René Descartes (1596-1650)

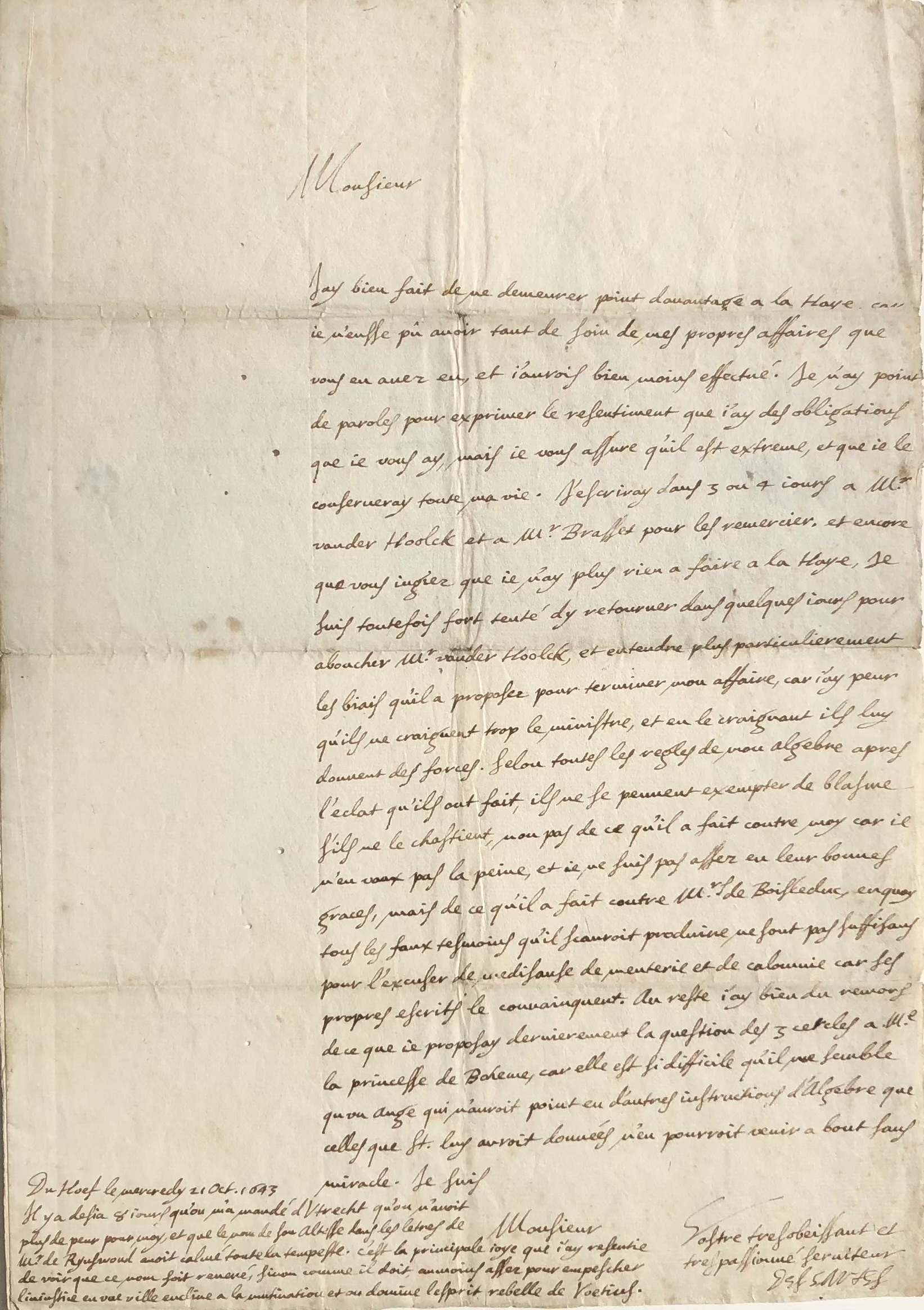

Autograph letter signed and addressed to Mr. Alphonse de Pollot, Gentleman of the Chamber to His Highness in The Hague.

One folio page. Autograph address and wax seal residue on the 4th leaf .

Egmond aan den Hoef, October 21, 1643.

"Besides, I deeply regret having recently proposed the question of the three circles to the Princess of Bohemia."

A long letter from René Descartes thanking his friend Pollot for his support in the Utrecht dispute: he vilifies Voetius, the Protestant enemy, and mentions one of his mathematical theories, the circle theorem, the precursor to Descartes' Theorem .

________________________________________________________

“Sir, I was right not to remain any longer in The Hague, for I could not have attended to my own affairs as you have, and I would have accomplished far less. I have no words to express the resentment I feel for the obligations I owe you, but I assure you it is extreme, and I will retain it all my life . I will write in three or four days to Mr. vander Hoolck and Mr. Brasset to thank them. And even if you judge that I have nothing more to do in The Hague, I am nevertheless very tempted to return there in a few days to speak with Mr. vander Hoolck, and to hear more specifically the means he has proposed to resolve my matter, for I fear that they are too afraid of the ministry, and in fearing it, they are giving it strength .” According to all the rules of my algebra, after the uproar they caused, they cannot escape blame. If they do not punish him , not for what he did against me, for I am not worth the trouble, and I am not sufficiently in their good graces, but for what he did against the Lords of Bois-le-Duc, in which all the false witnesses he could produce are not sufficient to excuse him from slander, lies, and calumny, for his own writings convict him. Moreover, I have much remorse for having recently proposed the question of the 3 circles to the Princess of Bohemia , for it is so difficult that it seems to me that an angel who had no other instructions on Algebra than those given to him by St. [Stampioen?] , could not accomplish it without a miracle.

I am, Sir, Your most obedient and most passionate servant, Descartes. [Egmond] Du Hoef, Wednesday, October 21, 1643

Eight days ago, I received word from Utrecht that there was no longer any fear for me, and that the name of His Highness, in the letters of Mr. de Ryusmond, had calmed the entire storm. This is the greatest joy I have felt, to see that this name revived, if not as it deserves, at least enough to prevent injustice in a city prone to mutiny and where the rebellious spirit of Voetius reigns .

________________________________________________________

A precious autograph letter signed by René Descartes offering a fascinating glimpse into the Utrecht Quarrel opposing him to his enemy Voetius, and into Cartesian mathematics relating to the "question of the three circles".

Having settled in Holland in 1629 to freely pursue his research and publications, René Descartes was, from 1641 onwards, subjected to relentless attacks by Voetius, who accused him of atheism. This "Utrecht Controversy" escalated to such a degree that the philosopher appealed to the French ambassador for his defense. Descartes was condemned by the University of Utrecht on March 17, 1642, which forbade any writing for or against him. If we are to believe the postscript to this letter, by October 21, 1643, the matter had been settled eight days earlier: " I have been informed from Utrecht that there is no longer any fear for me, and that the name of His Highness, in the letters of Mr. de Ryusmond, has calmed all the storm." "This is the principal joy I have felt, to see that this name revived, if not as it should be, at least enough to prevent injustice in a city prone to mutiny and dominated by the rebellious spirit of Voetius. "

Pollot had defended the philosopher in this bitter quarrel, for which the latter warmly thanked him: " I have no words to express the resentment I feel for the obligations I owe you, but I assure you it is extreme, and I will retain it all my life."

Born into a Protestant family from Piedmont who sought refuge in Geneva in 1620 to escape persecution by the Duke of Savoy, Alphonse de Pollot (1604-1668) soon after settled in Holland with his brother. He pursued a career in the army and at court. From March 1642, he was a gentleman of the chamber to His Highness the Prince of Orange. He was one of the philosopher's closest friends, who readily received him in what he called his "hermitage."

Gijsbert Voet, also known as Gisbertus Voetius (1589-1676), Lutheran rector of Utrecht University (founded in 1636) and holder of the chair of theology, was at the root of the philosopher's troubles. A fanatical proselytizer of Protestant orthodoxy, he denounced Descartes's insidious atheism through " slander, lies, and calumny," also accusing him of supporting Copernicus's heliocentric theories.

The Utrecht Controversy – The censorship of thought by the Protestant religion – the struggle of faith against the spirit.

After staying there sporadically, Descartes settled permanently in Holland in the spring of 1629. It was in these Batavian lands that the philosopher published his most famous texts: Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), Principles of Philosophy (1644) and the illustrious Discourse on the Method published in Leiden in 1637.

Descartes' opposition to the scholastic tradition, his development of the philosophy of doubt, and his desire to align all knowledge with mathematical certainty, did not fail to irritate the Protestant authorities.

The first of them was Voetius (see above) who did not hesitate to launch a cabal, hatched in the shadows, against Descartes and his friend Henricus Regius, professor at the University of Utrecht.

The Utrecht controversy was launched, pitting Voetius against Descartes head-on. Voetius then instigated the publication of a polemical pamphlet , Admiranda methodus, written by his student Martin Schook, in which Descartes was described as "a lying mouth," "a bastard of Christianity."

Descartes, recognizing in these lines the targeted attacks of Voetius, wrote an open letter to the rector. Asserting that he was in no way connected with the Admiranda pamphlet, Voetius obtained the support of the city and university of Utrecht – “ a city prone to mutiny and dominated by the rebellious spirit of Voetius ” – which confirmed their 1642 condemnation prohibiting any writing relating to Descartes.

On March 23, 2005, exactly 363 years later, the Senate of the prestigious University of Utrecht—through the voices of Rector Willem Gispen and Mayor Annie Brouwer-Korff—officially ended the philosopher's exile, rehabilitating him in a solemn declaration, read in Latin (!), and abrogating the judgment upheld on March 24, 1642, which condemned "Descartes's new philosophy." It is therefore striking to note that this belated rehabilitation of Descartes perfectly mirrors that of Galileo, himself exiled in 1633 by the Catholic Inquisition and absolved in 1992 by Pope John Paul II. Both scholars—whose principles were intrinsically linked—and who were then opposed to two distinct Churches, had to wait 360 years before their work was deemed valid.

The problem of the three circles at the origin of Descartes' Theorem .

In October 1643, "in concert with Pollot, Descartes had proposed to the princess [Elisabeth, daughter of Frederick V, King of Bohemia] a problem which seemed to him the most suitable to exercise the sagacity of mathematicians, the problem of the three circles" (Charles Adam, Life and Works of Descartes, 1910, p. 411).

"The problem is so difficult that it seems to me that an angel who had received no other instruction in algebra than that given to him by St. [Stampioen?] could not solve it without a miracle," he confessed to Pollot, almost embarrassed. And yet, Princess Elisabeth solved it! Convinced, Descartes entrusted her with his own method for tangent circles, giving her the key to his algebra and revealing the two theorems he constantly used to solve problems, which, in his eyes, summarized all of geometry: the properties of right triangles and the properties of similar triangles. From 1643 onward, a rich and regular correspondence—nearly sixty letters—began between Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618–1680) and René Descartes. This epistolary relationship, initiated by the princess in the spring of 1643, offers a valuable testimony to the moral, philosophical, spiritual and mathematical principles of the great man.

The correspondence, which continued until Descartes' death in 1650, was published in 1935 by Boivin under the title * Letters on Morality*. In 1644, in homage to the unexpected mathematician who had become a privileged correspondent, Descartes dedicated his *Principia philosophiae* to Princess Elisabeth .

________________________________________________________

Origin :

Collection of the Marquis de Queux de Saint-Hilaire (the letter was first published by Victor Egger in the Annals of the Faculty of Letters of Bordeaux).

Drouot auction – December 1981.

Private collection.

Bibliography:

. Unpublished letters of Descartes. E. of Budé. Durand & Pedone-Lauriel (1868, pp. 12-16)

Annals of the Faculty of Letters of Bordeaux. Victor Egger (1881, pp. 190-191)

Adam and Tannery, Works of René Descartes, IV: Correspondence , letter no. CCCXX.

Descartes: Works/Letters , Pléiade, Gallimard, 1999, Paris, p. 1108

. Life of Mr. Descartes , Adrien Baillet, Éditions Table Ronde, Paris, 1992, II.

Descartes , Correspondence , Volume IV, J. Vrin Philosophical Bookstore.