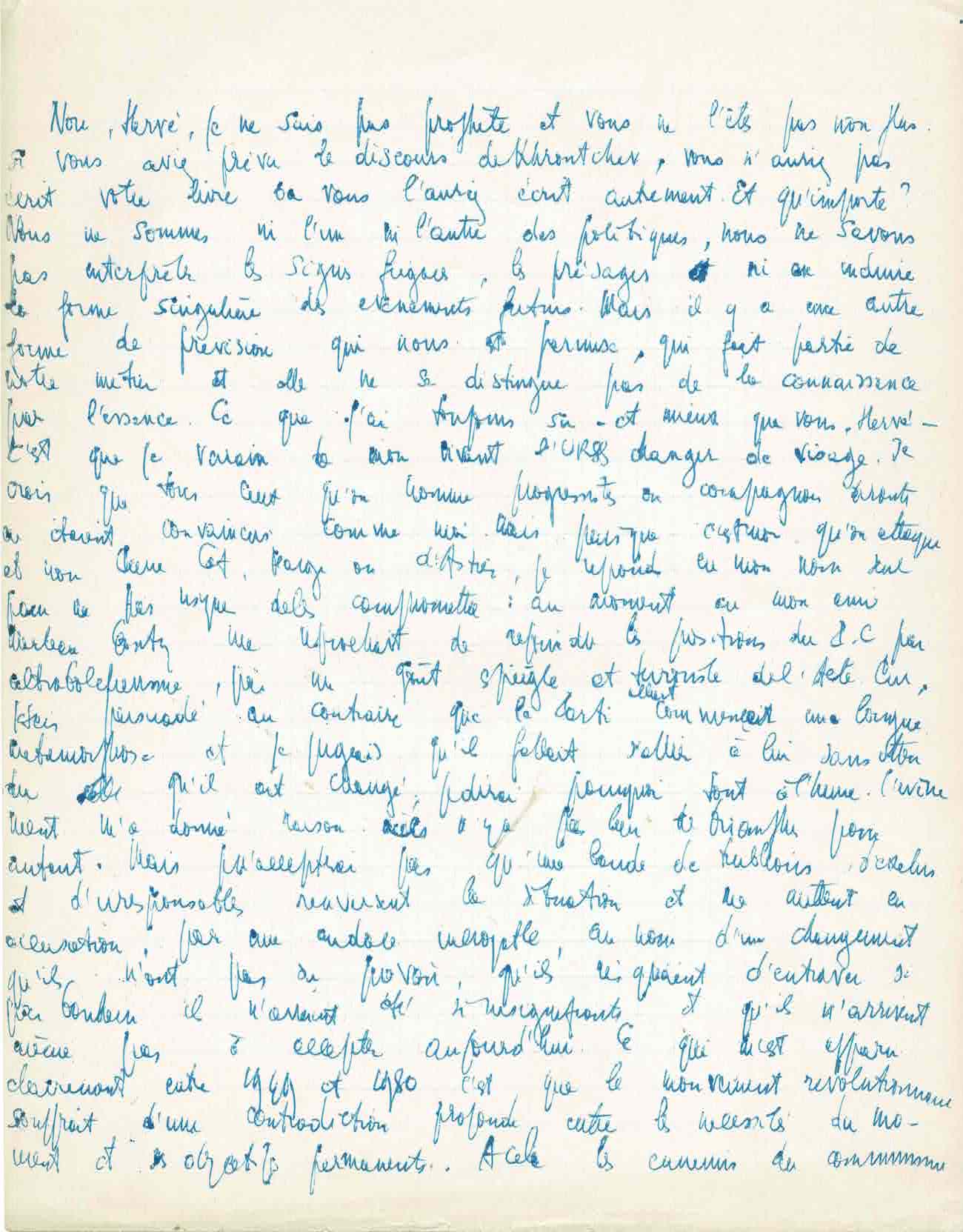

Jean paul Sartre (1905.1980)

Autograph manuscript.

Four large pages in-4° on squared paper.

Slnd. [Spring 1956]

“What became clear to me between 1949 and 1950 was that the revolutionary movement suffered from a profound contradiction between the needs of the moment and its permanent objectives. »

Dense and important political manuscript, first draft, of the French communist philosopher developing, in the form of an open letter, his arguments of contradiction following the publication of the polemical and anti-Stalinist pamphlet by Pierre Hervé, The Revolution and the Fétiches , while the resounding declarations by Nikita Khrushchev from the podium of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union – also denouncing Stalin's totalitarian excesses – created a wave of shock and destabilization throughout all communist apparatuses in the world.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

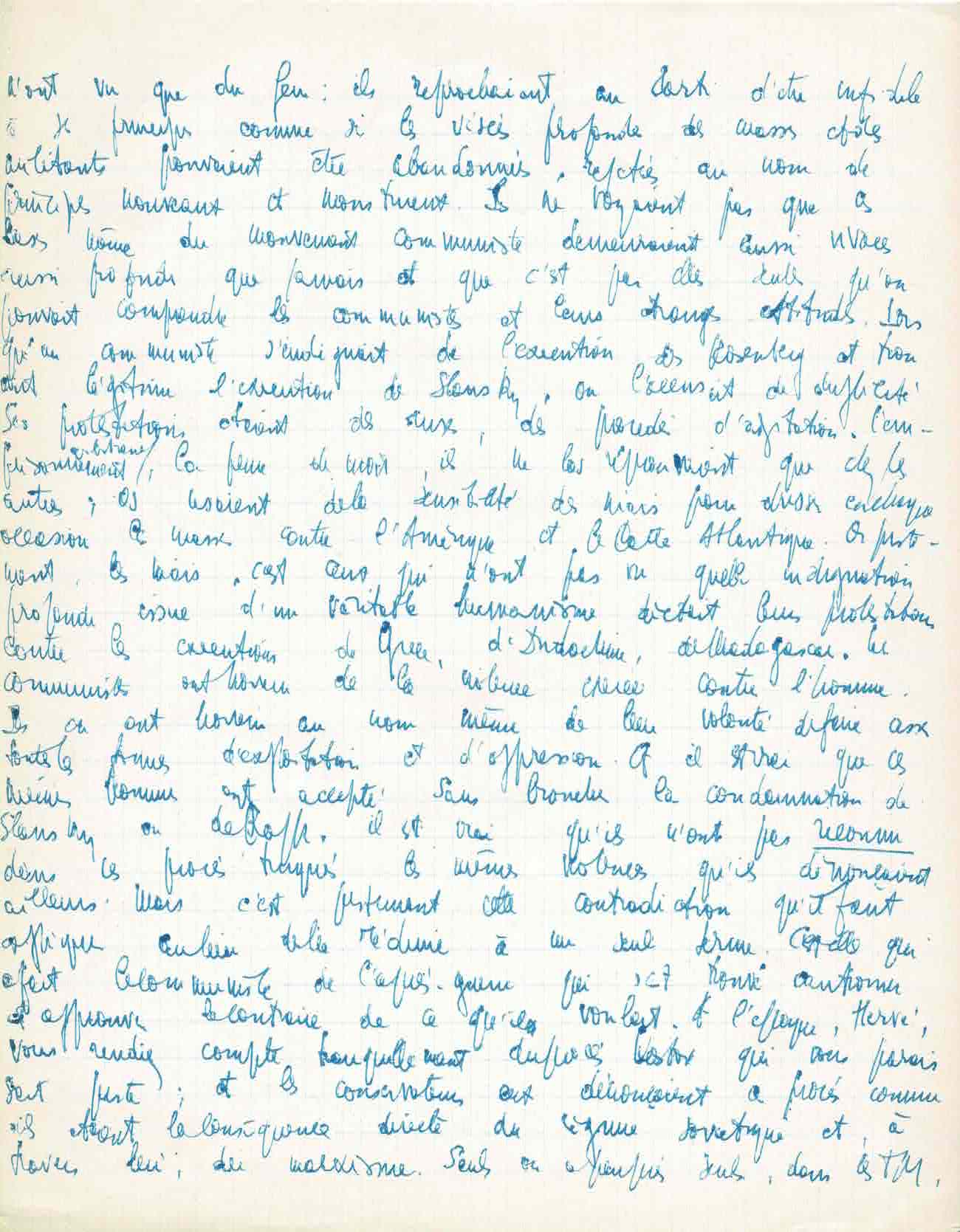

“ No, Hervé, I am not a prophet and you are not either. If you had planned Khrushchev's [sic] speech , you would not have written your book or you would have written it differently. And what does it matter? neither of us are politicians, we do not know how to interpret fleeting signs, omens, nor infer the singular form of future events. But there is another form of forecasting which is permitted to us, which is part of our profession and it is not distinguished from knowledge by essence. What I have always known – and better than you, Hervé – is that I will see the USSR change in my lifetime . I believe that all those who are called progressives or fellow travelers were convinced of this as I was. But since it is me who is being attacked and not (…) or Astier, I respond in my name alone so as not to risk compromising them: at the time when my friend Merleau Ponty criticized me for joining the positions of the PC by ultra-Bolshevism, through a mischievous and terrorist taste for the Pure Act, I was convinced on the contrary that the party was beginning a long metamorphosis and I judged that we had to ally ourselves with it without waiting for it to have changed. I'll say why later. The event proved me right, there is no reason to triumph however. But I will not accept that a group of troublemakers, excluded and irresponsible people reverse the situation and indict me, with incredible audacity, in the name of a change that they were unable to foresee, which they risked hindering if fortunately they had not been so insignificant and which they cannot even accept today.

What became clear to me between 1949 and 1950 was that the revolutionary movement suffered from a profound contradiction between the needs of the moment and its permanent objectives. The enemies of communism saw nothing but fire: they accused the party of being unfaithful to its principles as if the deep aims of the masses and the militants could be abandoned, rejected in the name of new and monstrous principles. They did not see that the very bases of the communist movement remained as alive, as deep as ever and that it was through them alone that we could understand the communists and their strange attitudes. When a communist was outraged by the execution of the Rosenbergs [Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, New York communist activists, executed in June 1953] and found the execution of Slansky [Rudolf Slansky, communist activist executed in 1952] legitimate, we accused him of duplicity. His protests were ruses, methods of agitation. Imprisonment, the death penalty, they only condemned in others. They used the sensitivity of third parties to divide the masses against America and the Atlantic boot at every opportunity. But precisely, the third parties are those who did not see what deep indignation stemming from a true humanism dictated their protests against the executions in Greece, Indochina, Madagascar. Communists hate violence against people. They hate it in the very name of their desire to put an end to all forms of exploitation and oppression. And it is true that these same men accepted without flinching the condemnation of Slansky or Rajk. It is true that they did not recognize in these rigged trials the same violence that they denounced elsewhere. But it is precisely this contradiction that must be explained instead of reducing it to a single term. It was she who created the post-war communist who found himself endorsing and approving the opposite of what he wanted.

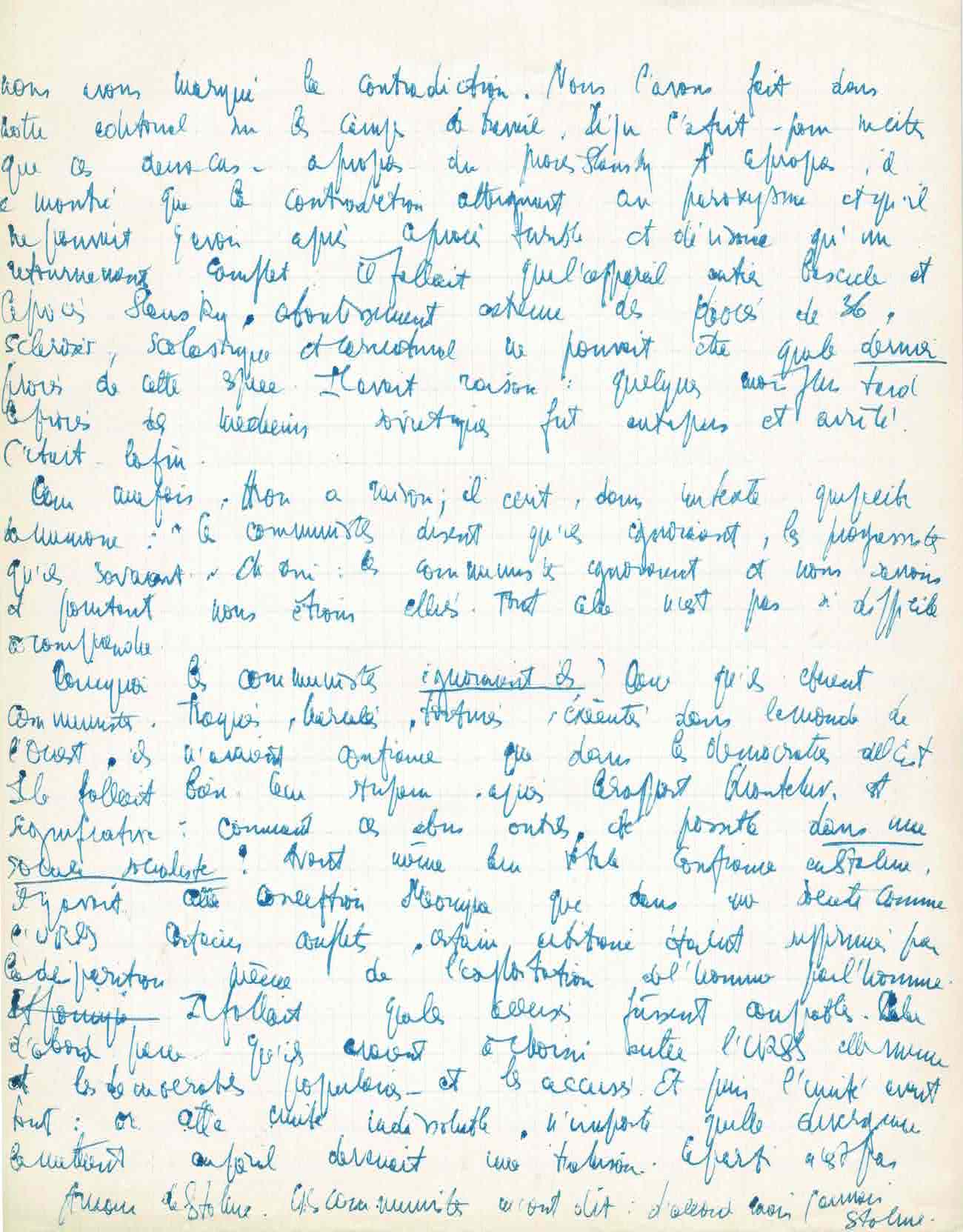

At the time, Hervé, you quietly reported on the Kostov trial [Traïcho Kostov (1897-1949), leader of the Bulgarian Communist Party, sentenced to death and executed in 1949, following a rigged trial] which seemed to you just ; and the conservatives discovered this trial as if it were the direct consequence of the Soviet regime and, through it, of Marxism. Alone or almost alone, in the TM [Modern Times], we marked the contradiction. We did this in our editorial on labor camps. Péju did it – to cite only these two cases – regarding the Slansky trial. In this regard, he showed that the contradiction reached paroxysm and that after this terrible and derisory trial there could only be a complete reversal: the entire apparatus had to topple and the Slansky trial, the external outcome of the trials of 36, sclerotic, scholastic and caricature could only be the last trial of this species. He was right: a few months later the trial of the Soviet doctors was initiated and stopped. It was the end.

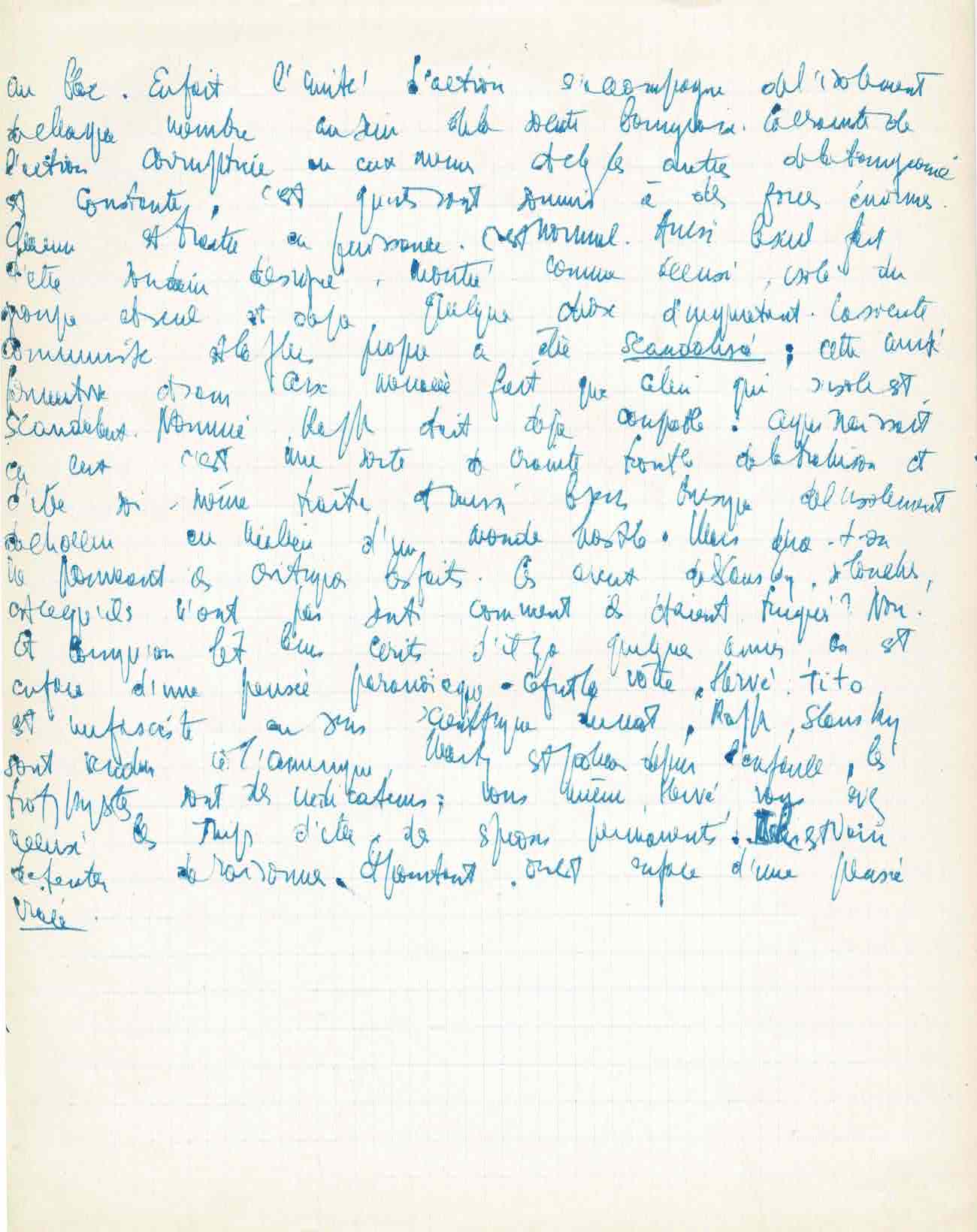

For once, Aron is right ; he writes, in a text that I quote from memory: “The communists say that they did not know, the progressives that they knew. Yes: the communists were unaware and we knew and yet we were allies. All this is not so difficult to understand. Why were the communists unaware ? Because they were communists. Hunted, harassed, tortured, executed in the Western world, they only had confidence in the democracies of the East. It was necessary. Their astonishment, after the Krutchev [sic] report, is significant: how were these abuses possible [ sic ] in a socialist society ? Even before their total confidence in Stalin, there was this [theoretical] conception that in a society like the USSR certain conflicts, certain arbitrariness were suppressed by the very disappearance of the exploitation of man by man. The accused had to be guilty. Firstly because they had to choose between the USSR itself and the popular democracies – and the accused. And then unity was everything: but this indissoluble unity, any divergence endangering it became a betrayal. The party is not Stalin's love. The communists told me: okay, but never Stalin as a whole. In fact, unity of action is accompanied by the isolation of each member within bourgeois society. The fear of corrupting action in themselves and in others of the bourgeoisie is constant. This is because they are subject to enormous forces. Everyone is a potential traitor. It's normal. Also the mere fact of suddenly being desperate, shown as accused, isolated from the group and alone is already something worrying.

Communist society is the most likely to be scandalized : this [……] and constantly threatened means that those who isolate themselves are scandalous. Named, Rajk was already guilty. What was born in them was a sort of fear [disorder] of betrayal and of being a traitor oneself and also [… …] of the isolation of […] in the middle of a hostile world. But it will be said that they could not criticize the facts. Didn't Slansky's confession, so shady, feel like it was faked? No. And when we read their writings from a few years ago, we are faced with paranoid thinking. It was yours, Hervé. Tito is a fascist in the scientific sense of the word. Rajk, Slansky are sold to America. Marty is […] since childhood, Trotskyists have been informers; you yourself, Hervé, have accused the Jews of being permanent spies. It is futile to try to reason. And yet we are faced with a true .”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Former resistance fighter and professor of philosophy, Pierre Hervé (1913.1993) was elected communist deputy for Finistère in October 1945. Re-elected during the legislative elections of November 1946, he led in parallel (!) a career as a journalist at Libération, then at L'Humanité of which he becomes the deputy director. Abandoning his political mandate in June 1948, he devoted himself to Weekly Action .

At the dawn of 1956, Hervé published " The Revolution and the Fétiches " condemning the dogmatism of the Communist Party, inviting the organization to free itself from "a fetishistic scholasticism to return to its authentic spirit and open itself to the immense aspiration of men . The PCF's response was almost instantaneous and it was excluded just before the opening of the 20th party congress.

As a result, several articles and open letters from Pierre Naville, Pierre Hervé and Jean-Paul Sartre were published; the latter insulting each other for several months in an obscure political contest in the light of the post-Stalinist Soviet situation.

Hervé will finally respond to the various criticisms of which his work had been the subject in Letter to Sartre and to a few others at the same time (La Table Ronde, May 1956).