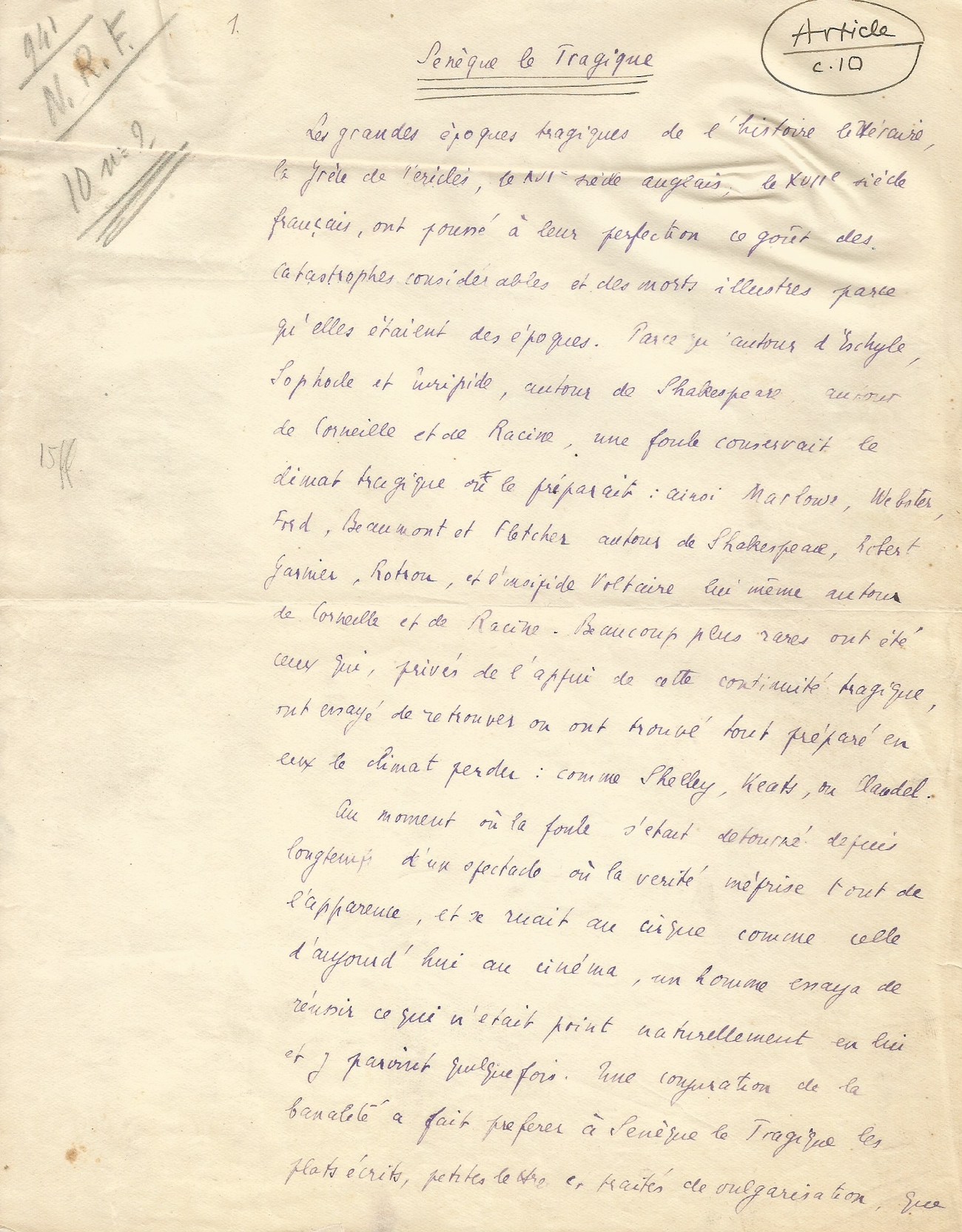

Robert BRASILLACH (1909.1945)

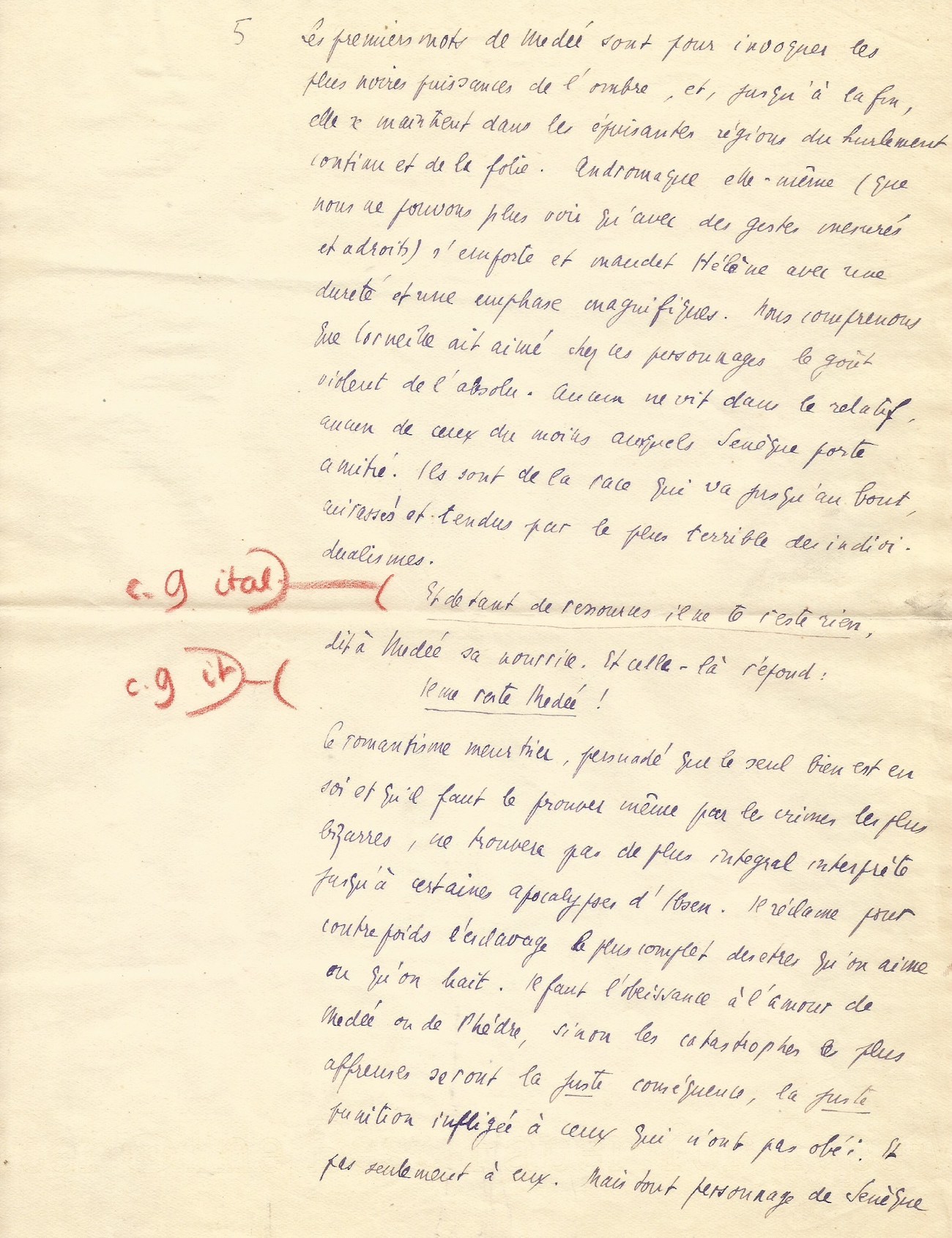

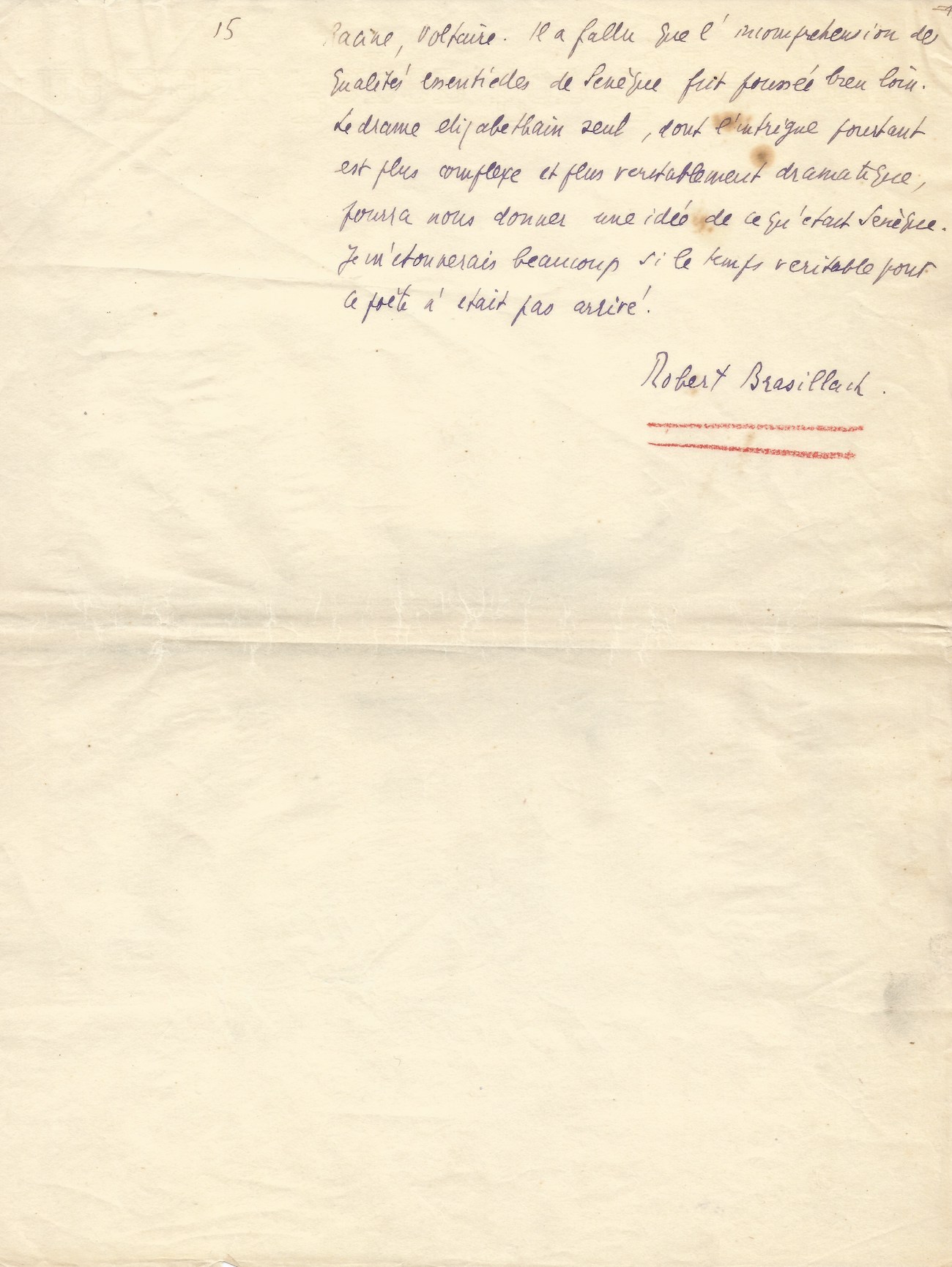

Autograph manuscript signed – Seneca the tragic.

Fifteen pages large in-4° in purple ink. Slnd (1931)

“I would be very surprised if the true time for this poet had not arrived. »

Very beautiful manuscript by Brasillach testifying to his admiration for Seneca and his awareness of nature. This manuscript was published by the Nouvelle Revue Française in 1931.

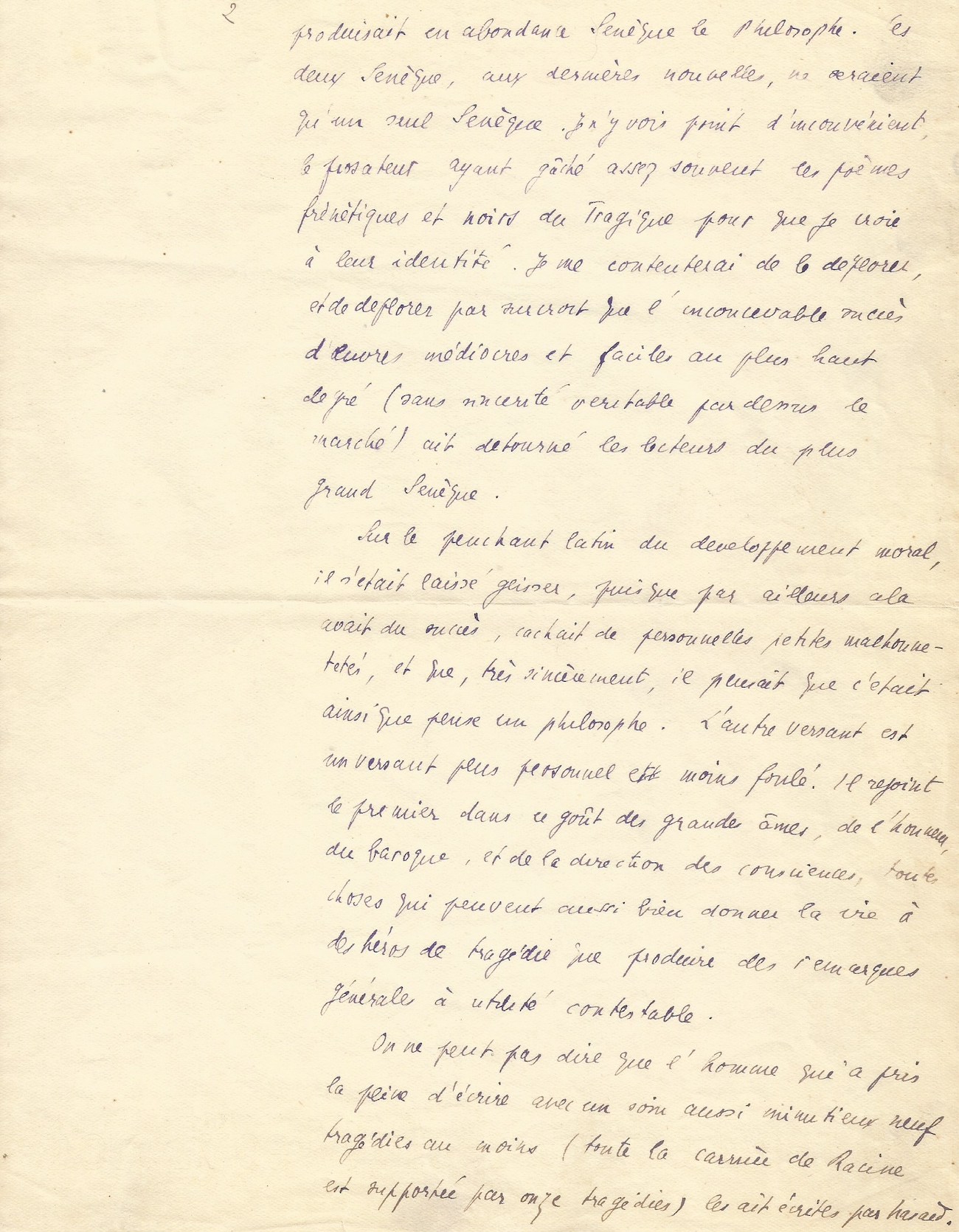

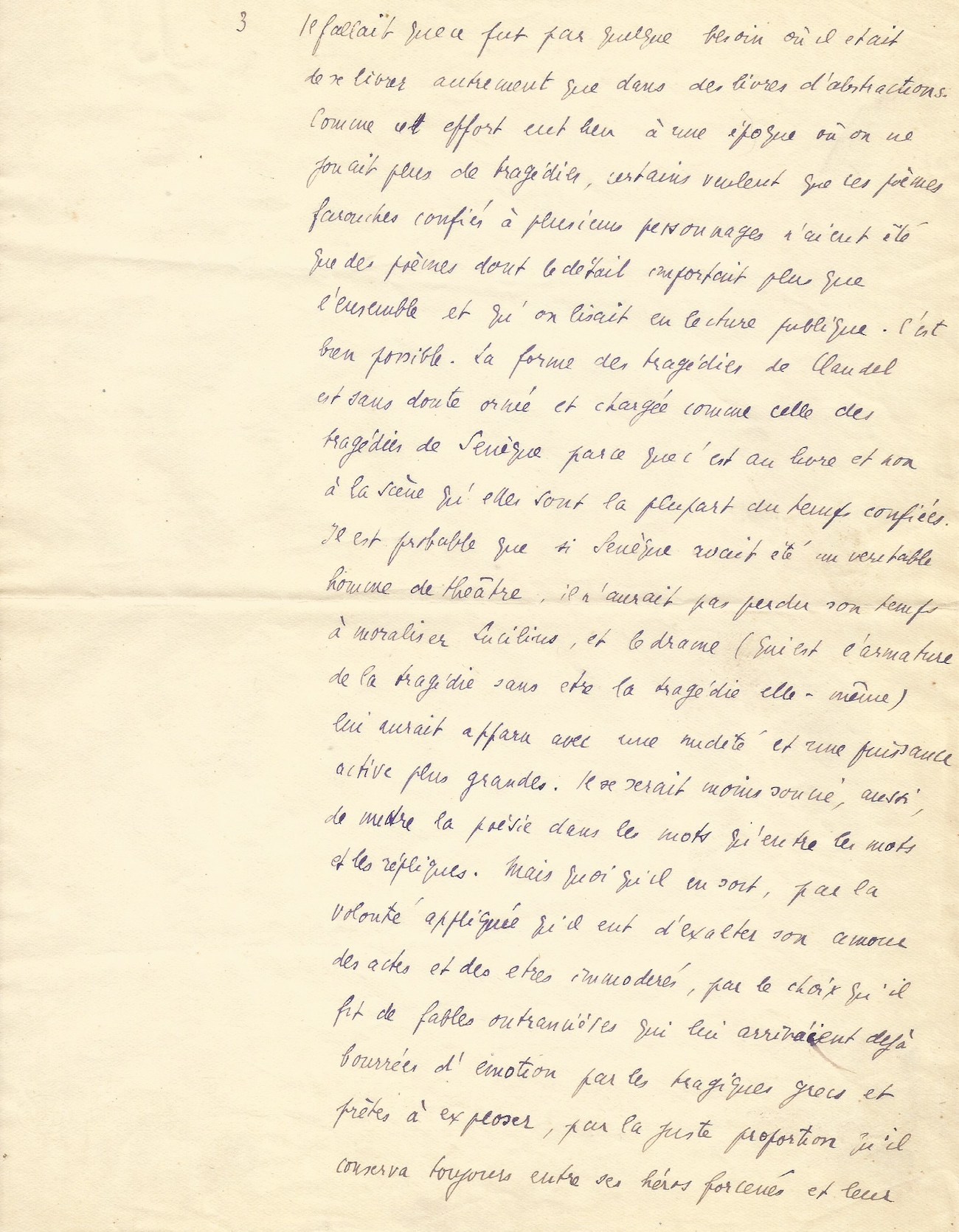

“ Seneca the Tragic. The great tragic eras of literary history, the Greece of Pericles, the English 16th century, the French 17th century, brought to their perfection this taste for considerable catastrophes and illustrious deaths because they were epochs. Because around Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, around Shakespeare, around Corneille and Racine, a crowd preserved the tragic climate and prepared it: thus Marlowe, ...., Beaumont and Fletcher around Shakespeare, Robert Garnier, ..., and the insipid Voltaire himself around Corneille and Racine . Much rarer were those who, deprived of the support of this tragic continuity, tried to rediscover or found the lost climate fully prepared within themselves: like Shelley, Kets, or Claudel. At the moment when the crowd had long since turned away from a spectacle where truth disregards all appearance, and rushed to the circus like today's at the cinema, a man tries to achieve what was not not naturally in him and sometimes succeeded. A conjuring of banality made Seneca prefer the tragic to written dishes, small letters in popular treatises, which Seneca the philosopher produced in abundance. The two Senecas, according to the latest news, are only one Seneca... having spoiled the frenetic and dark poems of the Tragic often enough for me to believe in their identity. I will content myself with deploring it and also deploring that the inconceivable success of mediocre and easy works of the highest degree has turned readers away from the greatest Seneca. On the Latin leaning of moral development, he had let himself slide, since moreover it was successful, hid small personal dishonesties, and (…) he thought that this was how a philosopher thinks. The other side is a more personal and less crowded side. He joins the first in the taste for great souls, for the honor of the baroque, and for the direction of consciences, all things which can give life to heroes of tragedy as well as produce general remarks…. We cannot say that the man who took the trouble to write at least nine tragedies with such meticulous care (Racine's entire career is supported by eleven tragedies) wrote them by chance. (…) It had to be out of some need to indulge in something other than books of abstractions. As this effort took place at a time when tragedies were no longer being performed, some believe that these fierce poems entrusted to several characters were only poems whose detail was more important than the whole and which were read in public reading. . The form of Claudel's tragedies is undoubtedly decorated and loaded like those of Seneca's tragedies because it is to the book and not to the stage that they are most of the time entrusted. It is probable that if Seneca had been a true man of the theater, he would not have wasted his time moralizing Lucilius and the drama (which is the framework of the tragedy without being the tragedy itself) would have appeared to him with a nudity and greater active power. By the diligent desire he had to exalt his announcement of immoderate acts and beings, by the choice he made of outrageous fables which arrived to him already full of emotion from the Greek tragedians and ready to explode, by the just proportion that he always maintained between his frenzied heroes and their language several degrees more frenzied, he found himself having grasped on the fly, several times, the tragic spirit and thus being the only representative of value between Euripides and the 16th century.

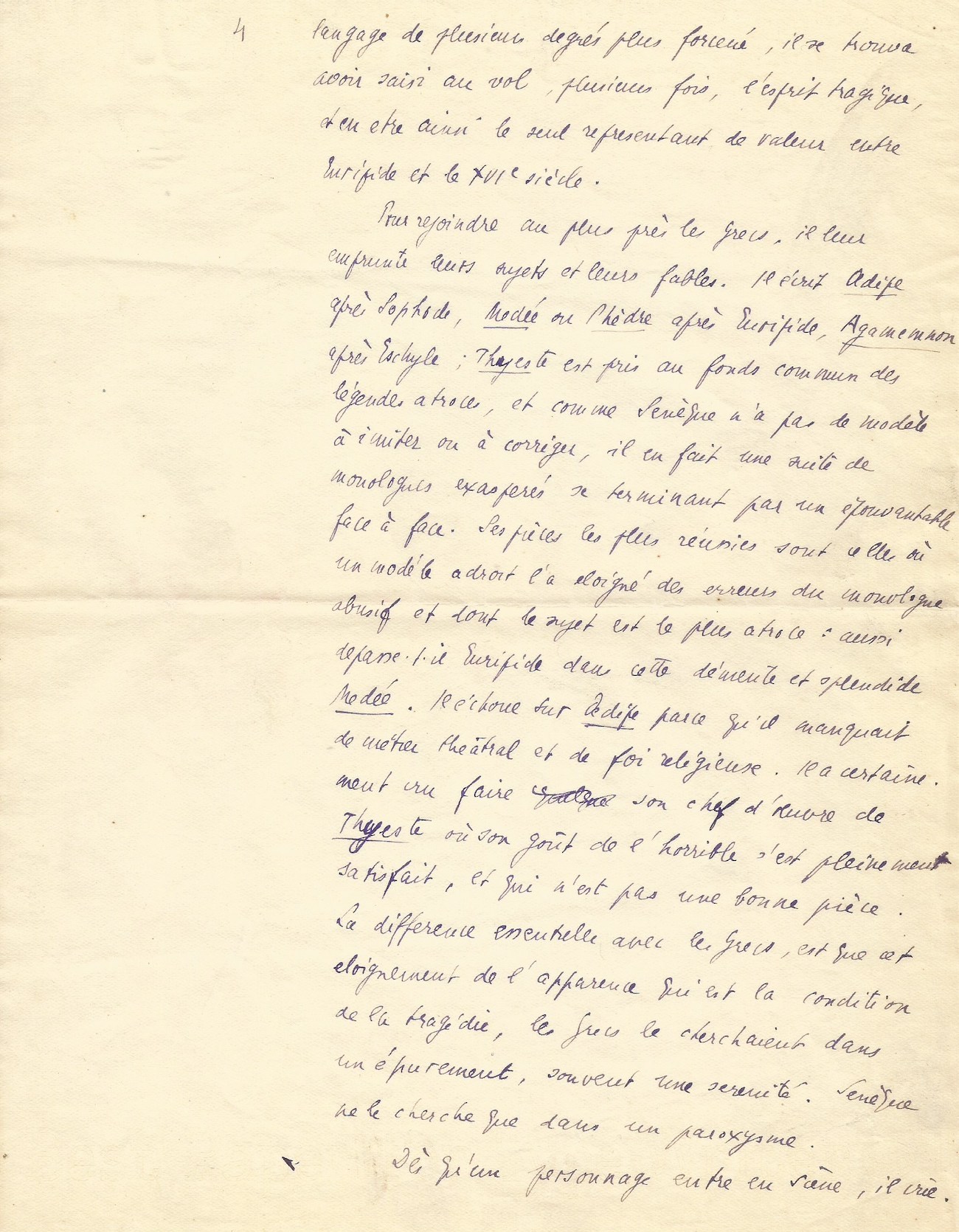

To reach the Greeks as closely as possible, he borrows their subjects and their fables. He writes Oedipus after Sophocles, Mede or Phaedra after Euripides, Agamemnon after Aeschylus, Thyestes is taken from the common stock of legends and as Seneca has no model to imitate or correct, he makes a series of exasperated monologues ending by a terrible face to face. The most successful plays are those where a skillful model has distanced him from the errors of abusive monologue and whose subject is the most atrocious: he therefore surpasses Euripides in this demented and splendid Medea . He fails on Oedipus because he lacked theatrical craft and religious faith. Thyest masterpiece where his taste for the horrible was fully satisfied and which is not a good piece. The essential difference with the Greeks is that this distance from appearance which is the condition of tragedy, the Greeks sought it in a purity, often in a serenity. Seneca only seeks it in a paroxysm. As soon as a character enters the scene, he screams. Medea's first words are to invoke the darkest powers of the shadows and she maintains herself in the exhausting regions of continuous screaming and madness. Andromache herself (…) loses her temper and curses Helen with magnificent harshness and emphasis? We understand that Corneille liked the violent taste for the absolute in these characters. None lives in the relative, none at least of those whom Seneca is friendly with. They are the race that goes to the end, armored and tense by the most terrible of individualisms. (…) This murderous romanticism, that the only good is in oneself and that it must be proven even by the most bizarre crimes, will not find a more complete interpreter until certain apocalypses…. As a counterweight, he demands the most complete slavery of the beings we love or hate. Obedience to the love of Medea or Phaedra is necessary, otherwise the most terrible catastrophes will be the just consequence, the just punishment inflicted on those who have not obeyed. But every character in Seneca (p6) is like the God who punishes up to the third and fourth generation. No one wants to die alone. (…) no one understood the dictatorship of passion better than Seneca. Are we still surprised that he had Nero as a student? (…) to their own royalty, they then throw themselves furiously at the other end and demand servitude with voluptuous and noisy humility. With what gentleness, what carnal languor, Phèdre refuses the name mother: “The name mother is too superb and too powerful, it is a more humble name which suits our feelings” (…) Seneca’s characters are intelligent. The characters of tragedy, unlike those of drama, are almost always intelligent. They know what they are and analyze it with indescribable joy, the joy of clear consciousness. Through this intelligence, Seneca is closer to us than Sophocles because he perhaps knew all the feelings that we believe we invented. The sickly, almost sadistic taste for pity, it was not Russian novels that first brought it into fashion. (…) To the nurse who tells him that Hercules will no longer love Iole now that she is a slave, Deianira responds in admirable verses: “The love of Hercules is only more inflamed by his misfortunes, he loves precisely because she is deprived of her home (…) This is what, at the moment when Seneca's heroes were definitely going to become caricatures of Pierre Corneille or Hugo, tips the balance towards life. In the midst of the excesses of a passion pushed to its limits and driven to madness, a survival of the classic spirit restores them to the essential lucidity. Phèdre, in the rather mediocre play which bears her name, has none of the intoxicating, dangerous beauty of the Racinian heroine.

It's too easy prey that a Freudian psychologist wouldn't want. But a very original and very strong scene saves the drama: it is the one where the intelligent Phèdre overcomes her unbridled desire and uses all her means to make Hyppolyte give in. The scene of the declaration is so beautiful, with its blend of intelligence and sensuality, that Racine took it up line for line. Yet if these men and women eternally in pursuit of an unbridled ideal can seduce modern minds, this is only one of the least merits of Seneca's theater. (…) The essential thing is that Seneca the tragic was a very great poet and that, like the greatest, like Aeschylus, Shakespeare or Baudelaire, he was joined to the world by mysterious links and knew that the main inspirations of a poem are the spirits of the earth. This poetic truth is found in every great tragedy, the Greeks and Racine leaned more particularly towards the gods and fate, Shakespeare towards the demons of the sensible universe. This background, which we will call religion, is what essentially differentiates tragedy from drama, with the distance between the characters. She is at Claudel's. Corneille sometimes misses her. Seneca did not believe in gods. I don't know of any plays, except Macbeth, where the presence of nature is more visible than in his. The long monologues which open each of these tragedies place it first in a universe where it is hot or cold, where the stars shine, where the sky is hidden under black smoke, where the river runs, where the meadows tremble under the wind. (…) Macbeth can only maintain its supernatural atmosphere because we constantly talk about trees walking, owls hooting, nocturnal birds waking up and all the beasts of the night, all the evil powers of the earth surround the drama and collaborate in it. (…) Les Troyennes is an admirable piece entirely dominated by the high flames of Troy and the sound of the ships setting sail. And these are not easy metaphors for literary criticism. (…) And in this poetic work, Seneca is served by a very beautiful language. The essential characteristics of Latin genius in the construction of these sentences are almost not found there: they are accumulations, juxtapositions rather than a sequence. But this simplified syntax only serves to highlight the word which becomes the master of the sentence. Not so much the rare word as the simple but striking word, the shock word. I would pity those who would not be able to discover in the terrible terms with which this barbaric style is full, in the false jewels, in red, and all the illuminations with which this savage is so colorful, an extraordinary living and poetic force. (….) but this faith in the spirits of the earth, which gives Seneca's “religion” its most disturbing, most poisonous poetic force, is still combined with a taste for death and nothingness that is an admirable thing. The Greeks put behind all their dramas the shadow of a fatality in which Seneca no longer believes.

He allows unconscious forces to hover around human tragedies, but he does not want a God or personal Gods to take sides and judge. However, tragedy does not exist without religion, he puts death in place of the gods. He blames the despair of the drama, now without a solution: he closes all the doors of the cage where his terrible prisoners are agitated and refuses them the escape of another life. (…) And this easy philosophy of nothingness, easy when it is taken for an original philosophy and ready for development, is a dramatic means of extraordinary emotion. Likewise, Hamlet's famous monologue is only a series of commonplaces but takes on its full value when it is placed in the drama and the atmosphere, because it is placed in the drama and the atmosphere, because It is the sincere and terrified complaint of a man who is afraid of what comes next. Seneca's heroes are not afraid of what happens after death. They throw themselves into it without fear, invoking it as liberating, as the port finally found. One of them, somewhere, despises the one who does not know how to die. But it is not only the contempt of cowardice, it is the contempt, almost pity, that we have for the one who ignores the greatest of good things, who does not like death. And these two sacred elements, nature and death, merge into a religious enthusiasm for everything that is not religion. Thus Lucretius celebrated sacrifices in honor of human reason. A purely romantic doctrine, the exaltation of the individual and the exaltation of the unconscious forces of nature, comes to replace religion. From there undoubtedly a sometimes primary faith in reason and progress, but also, above all, combined with the superhuman pride of these heroes wrapped in their great crimes, a supernatural power which passes from the gods to man. While, in religions, supernatural and magical power follows from nature to man, necessarily passes through the gods and is captured without return by them in passing, in the mysticism of Seneca, magical power flows quite naturally and without intermediary from nature to man who replaces the gods. Hence these incantations which are only the translation into ceremonial language of the well-known relationships which exist between the world and us. Hence these prophetic appearances, this divinatory sense that man has taken from the gods. The characters, those of the chorus, affirm at each moment in a mysterious tone the confidences that the universe has made to them. “ and there will come in future years, the times when the ocean will loosen its bonds, when an immense land will extend it, when the queen of the seas will then discover the New World, and it will no longer be Iceland, the last Earth ! » It's beautiful to discover America in the year 60! It is curious to think that the fortune of this poet was as extraordinary as his talent. We know that French tragedy, this drama (…) where the chorus disappears very quickly, came from Seneca the Tragic. That Corneille was admired, for all his rocky and Spanish genius, is not surprising. That Racine loved intelligence and passion there is very likely. But that the very technique of French tragedy, this skillful and slow progression, skillful and almost always discreet characters, came out of this colorful, breathtaking and barbaric drama, that is what I cannot understand. Nature, which holds an immense place in Seneca's work, the taste for death, all this has disappeared from the almost purely human play of passions staged by..., Corneille, Racine, Voltaire. The misunderstanding of Seneca's essential qualities had to be pushed very far. Only the Elizabethan drama, whose plot is more complex and more truly dramatic, will be able to give you an idea of what Seneca was. I would be very surprised if the true time for this poet had not arrived. Robert Brasillach »