Edmond JALOUX (1878.1949)

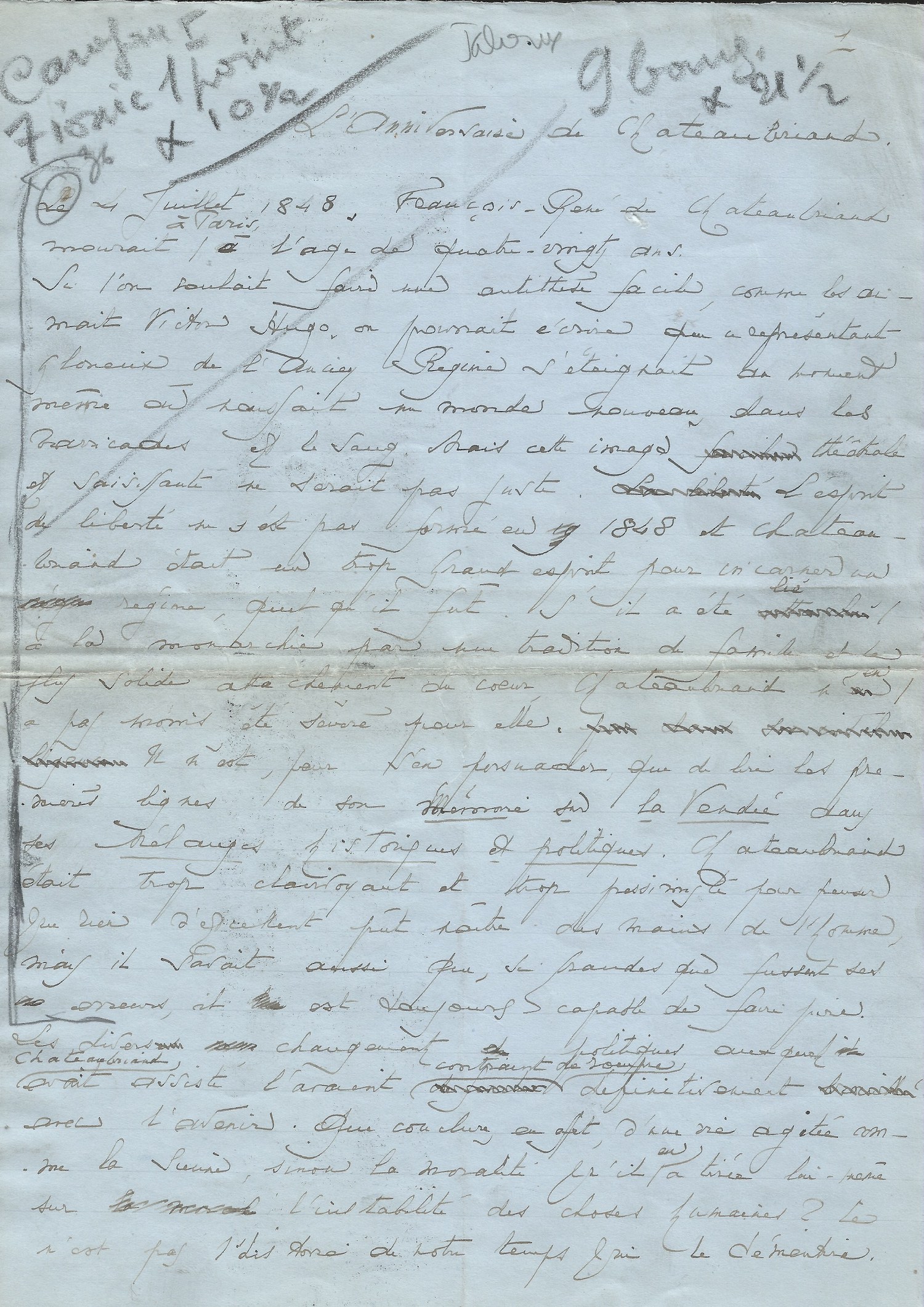

Signed autograph manuscript – Chateaubriand’s birthday.

Four folio pages on blue paper. Slnd.

Manuscript in first draft with typographer's annotations in the margin.

“The great French prose is that of Rabelais, Montaigne, Bossuet, Châteaubriant and Victor Hugo. »

The Academician pays tribute to Chateaubriand, master of our national literature.

___________________________________

On July 4, 1848, François-René de Chateaubriand died in Paris at the age of eighty. If we wanted to make an easy antithesis, as Victor Hugo liked them, we could write that this glorious representative of the old regime died out at the very moment when a new world was born amid barricades and blood. But this dramatic and striking image would not be fair. The spirit of freedom was not formed in 1848 and Chateaubriand was too great a spirit to embody a regime , whatever it was. If he was linked to the monarchy by a family tradition and the strongest attachment of the heart, Châteaubriant was nonetheless severe for her. To be convinced of this, one only has to read the first lines of his Memoir on the Vendée in his Mixtures historique et politiques . Chateaubriand was too far-sighted and too pessimistic to think that anything excellent could come from the hands of man, but he also knew that, however great his errors were, he is always capable of doing worse. The various policy changes that Chateaubriand had witnessed had forced him to make a definitive break with the future. What can we conclude, in fact, from a troubled life like his, if not the morality that he himself drew from it on the instability of human things? The history of our time will not deny this.

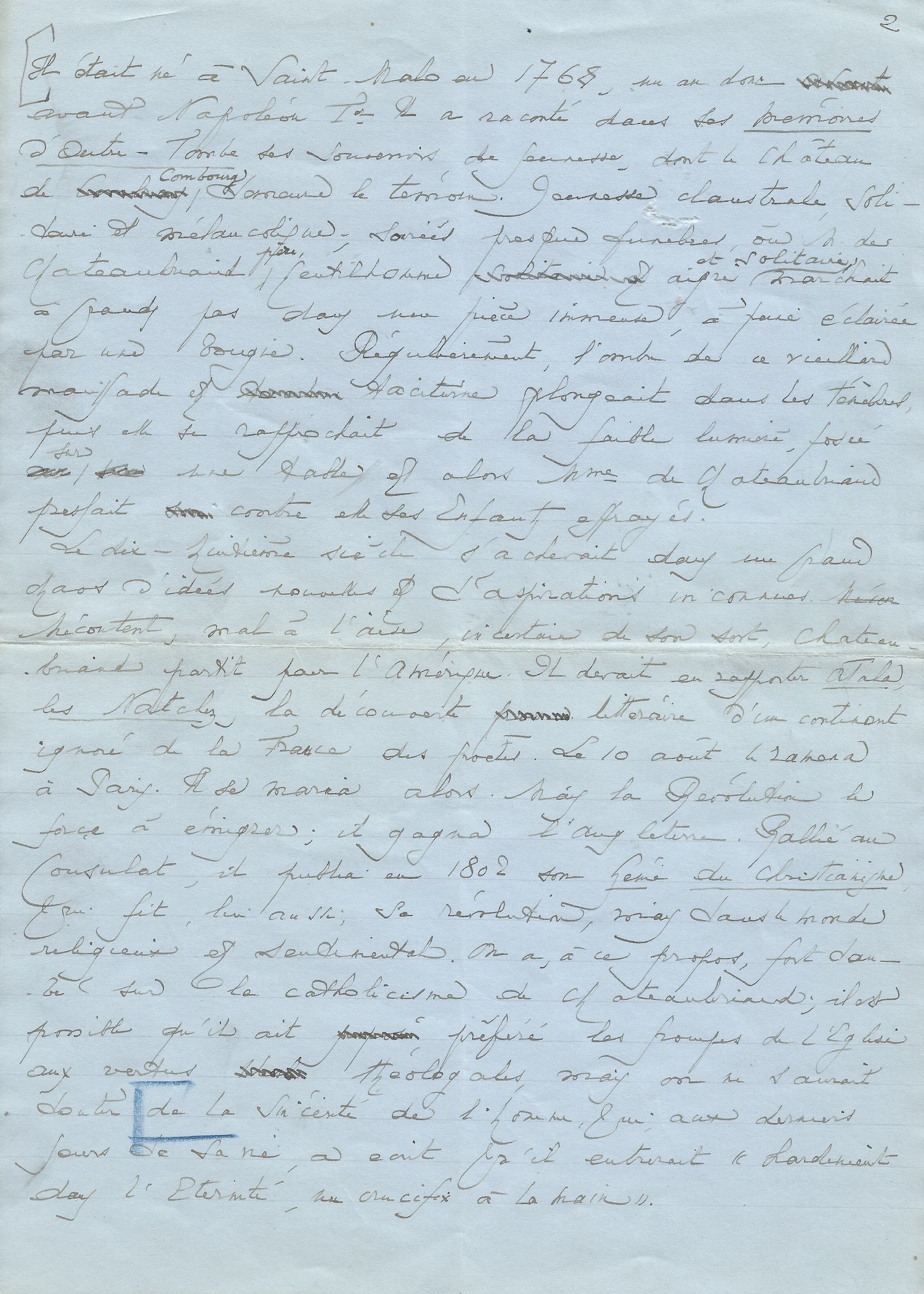

He was born in Saint-Malo in 1768, a year before Napoleon I. He recounted his youthful memories Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe , of which the Château de Combourg remains a witness. Cloistered, solitary and melancholy youth; almost funeral evenings, where M. de Chateaubriand senior, an embittered and solitary gentleman, strode through an immense room, barely lit by a candle. Regularly, the shadow of this sullen and taciturn old man plunged into the darkness then it approached the weak light, placed on a table and then Madame de Chateaubriand cursed her frightened children against it.

The eighteenth century ended in a great chaos of new ideas and unknown aspirations. Dissatisfied, uncomfortable, uncertain of his fate, Chateaubriand left for America. He was to bring back “ Atala, the Natchez ”, the literary discovery of a continent unknown to the France of poets. August 10 brought him back to Paris. He then married. But the revolution forced him to emigrate; he reached England. Joining the Consulate, he published in 1802 his Genius of Christianity, which also made its revolution but in the religious and sentimental world. In this regard, there was great doubt about Chateaubriand's Catholicism ; it is possible that he preferred church groups to theological virtues, but one cannot doubt the sincerity of the man, who in the last days of his life wrote that he would enter "boldly into the Eternity with a crucifix in hand.”

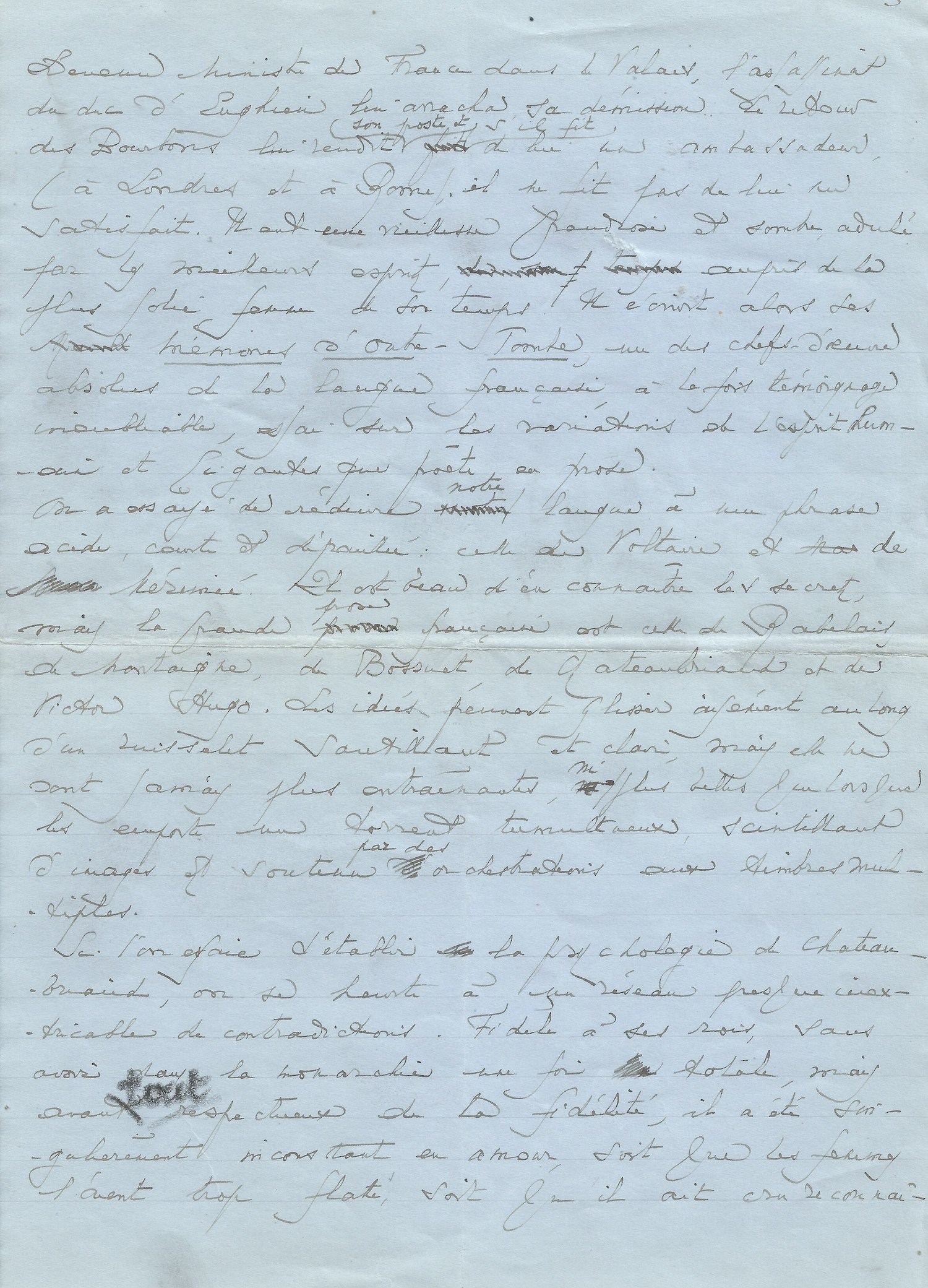

Having become Minister of France in Valais, the assassination of the Duke of Enghien forced his resignation. The return of the Bourbons restored his post and although he made him his ambassador (in London and Rome), it did not make him satisfied. He had a grandiose and dark old age, adored by the best minds, alongside the most beautiful woman of his time. He then wrote his Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe , one of the absolute masterpieces of the French language , both an unforgettable testimony and an essay on the variations of the human spirit (…)

We tried to reduce our language to an acidic, short and spare sentence: that of Voltaire and Mérimée. It is wonderful to know its secrets, but the great French prose is that of Rabelais, Montaigne, Bossuet, Châteaubriant and Victor Hugo. Ideas can slide easily along a hopping, clear rivulet, but they are never more catchy, nor more beautiful than when they are carried away in a tumultuous torrent sparkling with images and supported by orchestrations with multiple timbres.

If we try to establish Chateaubriand's psychology, we come up against an almost inextricable network of contradictions. Faithful to his kings, without having total faith in the monarchy, but above all, respectful of fidelity, he was singularly inconstant in love, whether because women flattered him too much, or because he believed he recognized in too many of different faces, the sylph that he pursued, in his adolescence, under the oaks of Combourg. Royally selfish, he was always generous, delicate towards others and charitable. Proud, he spent his life contemplating his own nothingness and suffering from it. Distracted everywhere, he was bored with everything. More dreamer than any other writer, he was first and foremost a man of action. There was something in him to make extremely diverse individuals; he was them all, in turn, and successfully.

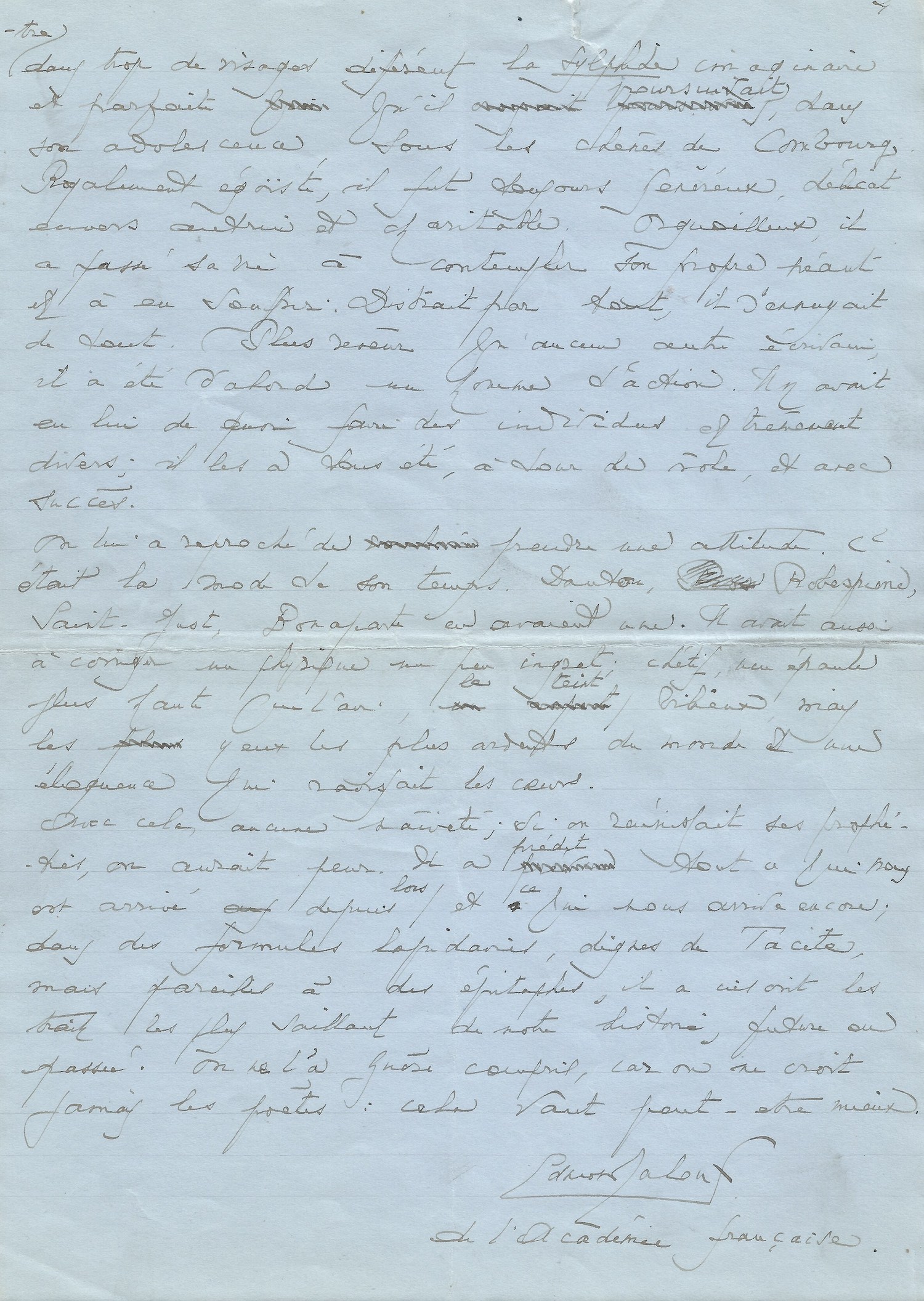

He was criticized for having an attitude. It was the fashion of his time. Danton, Robespierre, Saint-Just, Bonaparte had one. He also had to correct a somewhat unattractive physique; puny, one shoulder higher than the other, (…) but the most ardent eyes in the world and an eloquence that delighted hearts. With this, there is no naivety; if we put together his prophecies, we would be afraid. He predicted everything that has happened to us since then, and what is still happening to us; in lapidary formulas, worthy of Tacitus, but like epitaphs, he inscribed the most salient features of our history, future or past. We hardly understood it, because we never believe poets : that is perhaps better.

Edmond Jaloux of the French Academy.