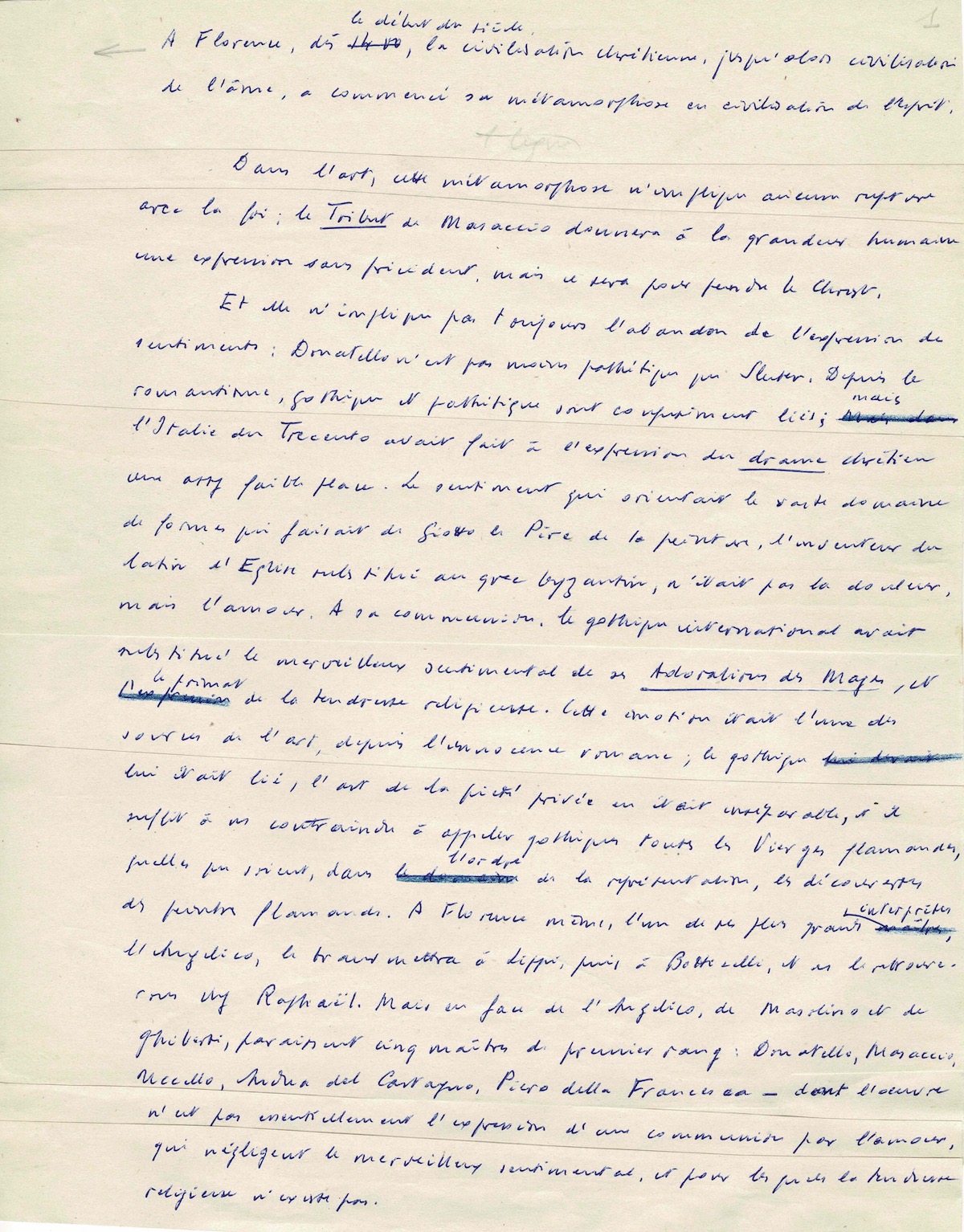

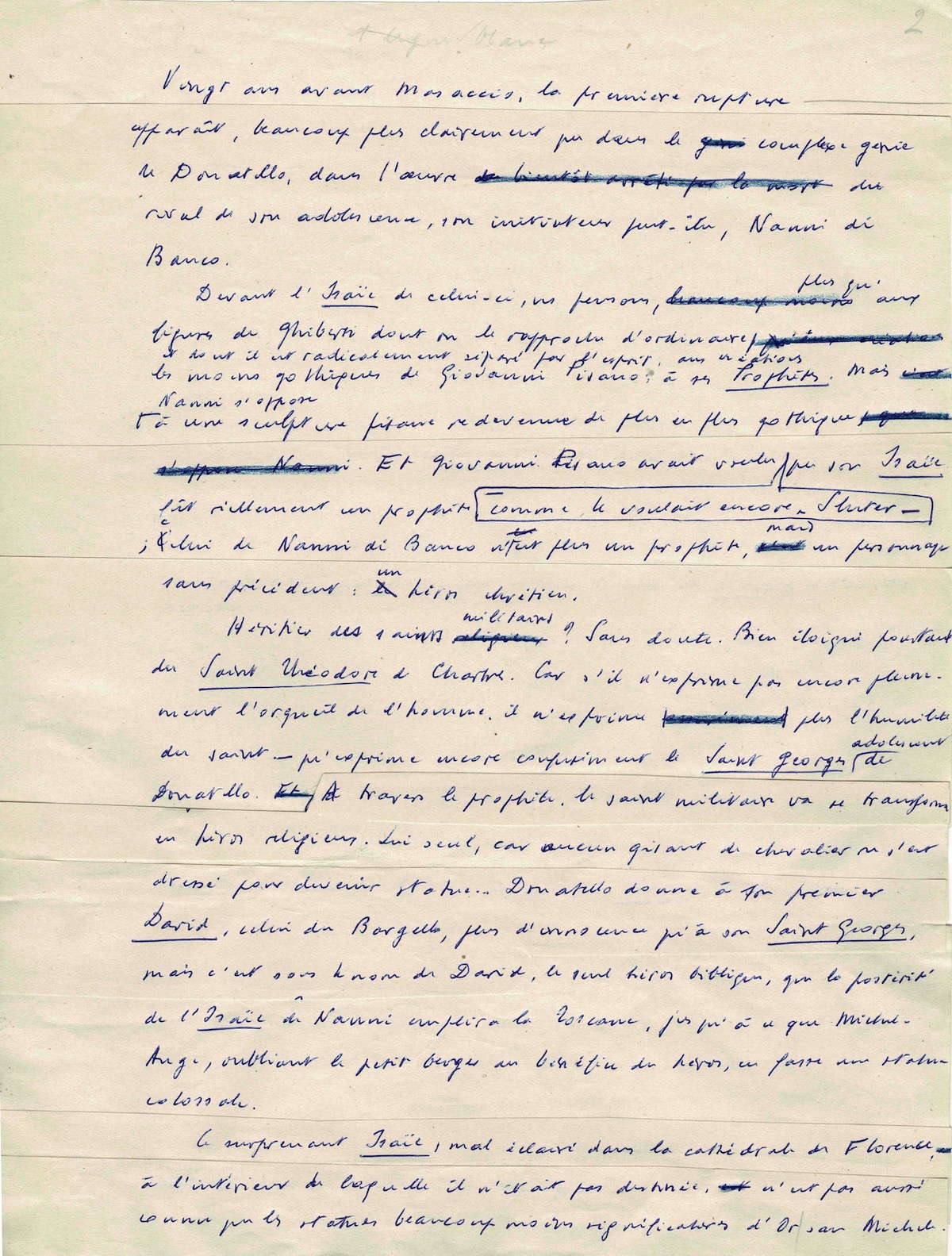

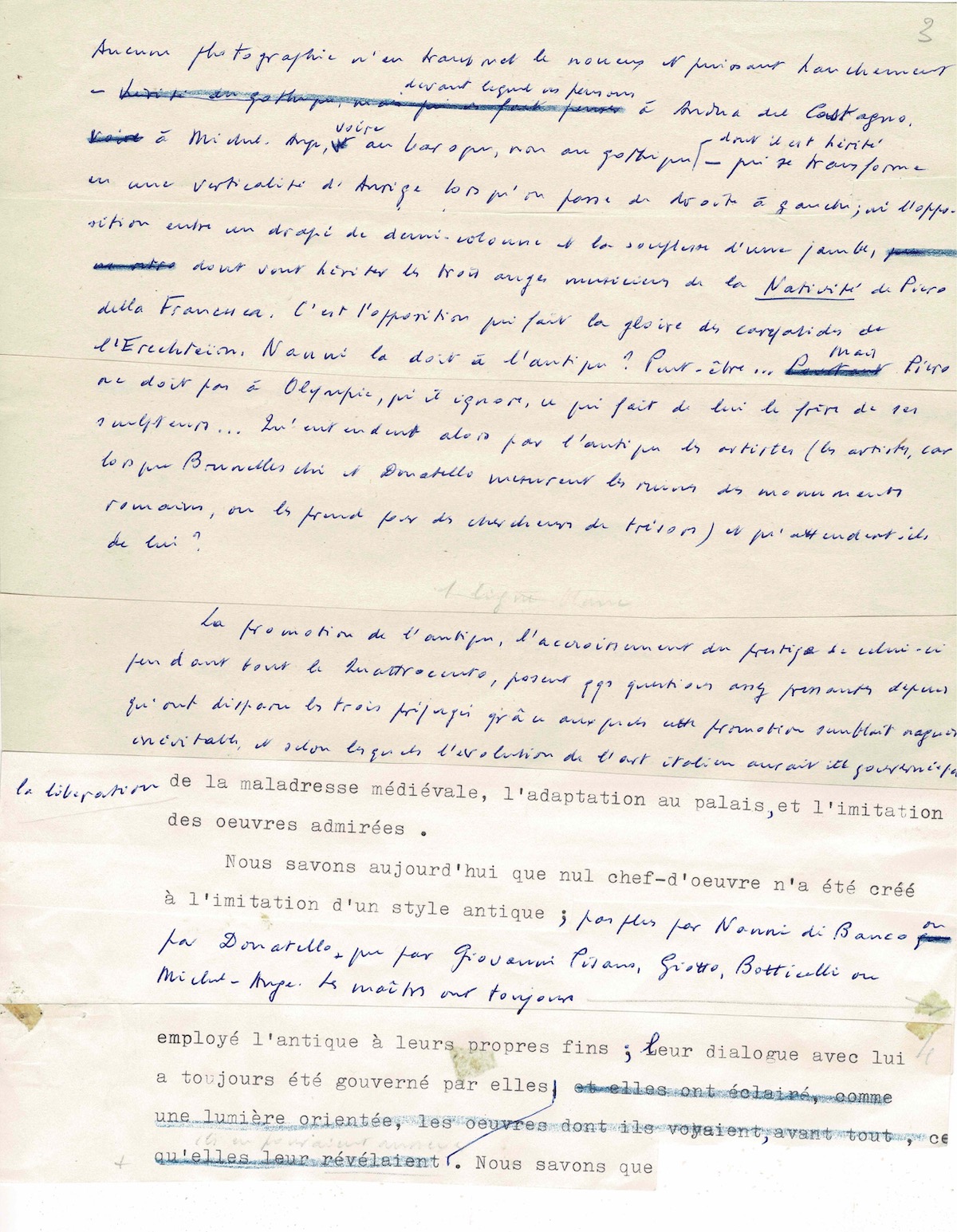

André Malraux (1901.1976)

Autograph manuscript – The beginning of the century.

Three quarto pages with cutouts and montages.

A few typed and corrected lines.

Slnd.

A remarkable working manuscript relating to the Italian Renaissance. Malraux puts into perspective the creations of Giotto, Michelangelo, Raphael, Donatello, Botticelli, Masaccio, etc., analyzing their influences and breaks with the Christian faith.

________________________________________________________________

" In Florence, from 1400 onwards, Christian civilization, until then a civilization of the soul, began its metamorphosis into a civilization of the spirit. In art, this metamorphosis does not imply any break with the faith: Masaccio's Tribute Money [ The Payment of Tribute Money , fresco by Masaccio] will give human grandeur an unprecedented expression, but it will be to paint Christ."

And it does not always imply the abandonment of the expression of feelings: Donatello is no less pathetic than Sluter. Since Romanticism, Gothic and pathos have been inextricably linked ; but Trecento Italy had given rather little space to the expression of Christian drama The sentiment that guided the vast domain of form that made Giotto the father of painting, the inventor of Church Latin replacing Byzantine Greek, was not sorrow, but love. International Gothic had substituted for this communion the sentimental marvel of his Adoration of the Magi , and the format of religious tenderness. This emotion was one of the sacred elements of art, ever since Romanesque innocence; Gothic was bound to it, the art of private piety was inseparable from it, and it suffices to compel us to call all Flemish Virgins Gothic, whatever the discoveries of Flemish painters may be in the realm of representation.

In Florence itself, one of its greatest interpreters, Fra Angelico, would transmit it to Lippi, then to Botticelli, and we will find it again in Raphael. But opposite Fra Angelico, Masolino, and Ghiberti, Donatello , Masaccio, Uccello, Andrea del Cartagno, and Piero della Francesca – whose work is not essentially the expression of a communion through love, who neglect sentimental wonder, and for whom religious tenderness does not exist.

Twenty years before Masaccio, the first break appears, much more clearly than in the complex genius of Donatello, in the work of his youthful rival, perhaps his mentor, Nanni di Banco. When we look at the latter's Isaiah, we think, more than of the lines of Ghiberti, with whom he is usually associated, and from whom he is radically separated in spirit, of Giovanni Pisano's least Gothic creations, his Prophets . But Nanni stands in opposition to a Pisan sculpture that was becoming increasingly Gothic. And Giovanni Pisano had intended, as Sluter still did, that his Isaiah should truly be a prophet; Nanni di Banco's is no longer a prophet but an unprecedented figure: a Christian hero.

Heir to the military saints? Undoubtedly. Yet quite different from the Saint Theodore of Chartres. For if he does not yet fully express the pride of man, he no longer expresses the humility of the saint—which Saint George . Through the prophet, the military saint will be transformed into a religious hero. He alone, for no recumbent knight has risen to become a statue. Donatello gives his first David , the one in the Bargello, more assurance than his Saint George , but it is under the name of David, the only biblical hero, that the posterity of Isaiah will fill Tuscany, until Michelangelo, forgetting the young George in favor of the hero, makes him a colossal statue. […]

The promotion of antiquity, and its increasing prestige throughout the Quattrocento, raise some rather pressing questions since the disappearance of the three prejudices that once made this promotion seem inevitable, namely that the evolution of Italian art was governed by the liberation from medieval clumsiness […]

We know today that no masterpiece was created in imitation of an ancient style; not by Nanni di Banco or Donatello, nor by Giovanni Pisano, Giotto, Botticelli, or Michelangelo … »