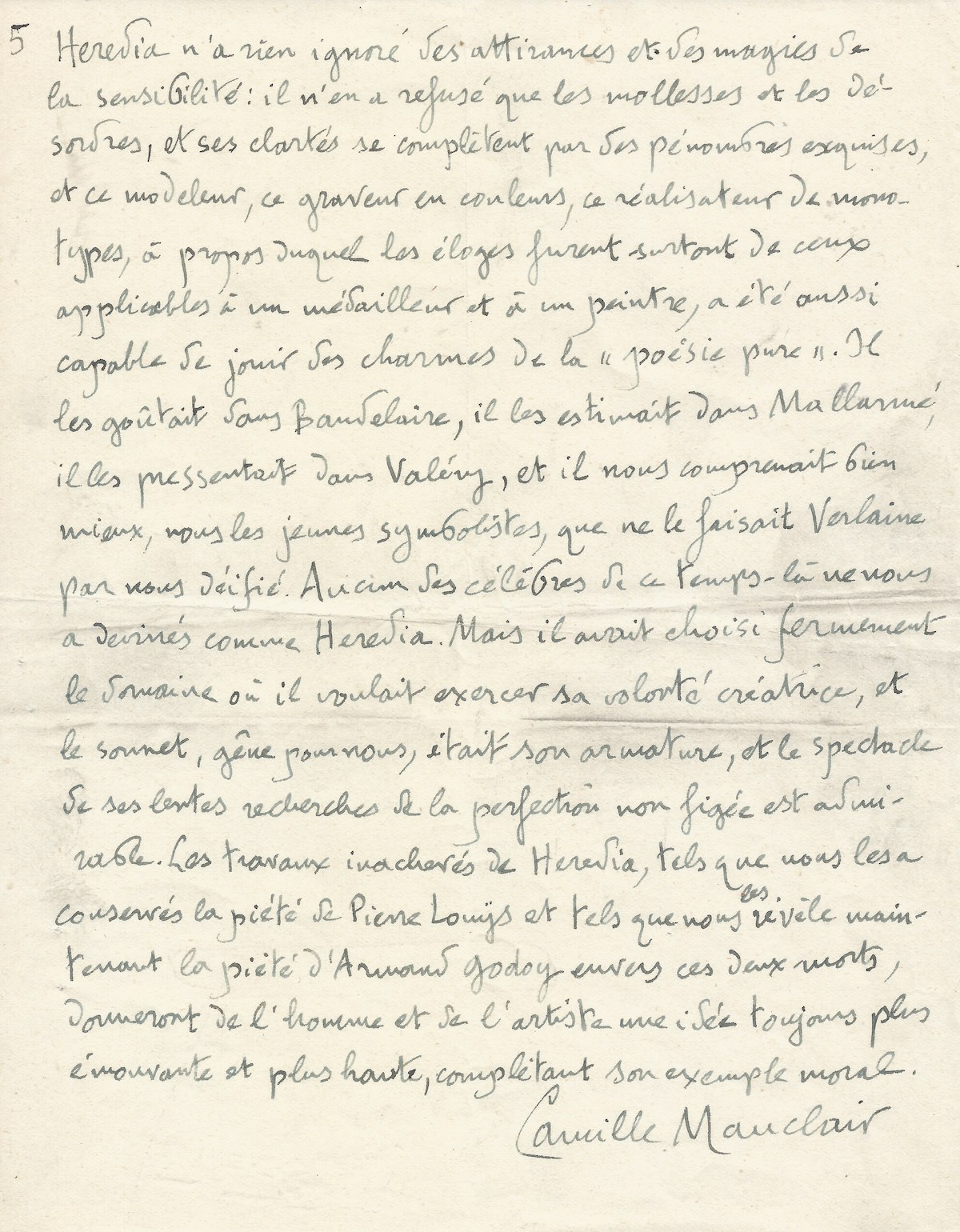

Signed autograph manuscript – Heredia.

Five pages in-4° numbered in the corner.

Slnd. [1925 or 1926]

“I instantly loved this man of whom I only knew a few groups of sonnets signed with a dazzling, fascinating and mysterious name.”

Following the publication of Armand Godoy's tribute book on Heredia, in 1925 by Alphonse Lemerre, Camille Mauclair praises the art of the sonnet and the greatness of soul of the Franco-Cuban poet.

_______________________________________________________

TRIBUTE TO JOSÉ MARIA DE HEREDIA.

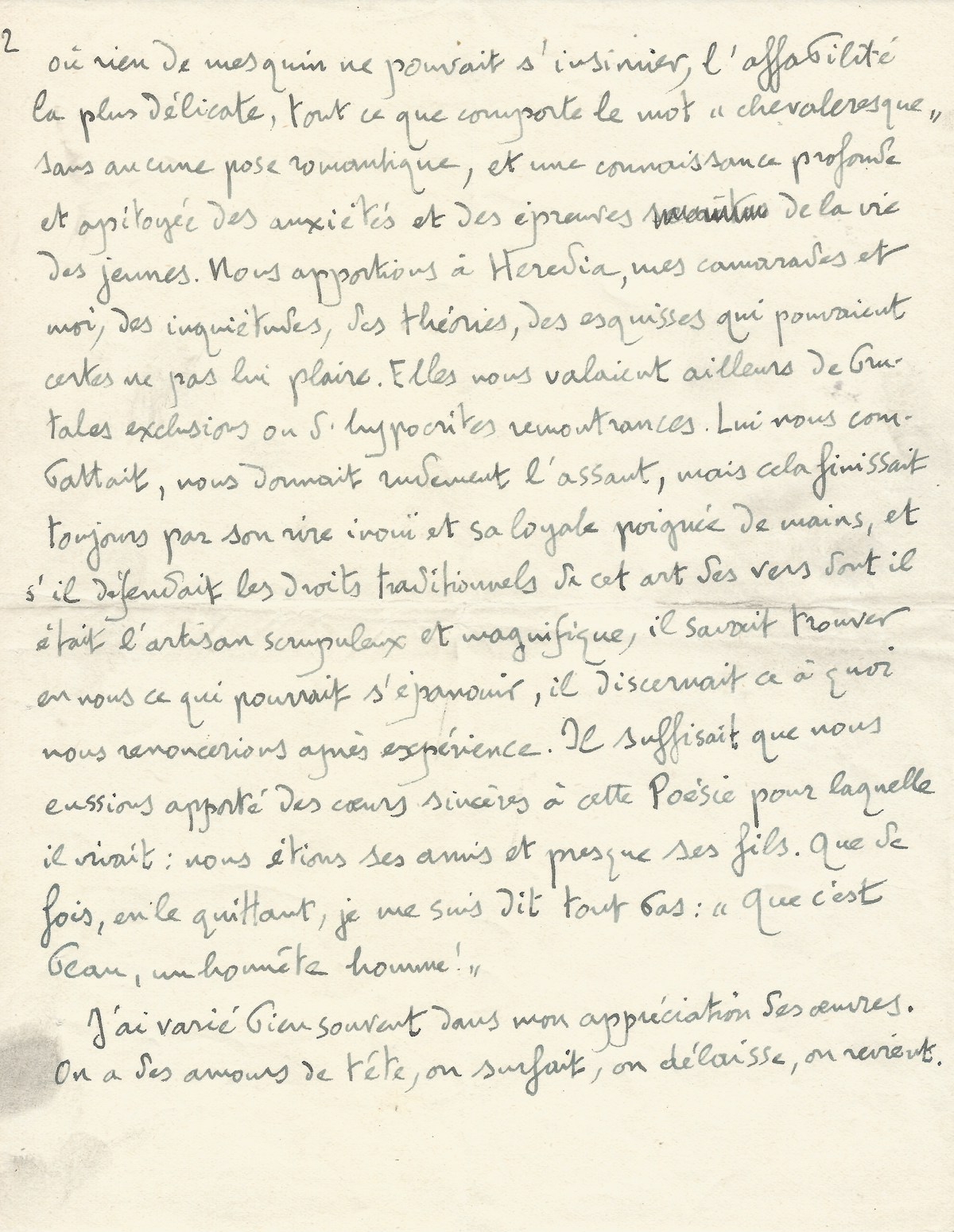

“Of all the masters that my obscure, poor, passionate and shady youth wanted and feared to approach, around 1891, none gave me better, from the first look and the first word, the comforting impression of righteousness and kindness. I instantly loved this man of whom I only knew a few groups of sonnets signed with a dazzling, fascinating and mysterious name.

The conversations in rue Balzac and at the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal left me with an unforgettable human , because already under the talents of the artists I was eagerly seeking the characters of men, I dreamed of their union in the same beauty, and their inequality has often made me suffer in secret. With Heredia, nothing but joyful confidence: a nature, as they say, "all in gold", a beautiful being, a healthy soul where nothing petty could creep in, the most delicate affability, everything that features the word “chivalrous” without any romantic posturing, and a deep, pitying knowledge of the anxieties and trials of young life.

We brought Heredia, my comrades and I, concerns, theories, sketches which might, of course, not please him. Elsewhere, they earned us brutal exclusions or hypocritical reprimands. He fought us, violently attacked us, but it always ended with his incredible laughter and his loyal handshake, and if he defended the traditional rights of this art, his verses of which he was the scrupulous and magnificent craftsman, he knew how to find in us what could flourish, he discerned what we would give up after experience. It was enough that we had brought sincere hearts to this poetry for which he lived: we were his friends and almost his sons. How many times, when leaving him, I said to myself quietly: “How beautiful an honest man is! »

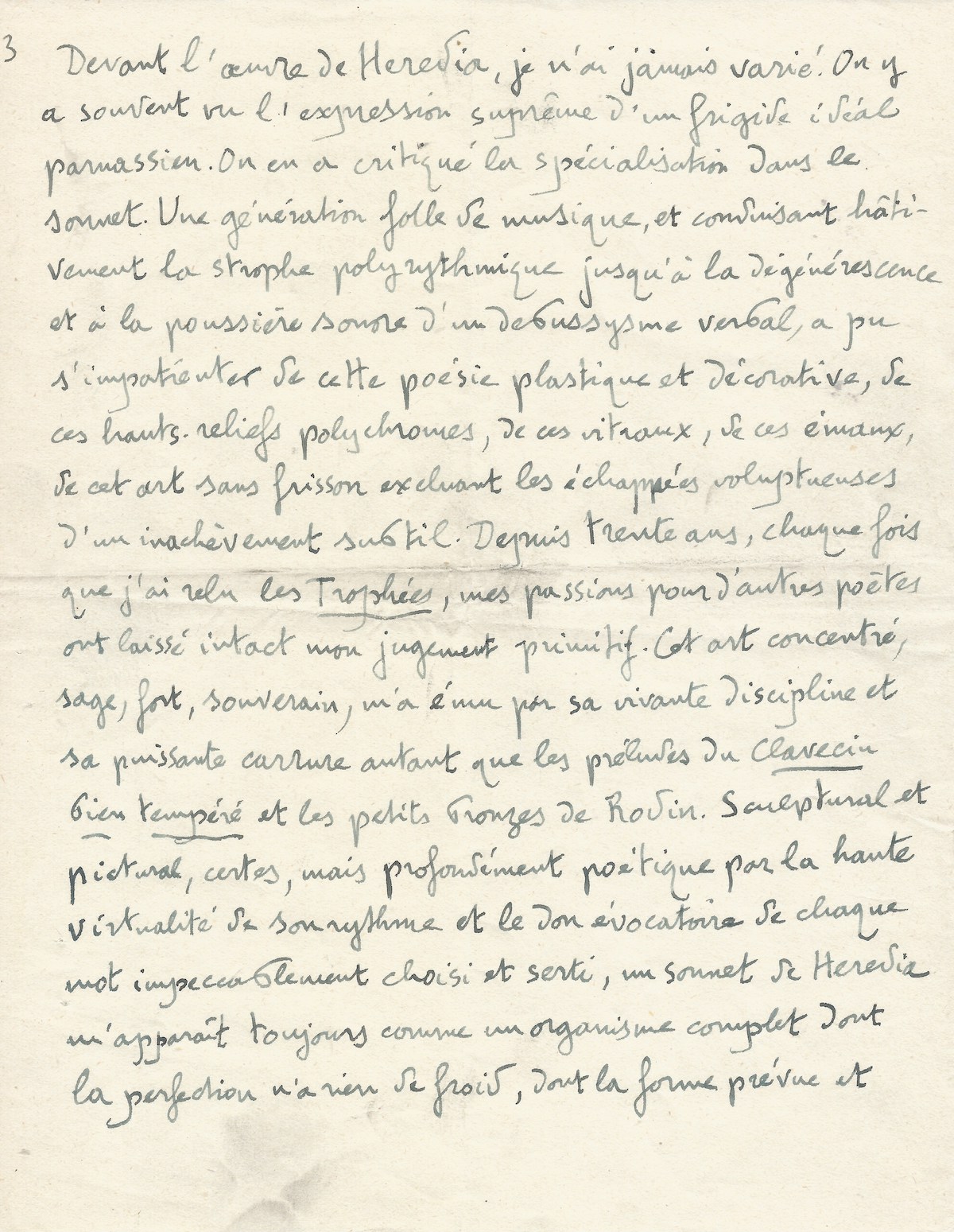

I have often varied in my appreciation of the works. We have crushes, we surf, we leave, we come back. Faced with Heredia's work, I have never changed. It has often been seen as the supreme expression of a frigid Parnassian ideal. The specialization in the sonnet has been criticized. A generation crazy about music and hastily leading the polyrhythmic strophe to the degeneration and sound dust of a verbal debussysm, could have grown impatient with this plastic and decorative poetry, with these high polychrome reliefs, with these stained glass windows, with these enamels, of this art without thrill excluding the voluptuous escapes of a subtle incompleteness.

For thirty years, each time I have reread the Trophies , my passions for other poets have left my primitive judgment intact. This concentrated, wise, strong, sovereign art moved me with its living discipline and its powerful stature as much as the preludes of the Well-Tempered Harpsichord and the small bronzes of Rodin. Sculptural and pictorial, certainly, but profoundly poetic through the high virtuality of its rhythm and the evocative gift of each impeccably chosen and set word, a sonnet by Heredia always appears to me as a complete organism whose perfection has nothing cold , [sic] form absorbs more emotions than it restricts, and which develops in full life with the majesty but also the natural truth of a Poussin order. Never has the word “classic” been able to carry more of an anti-scholastic meaning.

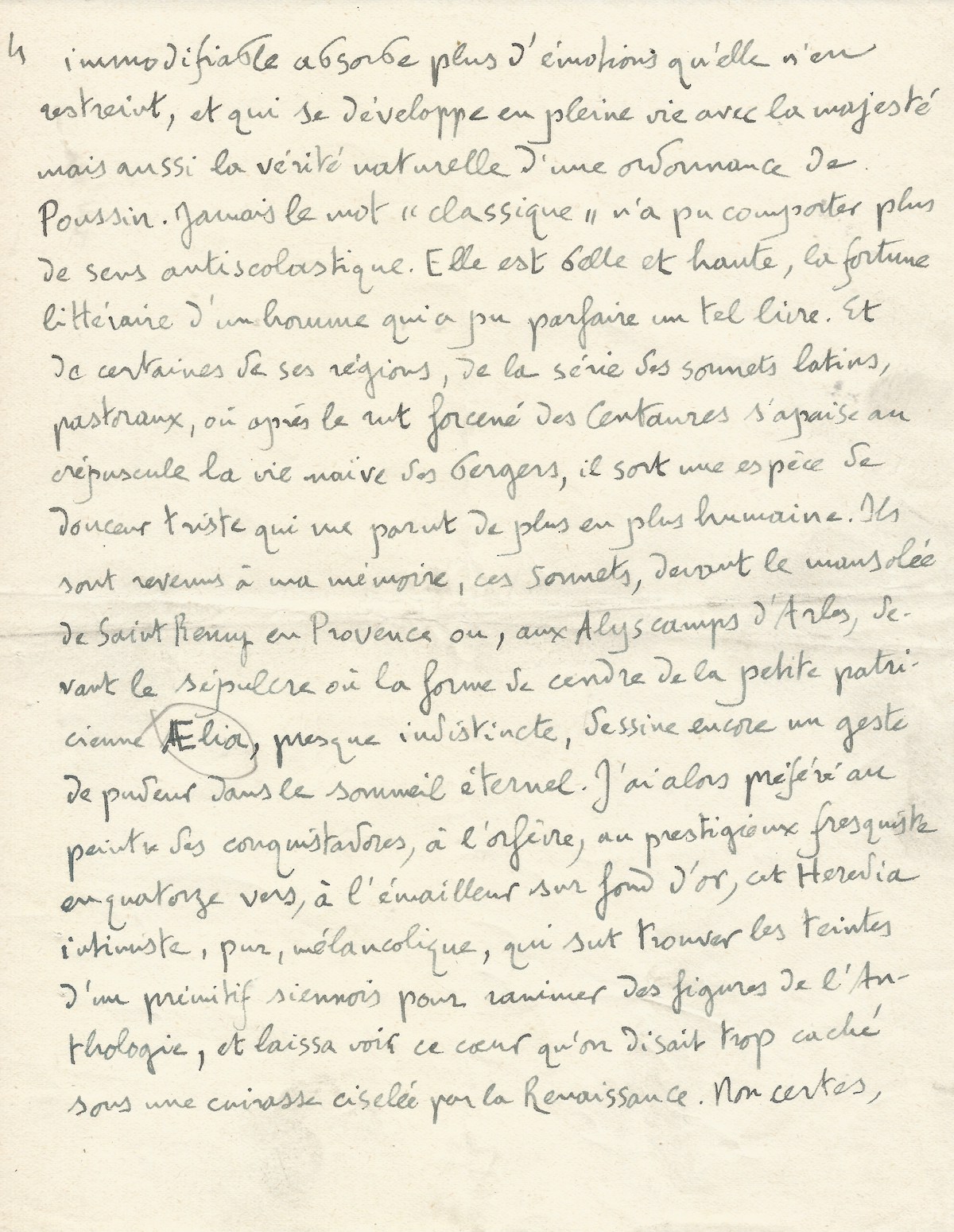

It is beautiful and lofty, the literary fortune of a man who was able to perfect such a book. And from certain of its regions, from the series of Latin, pastoral sonnets, where after the frenzied rut of the centaurs the naive life of the shepherds calms down at dusk, there emerges a kind of sad sweetness which seemed more and more human to me. They came back to my memory, these sonnets, in front of the mausoleum of Saint Rémy in Provence or, at the Alyscamps in Arles, in front of the sepulcher where the ash form of the little patrician Aelia, almost indistinct, still outlines a gesture of modesty in eternal sleep. I then preferred to the painter of the Conquistadores, to the goldsmith, to the prestigious fresco artist in fourteen verses, to the enameler on a gold background, this intimate, pure, melancholic Heredia, who knew how to find the hues of a Sienese primitive to revive figures from the Anthology, and revealed this heart that was said to be too hidden under a armor chiseled by the Renaissance.

No, of course, Heredia ignored nothing of the attractions and magic of sensitivity : he only refused its softness and disorder, and his clarity is complemented by exquisite penumbras and this modeler, this color engraver, this director of monotypes, about whom the praise was especially that applicable to a medalist and a painter, was also capable of enjoying the charms of “pure poetry”. He tasted them in Baudelaire, he appreciated them in Mallarmé, he sensed them in Valéry, and he understood us, the young symbolists, much better than Verlaine did by deifying us.

None of the famous people of that time guessed us like Heredia. But he had firmly chosen the field where he wanted to exercise his creative will, and the sonnet, an embarrassment for us, was his framework, and the spectacle of his slow search for unfixed perfection is admirable. The unfinished works of Heredia, as the piety of Pierre Louÿs has preserved them for us and as the piety of Armand Godoy towards these two deaths now reveals them to us, will give an ever more moving idea of the man and the artist. and higher, completing his moral example. Camille Mauclair »