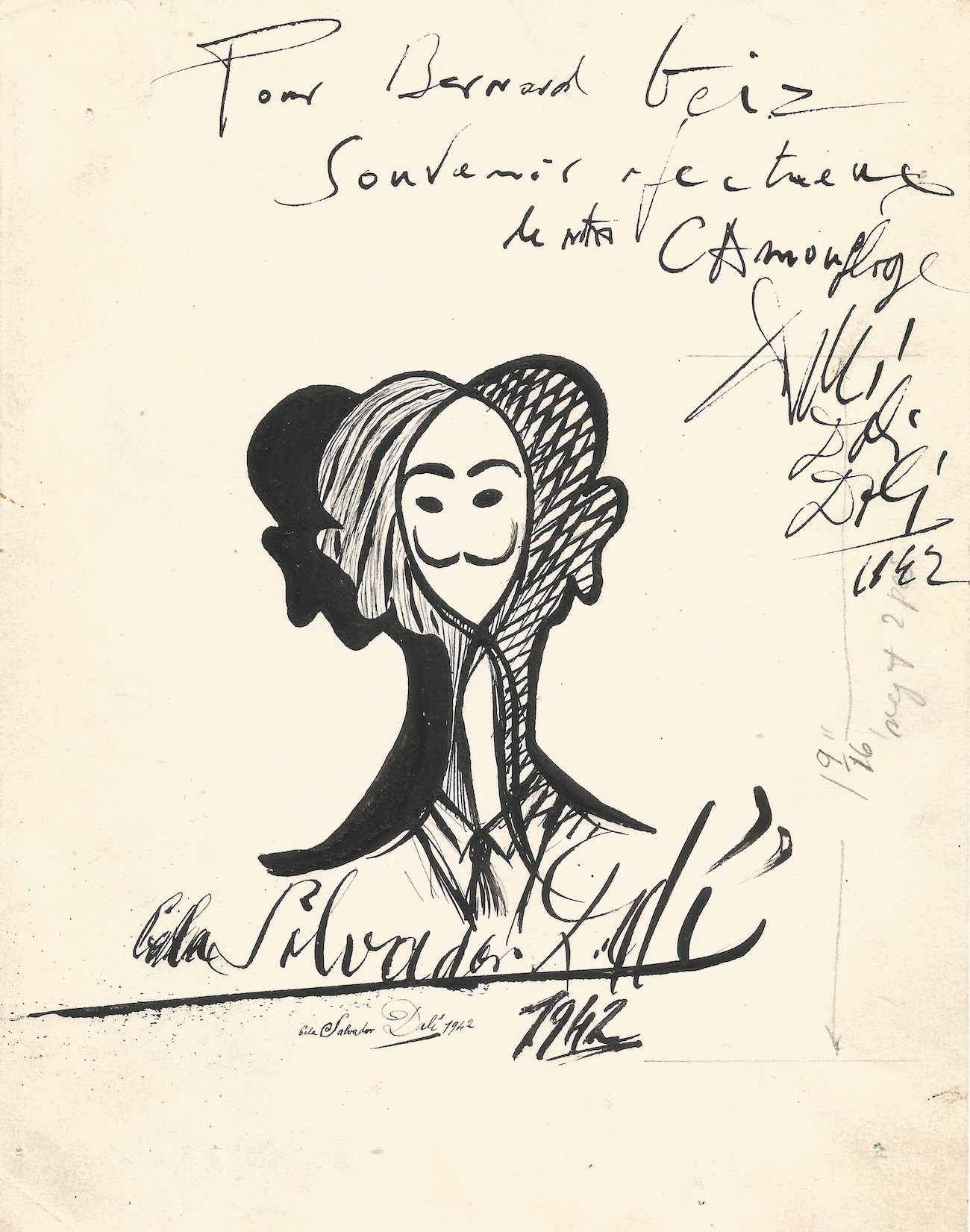

Salvador Dali (1904.1989)

Original signed drawing – Camouflage – Self-portrait – Garcia Lorca.

Indian ink on strong paper.

Signed five times by Dalí and dedicated to Bernard J. Geis, publisher of Esquire Magazine.

For Bernard Geiz Affectionate memory of our camouflage

Dalí Dalí Dalí 1942

Salvador Dalí Gala Salvador Dalí Gala 1942

Federico García Lorca in the background .

Certificate of authenticity from MM. Nicolas and Olivier Descharnes. The work is recorded in the Descharnes Archives under the reference d1273.

Dimensions 170 x 132 mm.

Handwritten annotations on the back.

Tiny pinholes in corners. Remarkable general condition otherwise.

“Do your eyes have it?

The answer will undoubtedly seem obvious: the mask with long mustaches pointing towards the sky, the mandorla-shaped face which is outlined with generous strokes of Indian ink… “It’s Dalí of course! », the Spanish prodigy, the king of surrealism. That's right ; in part at least: this fantastic drawing is in fact a rare self-portrait drawn by the eccentric Catalan. Not only that, we will see it…

This drawing was produced – and published – on the occasion of the publication in the American magazine Esquire [i] , in August 1942, of an important article written by Dalí: Total Camouflage for Total War . Over four illustrated pages, Dalí tells readers, while the Second World War rages, the strategic importance of camouflage, of understanding images and their reality, illusion and truth. In the middle of the article (page 130) [ii] , our drawing is represented at the top of an insert “ A portrait of Salvador Dalí ” in which Dalí answers some questions presented in the form of a Proust questionnaire.

In December 1942, Esquire republished this self-portrait at the top of an article by Raymond Gram Swing, Nativity of a New World , relating to Dalí's painting.

In this context of creation, at the center of a file devoted to hidden images, how can we imagine that an artist so facetious, so imaginative, so inventive was satisfied with this drawing of a simple silhouette to represent himself? We must therefore look at this drawing with more attention, look at the hidden symbolism, to answer the question suggested by Dalí “ Do your eyes have it?”

To try to understand the image, let's look at the text next to it. In the middle of the Second World War, Salvador Dalí launched the challenge of psychologically controlling the enemy's vision. Controlling vision would ensure the triumph of one side over another.

In this article from August 1942, Dalí teaches us how Cubism invented, according to him, camouflage. His story makes Picasso the official inventor of human camouflage. He attributes to his compatriot the following words: “ If you want to make an army invisible, you just need to dress the soldiers like harlequins ” [iii] . And Dalí explains “ that an image can be made invisible – without transformation – simply by surrounding it with other images which make the viewer believe that he is looking at something else ”. His point is illustrated by several works in which the magic of illusion triumphs. This is the whole secret of the painter explained here, who took advantage of a “ paranoid mind ” to see what the eyes of ordinary mortals could not grasp. “ The discovery of invisible images was certainly part of my destiny.” Following the precepts of Aristophanes and da Vinci, observer of mimetic and natural camouflages in animals, the painter plays with illusion, encouraging an immoderate use of the systematic delirium of interpretation.

Now let's return to our drawing. It is with Dalí's surrealist eyes, in the light of this article, that we must reconsider this self-portrait. It undoubtedly hides another meaning, another image: it is a camouflage. This is also the meaning of the dedication! On closer inspection, certain details are striking, sticking too closely to the text to be nothing more than coincidences. The hash of the straight silhouette drawing regular diamonds is not accidental: it is the Harlequin costume, the first of the camouflaged, the one that Picasso is rightly talking about. The silhouette to the left of the mask is spotted: it is tiger fur, which, in the words of Dalí in this same Esquire article, is a model of camouflage and illusion.

To complete the analysis, it seems appropriate to compare our drawing to several other works by Dali represented below: The self-portrait splitting into three (Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí , Figueres, cat. P191) , the Self-portrait separating into three Harlequins (Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí , Figueres, cat. P1015) and Harlequin ( Museo de Arte Contemporáneo AS 07488 ).

Drawing on the experiences of Cubism, Dalí assumed the multiplication of points of view, which he favored over rational three-dimensionality, to leave a greater role to the imagination. By using colors that are not mimetic of reality here, Dalí sets up a system of thought which will lead in the 1940s to this discourse on camouflage and paranoid vision.

Federico Garcia Lorca . This drawing, although clear at first reading, in truth reveals several symbolisms, as we have seen: camouflage, illusion, magic, splitting, cubism, nature, etc. Yet one last face is hidden there! A black silhouette, discreetly positioned in the background: that of Federico García Lorca [iv] , the Spanish friend, the brother, the legendary poet shot in August 1936 by the Francoists.

We will not return to the passionate and historical friendship between Lorca and Dalí, “ An erotic and tragic love, due to the fact of not being able to share it ” [v] ; However, we must be amazed to see Dalí accompany his own image with the eternal and benevolent shadow of Lorca, his soul brother who died six years earlier.

Previously ignored in the Dalinian archives and in a private collection since its creation in 1942, this drawing now, for all the reasons mentioned above, fuels the myth of the master of Port Lligat.

Finally, we will repeat the words of N. Descharnes upon the discovery of this treasure: “ This drawing is historic! »

[i] We attach the two Esquire from August and December 1942.

[ii] For publication in Esquire , the drawing was cropped and Dalí's dedication erased. We can see in the right margin of our drawing pencil annotations, from another hand, traces of this layout.

[iii] It was the painter Guirand de Scévala who apparently first had the idea of hiding canons by exploiting the Cubist aesthetic. His research on the relationship between form and light and their mutual distortion. The colorful canvases in the colors of the surrounding countryside made the weapons imperceptible. In the summer of 1915, the “trompe-la-mort” unit was born. Made up of 125 reservists, building workers and painters, it recruited carpenters, carpenters, mechanics and other tradespeople. Happy to leave the hell of the trenches, a large number of artists joined the ranks. André Mare, Fernand Léger, Georges Braque and many others joined the section. Together they created fake plants, rocks, humans, railway tracks... and masks!

[iv] See the work Invitacio a la Son (Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí , Figueres, cat. P172). The Descharnes Archives also keep a similar drawing, made in 1944, depicting Dalí and Lorca, under the reference d6344

[v] Letter from Salvador Dalí, about Lorca, to the newspaper El País in 1986.