Benjamin CONSTANT (1767.1830)

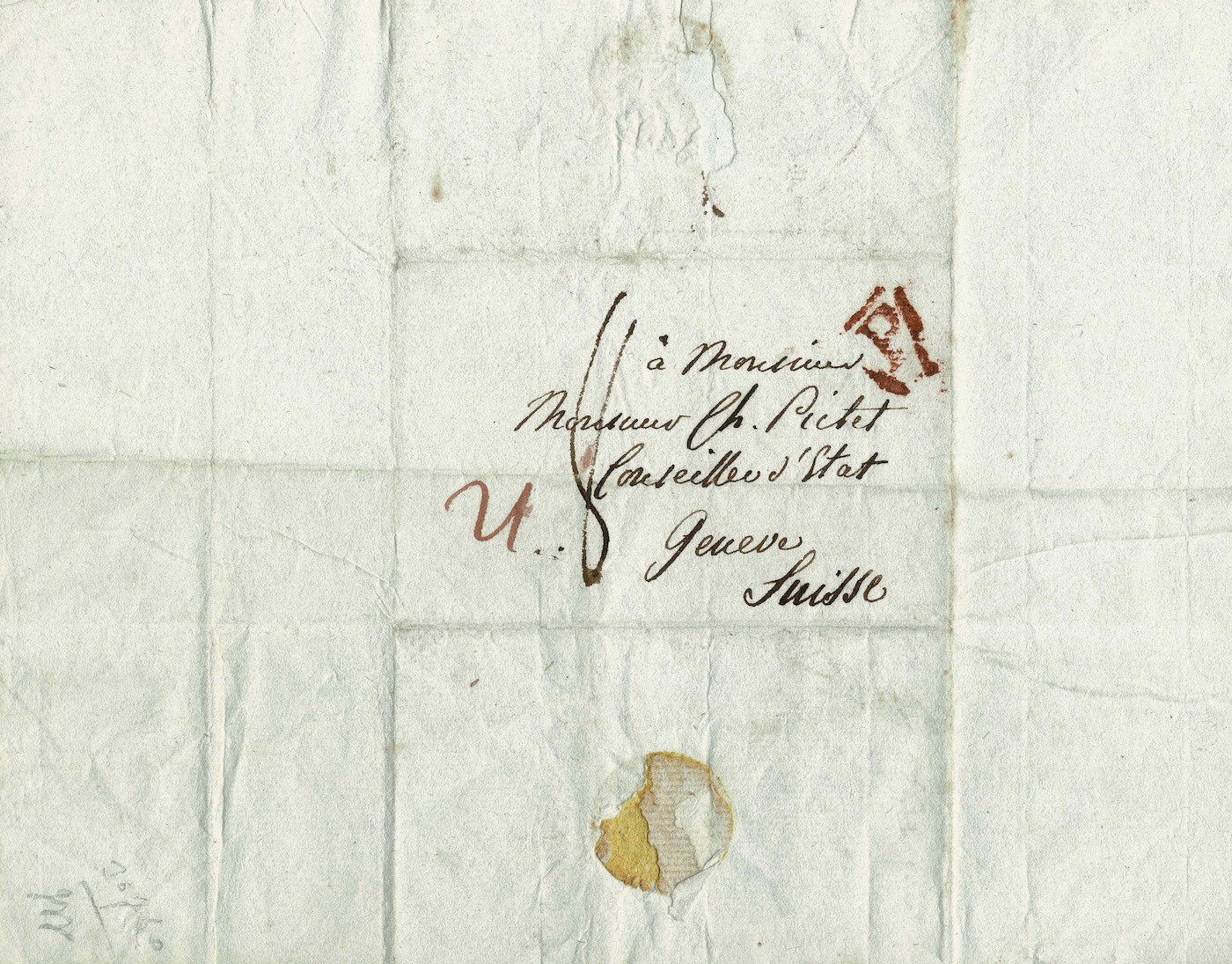

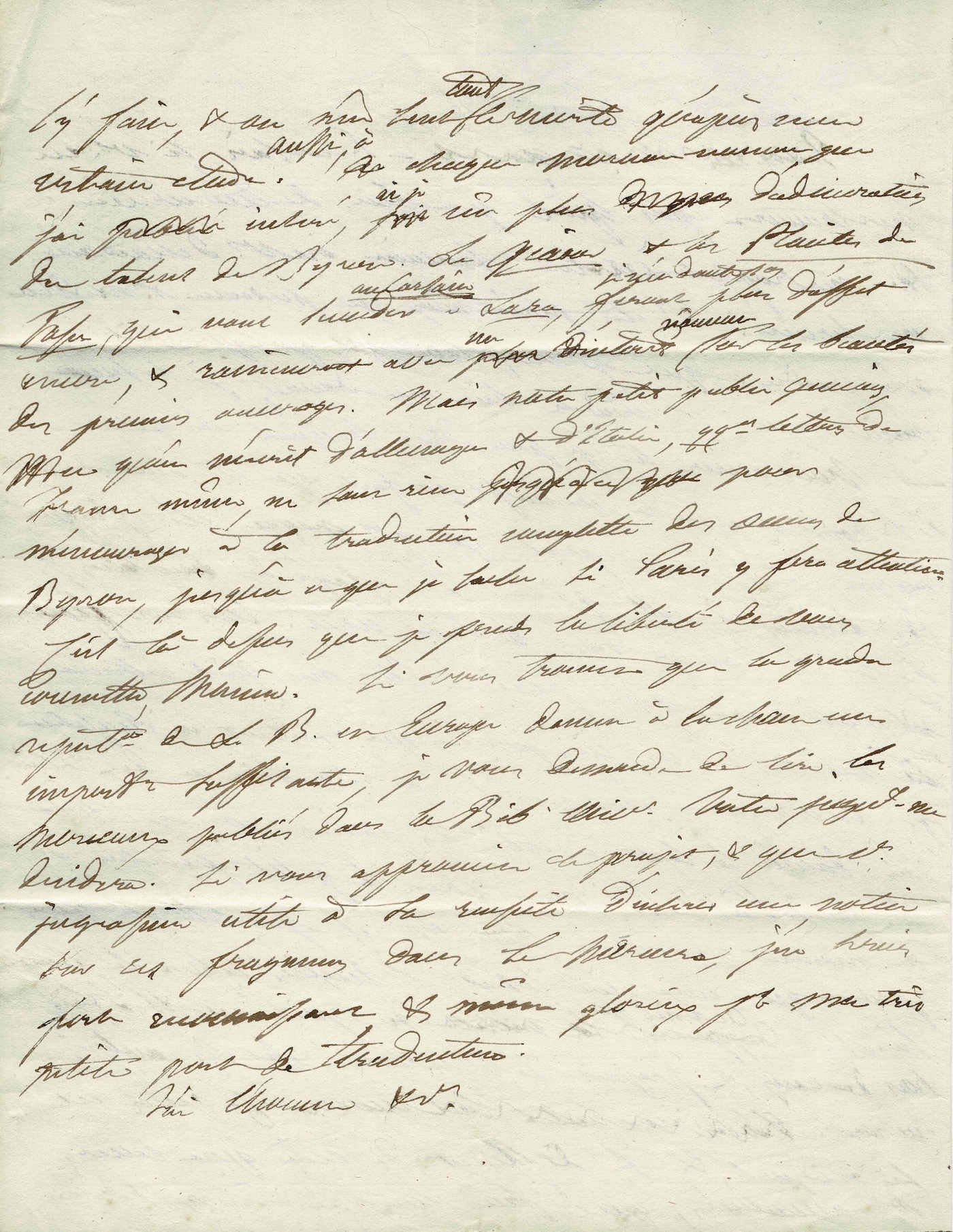

Autograph letter signed to Charles Pictet de Rochemont.

Two pages in quarto. Autograph address.

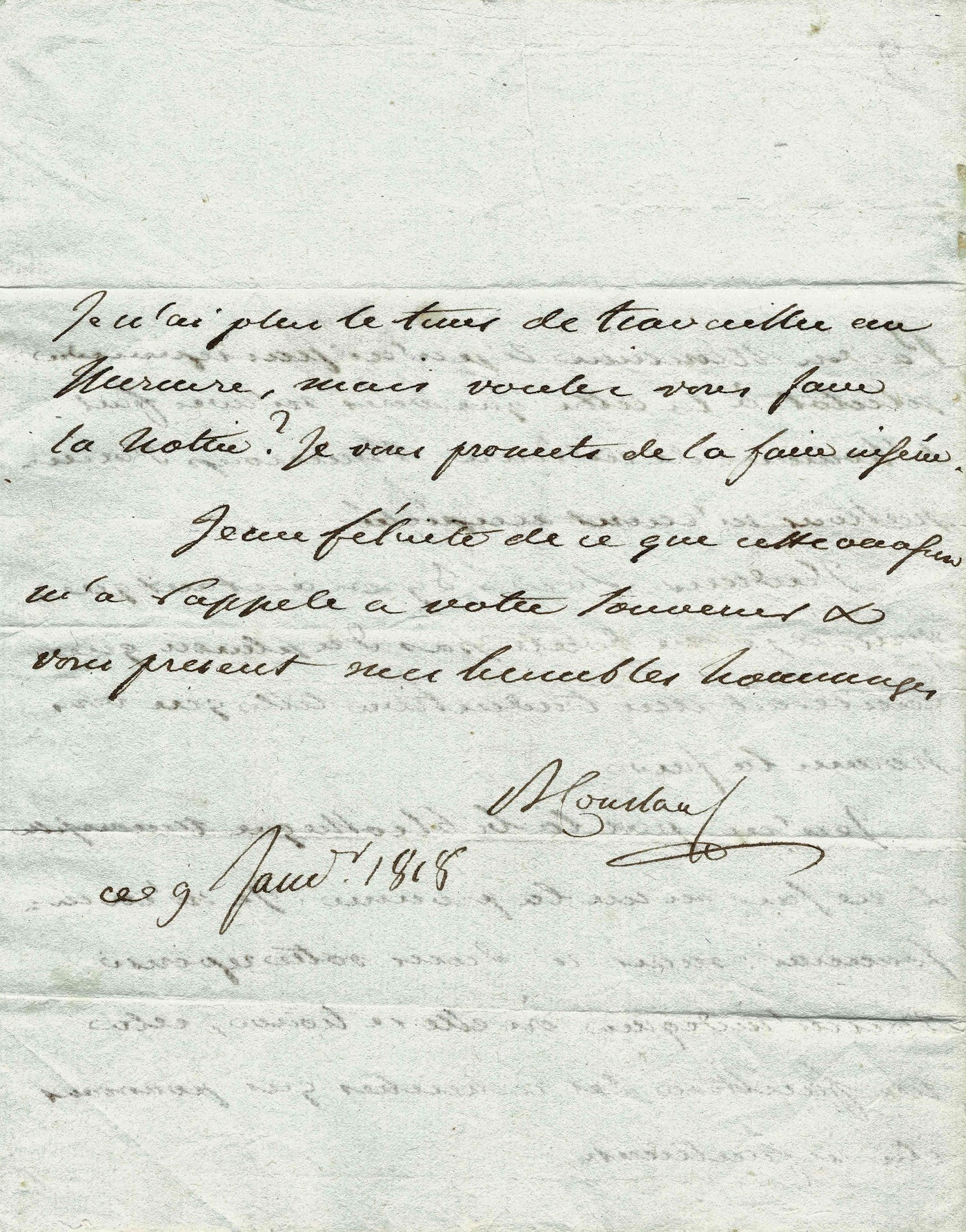

No place. January 9, 1818.

"I admire Lord Byron as much as you do.". »

Prompted by a long letter from Charles Pictet (of which we include the autograph draft), Benjamin Constant testifies to his admiration for Lord Byron and enthusiastically receives the project to translate the works of the British poet.

________________________________________________________

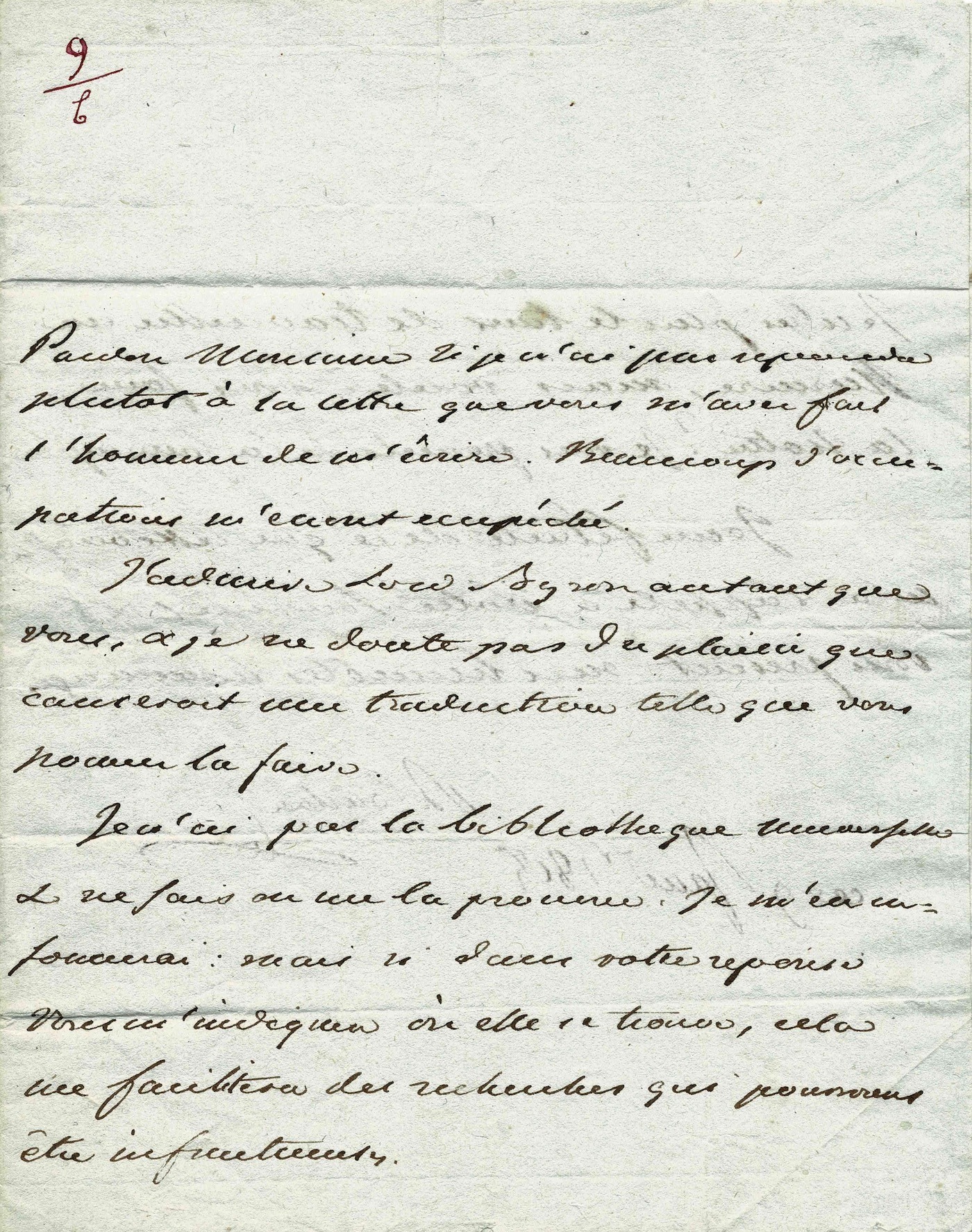

“Please excuse me, sir, for not replying sooner to the letter you honored me with. Many commitments have prevented me. I admire Lord Byron as much as you do , and I have no doubt of the pleasure a translation such as yours would bring. I do not have access to the Bibliothèque Universelle and do not know where to obtain it. I will inquire about it; but if in your reply you indicate where it is located, it will facilitate research that might otherwise prove fruitless. I no longer have time to work on the Mercure , but would you be willing to write the notice? I promise to have it published. I am delighted that this occasion has reminded me of you and offer you my humble regards. B. Constant.”

________________________________________________________

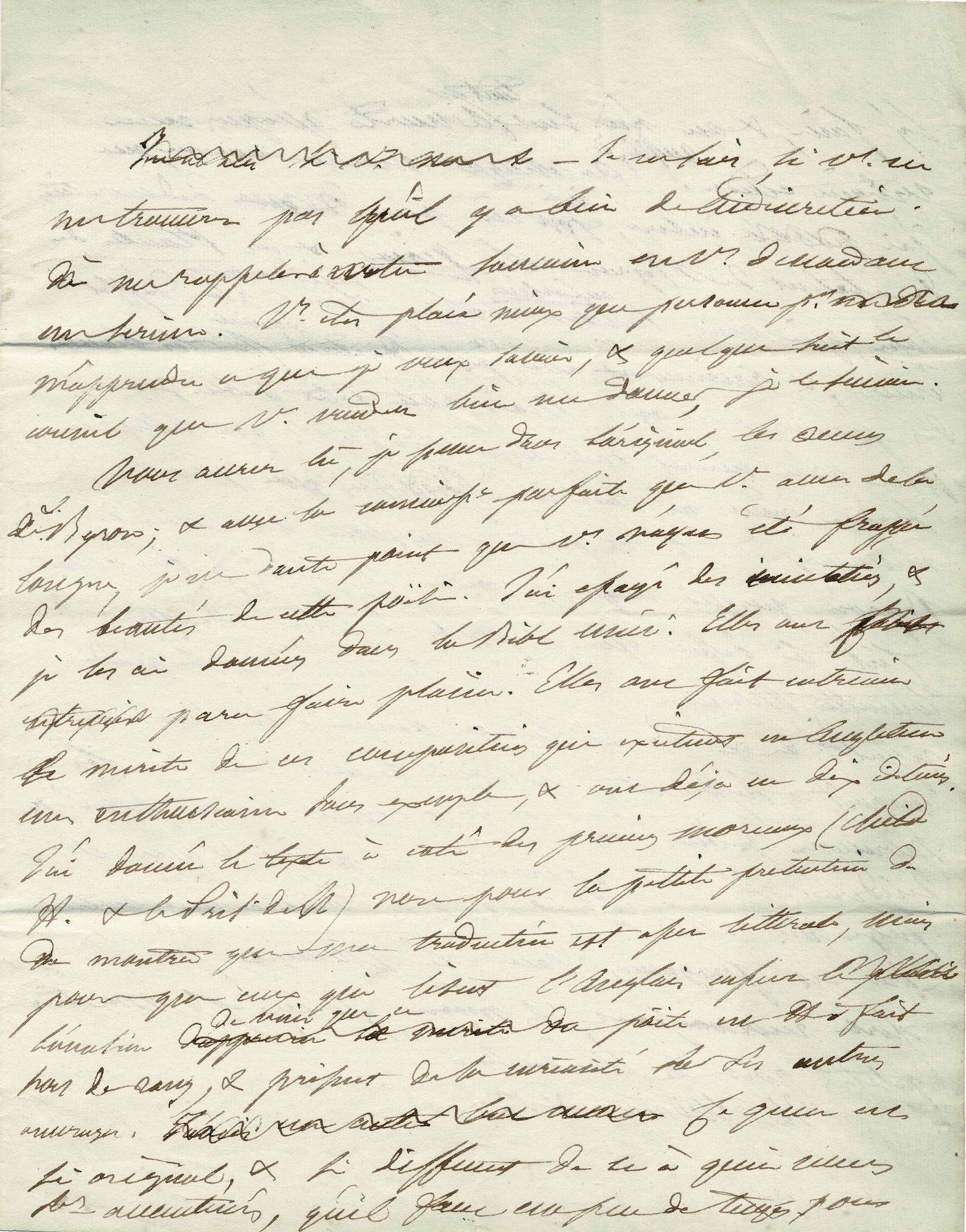

We enclose the original manuscript of Charles Pictet de Rochemont's letter to Benjamin Constant (two pages, large quarto) dated December 20, 1817: “Sir, I don't know if you won't indiscreet to remind you of my existence by asking you for a favor. You are in the best position to tell me what I want to know, and whatever advice you may give me, I will follow it. You have read, I believe in the original, the works of Lord Byron; and with your perfect knowledge of the language, I have no doubt that you were struck by the beauties of this poetry . I have tried some imitations, and I published them in the Bibliothèque Universelle . They seemed to be well received. They revealed the merit of these compositions, which are generating unprecedented enthusiasm in England, and have already gone through ten editions.” I have included the text alongside the first pieces (Childe Harold and The Prisoner of Chillon ) not out of any petty pretension to show that my translation is literal enough, but so that those who read English might have the opportunity to see that this poet is quite exceptional and become curious about his other works. This genre is so original, and so different from what we are accustomed to, that it takes some time to get used to it, and one only fully appreciates its merit after a thorough study of each new piece I have inserted. Have I ever had more admiration for Byron's talent? The Giaour and the Complaints of Tasso, which will follow The Corsair and Lara, will, I have no doubt, have an even greater impact and will draw readers back with renewed interest to the beauties of the earlier works. But our small Genevan readership, while I receive letters from Germany and Italy, and even a few from France, does nothing to encourage me to undertake a complete translation of Byron's works, until I know whether Paris will take notice. It is on this point that I take the liberty of submitting it to you, Sir. If you find that Lord Byron 's in Europe lends sufficient importance to the matter, I ask you to read the excerpts published in the Bibliothèque Universelle . Your judgment will decide. If you approve this project, and if you deem it useful for its success to include a notice on these fragments in the Mercure, I would be most grateful and even proud for my very small contribution as a translator. I have the honor… »

________________________________________________________

In 1816, while writing a note on translations from Italian, Charles Pictet de Rochemont (1755-1824) remarked in the Bibliothèque universelle, the Geneva journal of which he was one of the founders, that it would be desirable to see French translations of Lord Byron and Walter Scott published, "who, in different genres, currently uphold the glory of English Parnassus." This note already set the tone, and, because one is never better served than by oneself, Pictet undertook the following year, and then in 1818 and 1819, to publish his translations. He began with extracts from the third canto of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, The Prisoner of Chillon, The Corsair, Lara , and The Giaour. Then, in the next volume, he included Tasso's Laments, The Siege of Corinth, and extracts from the fourth canto of Childe Harold, and so on

Choix de poésies de Byron, Walter Scott et Moore" appeared at the Geneva publisher JJ Paschoud. The title page announces a "free translation by one of the editors of the Bibliothèque universelle" – that is to say, by Charles Pictet.

Lord Byron's Works from 1819 onwards (ten volumes published up to 1821), a text that would be corrected and augmented several times in the following years, Charles Pictet's translation exerted an influence that Lamartine himself attested to. His friend Louis de Vignet, passing through Geneva, acquired the volumes of the Bibliothèque universelle from the bookseller Paschoud and sent them to him. "A book," Lamartine would later write, "is an event in the life of the soul: it is sometimes a revolution… Lord Byron's poems found me in one of those pre-existing states that prepare the poet for the silent audience of all the senses and all the imagination. That was in 1818; I was listening to the silence of the century, and I heard no voice that resonated with my own heart, when suddenly this one vibrated in the slumbering air.

Most importantly, in a letter to Murray dated October 12, 1820, Byron himself judged Pichot and Salle's hasty translation "far inferior" to that of Charles Pictet. Reporting Moore's remark that "the French had caught the contagion of Byronism to the highest pitch," he added: "The Paris translation is also very inferior to the Geneva one, which is very fair, though in prose as well."

The meeting of the Genevan scholar and the French writer and political theorist around the high literary figure of Lord Byron, then alive, is moving: it marks a date in the history of Romanticism.