André Breton (1896.1966)

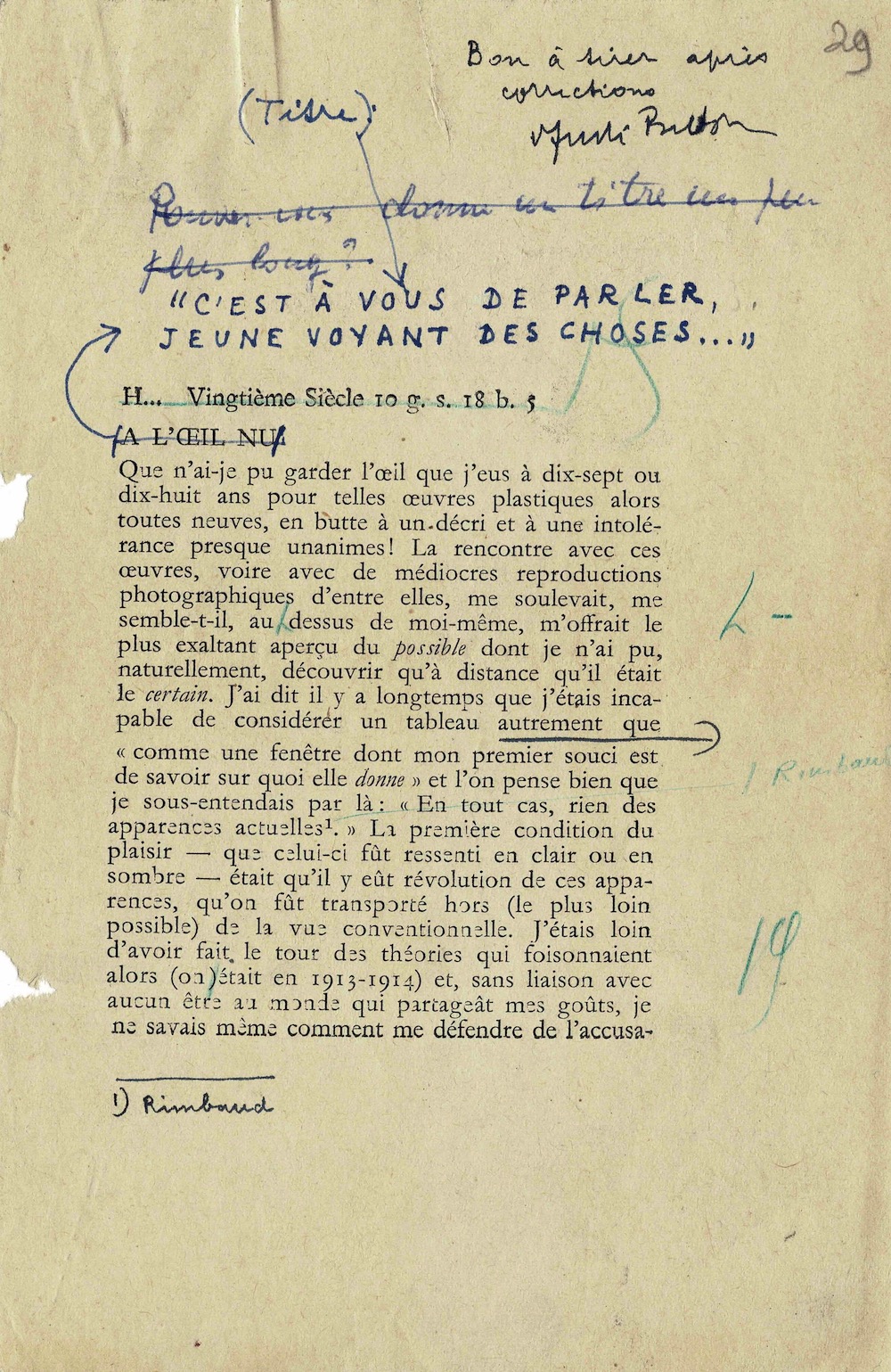

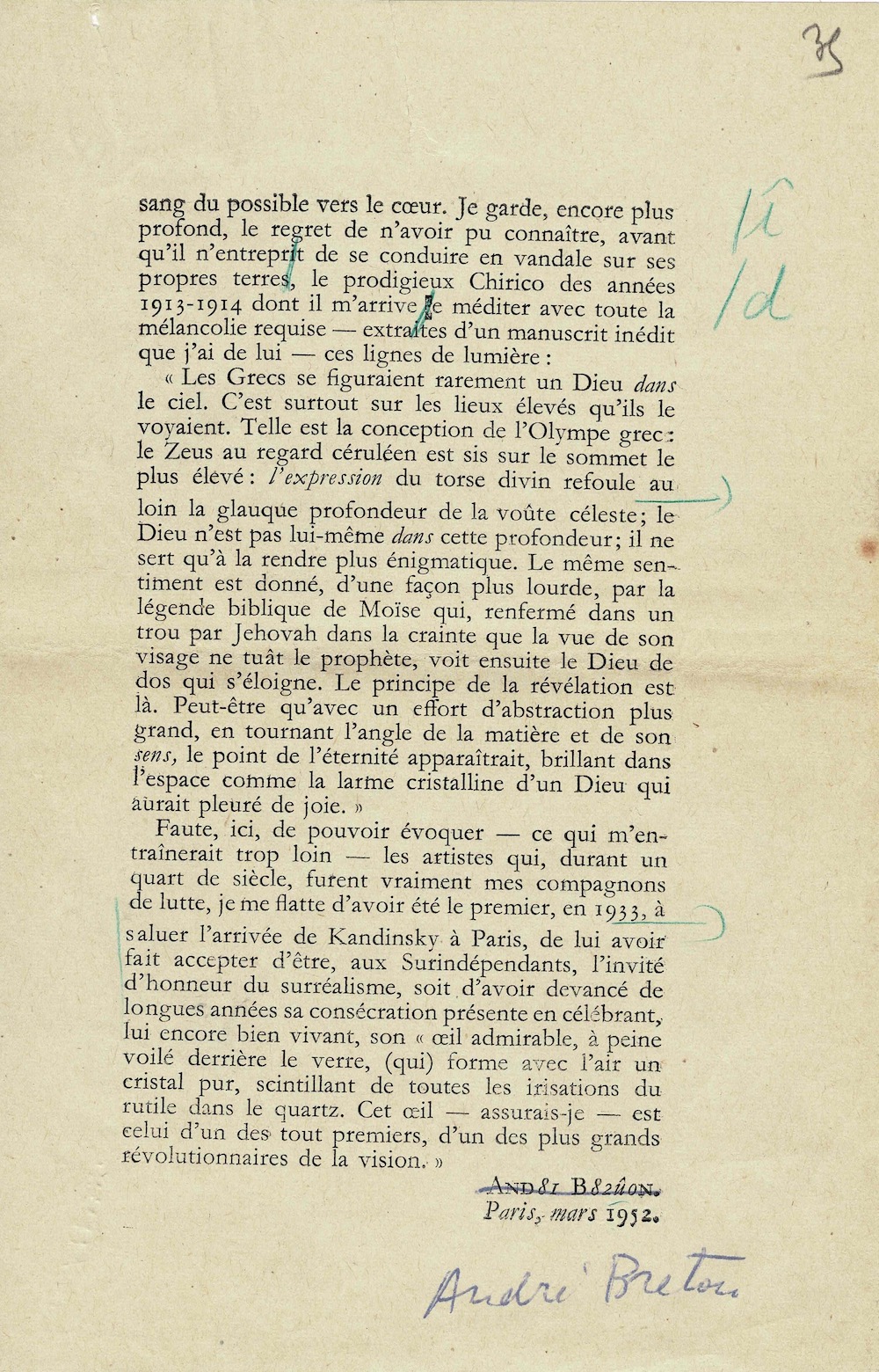

Autograph manuscript signed – TO THE NAKED EYE

Six quarto pages on cream paper.

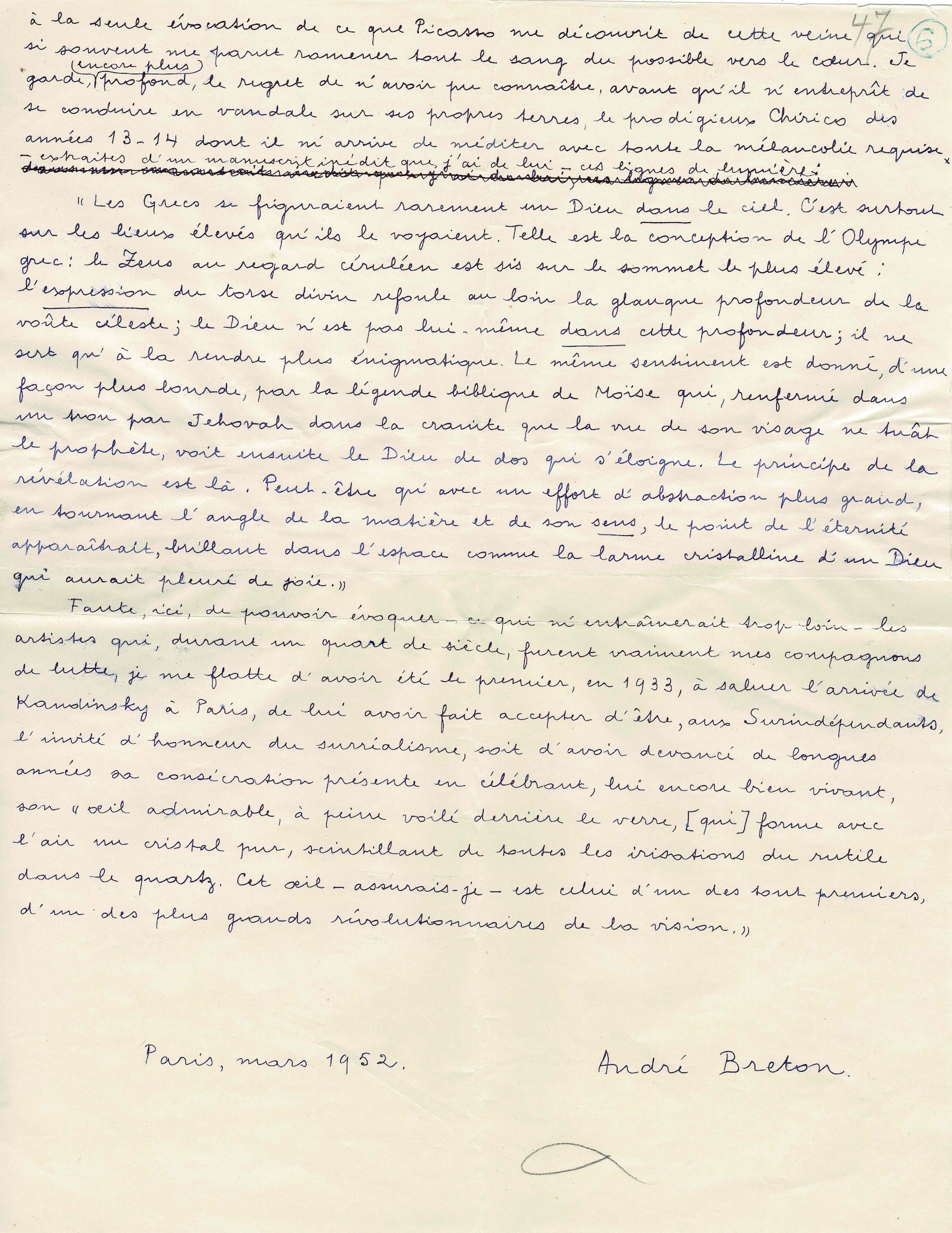

Paris. March 1952.

"I often think that this open-mindedness of youth remains the only good one."

André Breton analyzes the relationship between men and the beauty of pictorial works. Invoking the modern gaze of youth, he revisits his first artistic loves, some masterpieces from his collection and, from Picabia to Picasso, from Braque to Modigliani, the great masters who influenced and guided him in the quest for Beauty.

This text was published under the title "It is up to you to speak, young seer of things", in the magazine XXe siècle, June 1952. We are enclosing the seven pages of proofs corrected and signed by Breton.

__________________________________________________________________

TO THE NAKED EYE

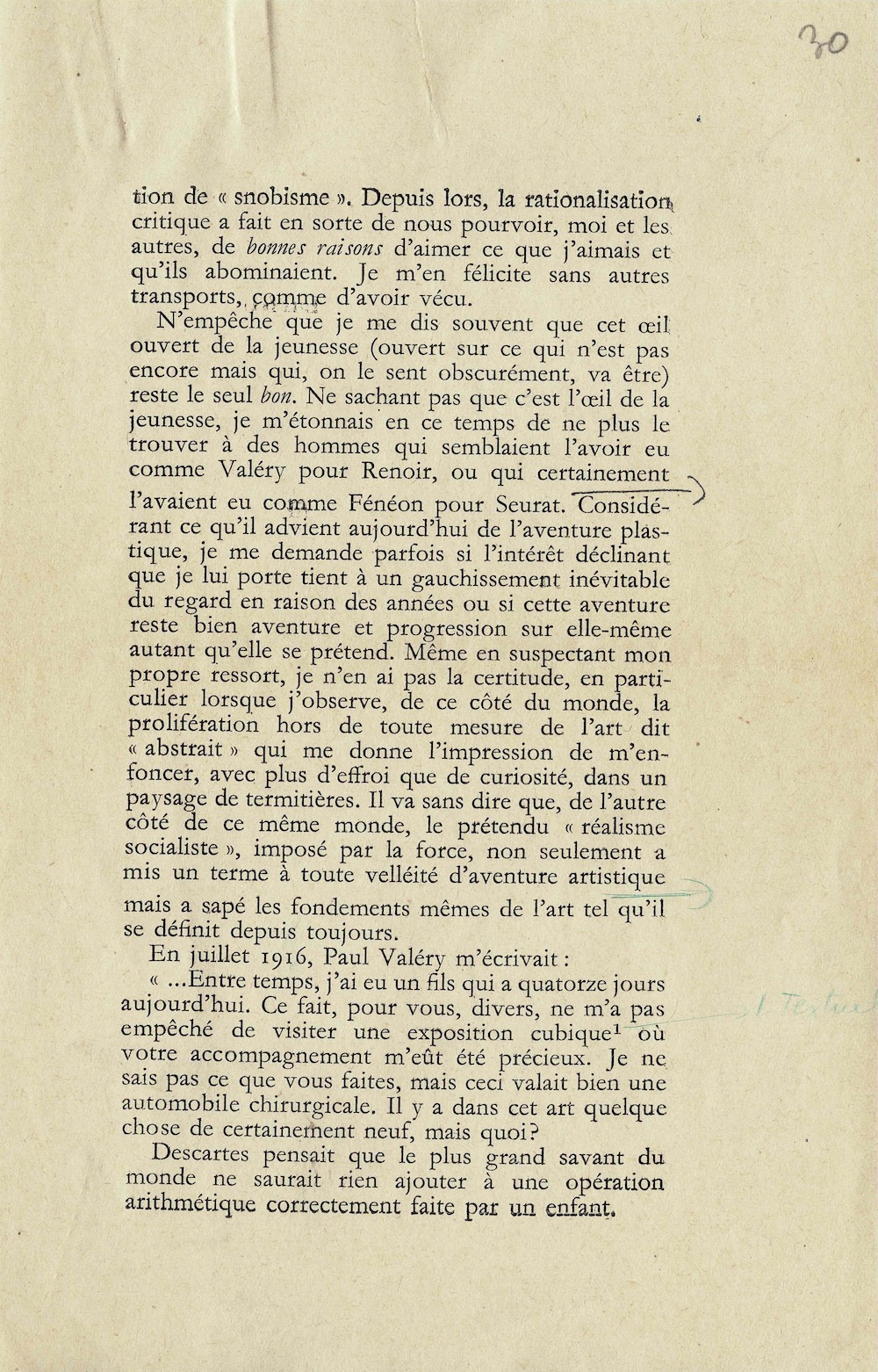

“If only I had kept the eye I had at seventeen or eighteen for such works of art, then brand new, subject to almost unanimous decriement and intolerance! The encounter with these works, even with mediocre photographic reproductions of them, lifted me, it seems to me, above myself, offered me the most exhilarating glimpse of the possible certainty of which I could only, naturally, discover from a distance . I said long ago that I was incapable of considering a painting other than ‘as a window whose first concern is to know what it looks ,’ and one can well imagine that I meant by this: ‘In any case, nothing of current appearances.’ [ * Rimbaud].” The first condition of pleasure—whether felt in light or in darkness—was that there be a revolution of these appearances, that one be transported out (as far as possible) of conventional life. I was far from having exhausted the theories that were then proliferating (it was 1913-1914), and, without any connection to anyone in the world who shared my tastes, I didn't even know how to defend myself against the accusation of "snobbery." Since then, critical rationalization has provided me and others with good reasons to love what I loved and what they abhorred. I rejoice in this without any other enthusiasm, as I do in having lived.

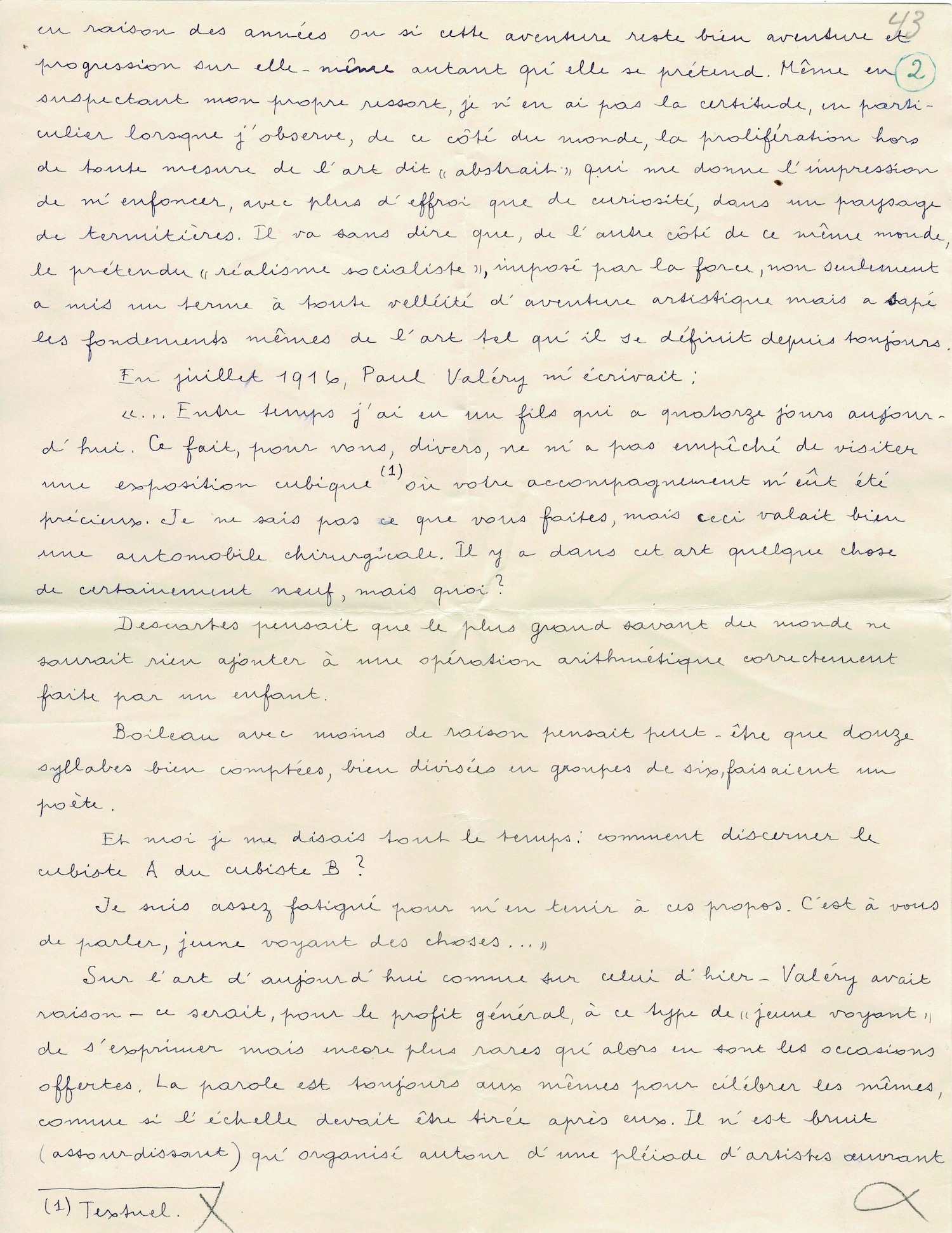

Nevertheless, I often think that this open eye of youth (open to what is not yet but which, one dimly senses, will be) remains the only true one . Not knowing that it was the eye of youth, I was surprised at the time not to find it in men who seemed to have possessed it, like Valéry for Renoir, or who certainly had possessed it, like Fénéon for Seurat. Considering what is happening today to the artistic adventure, I sometimes wonder if the declining interest I have in it stems from an inevitable distortion of perspective due to the passing years, or if this adventure remains truly an adventure and a progression within itself, as much as it claims to be. Even suspecting my own motivations, I'm not certain, especially when I observe, on this side of the world, the unchecked proliferation of so-called "abstract" art, which gives me the impression of sinking, with more dread than curiosity, into a landscape of termite mounds. It goes without saying that, on the other side of this same world, the so-called "socialist realism," imposed by force, has not only put an end to any inclination towards artistic exploration but has undermined the very foundations of art as it has always been defined.

In July 1916, Paul Valéry wrote to me: “…In the meantime, I had a son who is fourteen days old today. This fact, for you, various people, did not prevent me from visiting a Cubist exhibition where your company would have been invaluable. I don't know what you do, but this was well worth a surgical automobile. There is certainly something new in this art, but what? Descartes thought that the greatest scientist in the world could add nothing to an arithmetic operation correctly performed by a child. Boileau, perhaps less logically, thought that twelve syllables, well counted and well divided into groups of six, made a poet. And I kept asking myself: how to distinguish Cubist A from Cubist B? I am tired enough to leave it at that. It is up to you to speak, young seer of things…”

Regarding the art of today as well as that of yesterday—Valéry was right—it would be beneficial for everyone to allow this type of "young visionary" to speak, but opportunities for such expression are even rarer than they were then. The floor is always given to the same people to celebrate the same people, as if the ladder were to be pulled up after them. There is no (deafening) noise except that which is organized around a constellation of artists who have been working for half a century and from whom it would obviously be too much to ask to generate throughout their lives the interest and emotion that, in times long past, were attached to the most audacious and sublime formulation of their message. At least from my perspective, the attitude toward art should continue to be a quest in all directions and not consist of scrutinizing the slightest gestures of those who were once conquerors, when the winds of conquest no longer carry them : their contribution would still be quite significant even without that. In our time, it is unfortunate that routine and commercial speculation dictate otherwise. What sufficiently independent magazine will decide to launch an inquiry among the most receptive circles of young people to learn from them the names of the living artists who truly hold their favor and even—for there would be no fear, in this area, of extreme subjectivity in judgment—which five to ten contemporary visual artworks exert the greatest attraction on each of those consulted? I have no doubt that such an inquiry would yield surprises, that it would bring to light and promote to their rightful place the artists and works that represent not yesterday but tomorrow .

Nevertheless, if I had had to answer that question myself back when, having just discovered and begun to explore contemporary painting, it was the subject of a thrilling inquiry for me, I would have hardly hesitated in my choice. I would add that, subsequently, I was able to observe that this choice foreshadowed the recognition of a fairly wide range of values.

Some of the works that I would have pointed out then? I will name them in the order in which they appeared to me: The Portrait (of his wife) by Matisse, exhibited at the Salon d'automne of 1913, of which – although I have never seen it since – I cannot forget the crown of black feathers, the thin tawny fur and the emerald blouse (wasn't her hair café au lait?) This is for me a perfect example of the event-work (far beyond even The Joy of Living and The Dance with Capucines , which I used to go and see so often at the old Bernheim gallery on rue Richepanse, where they remained hanging for years).

Portrait of Knight X : although I have never been able to see the original—buried, like the previous one, in Moscow in the former Shchukin collection—the strange balance of the figure between a drawn curtain and the unfolded newspaper he holds in his hands intrigued and held my attention for a long time. By the same artist, on the wall of his studio around 1918, was a large Cabaret at the Front , the fate of which remains unknown to me.

The Child's Brain ," which has never left my side since the day it was displayed in the window of the Paul Guillaume gallery on rue la Boétie, so captivating that I was compelled to get off the bus to examine it at my leisure. Years after I acquired it, this painting was to return to the same spot for an exhibition: the fact that Yves Tanguy—whom I didn't yet know—passing by on a bus at the time, had the same reaction as me, is enough to lend objectivity to such an appeal.

The Clarinet Player , and also his extraordinary wooden still-life constructions (1913-1914), of which nothing seems to have survived except for the very inadequate photographic image. Woman in a Chemise (1915), also known as "Woman with Golden Breasts."

Udnie, an American girl , by Picabia.

To which were subsequently added:

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even , in which the greater part of the cycle of the modern legend flashes forth and is fulfilled for me.

The first "collages" by Max Ernst, arriving from Cologne by post, which one evening, to a few of us, filled us with wonder.

Miró's paintings from 1924-25: The Ploughed Earth , Catalan Landscape (The Hunter) , Carnival of Harlequins , all at once ingenuous, rebellious and so sure of themselves, – mad with joy.

This is what is at the forefront for me, this is what I would like to know the equivalent of for a young eye today.

I have yielded, and would continue to yield, to a need I struggle to explain: the need to "own" paintings. It could be, quite simply, to be able to gaze upon them or change their angle whenever I please, but I believe it is rather in the hope of appropriating certain powers that, in my eyes, they possess. Often, in the evening, I have hung a particular canvas on the wall in front of my bed to test its allure upon waking. In this way, I have been able to ascertain that the happiest vibes were emanating from the blond Braques of 1912. It seems to me that the inquiry I suggested should be extended to this morning questioning, which provides a significant clue to individual taste (in the absence of original works, beautiful color reproductions would allow one to make a judgment, if necessary).

Since, throughout my life, I was far from being able to keep all the paintings I managed to bring into my home, I can quite clearly distinguish between those I wasn't too cruel to part with and those I have constantly regretted, or even find it hard to forgive myself for having had to relinquish to someone else. Among the latter, I will simply mention Melancholy and Mystery of a Street , Woman with a Mandolin , and, above all, Duchamp's Bride

My relationships with paintings, some long-lasting, others fleeting, have left a profound mark on my life. One of my first poems (1916) is dedicated to André Derain, whose pre-World War I work held a long and powerful sway over me. I cherish the memory of the hours spent alone with him in his studio on Rue Bonaparte, where, between two magnificent soliloquies on art and medieval thought, he would read me tarot cards. I rediscovered this connection, immediately captivating, with Vlaminck, to whom, in 1918, I went to ask, on behalf of Apollinaire, about the progress of the sets for The Color of Time . I still remember the brilliance of his fantastical tales, drawn from everyday life, which he himself found terrifying. I can still see myself, one spring morning in 1919, sitting on a bench on the Avenue de l'Observatoire, next to Modigliani, both discovering Isidore Ducasse's "Poésies," which had just appeared in Littérature : no one was quicker to grasp its significance, no one had a more lucid and enthusiastic first impression of this enigmatic work. I recall my frequent visits to the amiable merchant and poet Zborowsky, fearing I wouldn't be able to follow the threads of Soutine's early landscapes, where the most ardent feeling for nature unfolds in sumptuous cashmere. Thinking of my first encounters with him, I am reminded of Braque's profound inner turmoil, a lyre string stretched to the breaking point in the woods. To even consider giving a brief account of it, too many impressions, each stronger than the last, assail me at the mere mention of what Picasso revealed to me of this vein which so often seemed to draw all the blood possible back to the heart. I retain, even more deeply, the regret of not having been able to know, before he began to behave like a vandal on his own land, the prodigious Chirico of 1913-1914, whose lines of light—taken from an unpublished manuscript of his I sometimes meditate on with all the necessary melancholy:

“The Greeks rarely imagined a God in the sky. It was primarily on high places that they saw him. Such is the conception of Greek Olympus: Zeus, with his cerulean gaze, sits atop the highest peak; the expression of his divine torso pushes back the murky depths of the celestial vault; the God is not himself in these depths; he serves only to render them more enigmatic. The same feeling is conveyed, in a more ponderous way, by the biblical legend of Moses who, confined in a pit by Jehovah for fear that the sight of his face would kill the prophet, then sees God's back as he walks away. The principle of revelation lies there. Perhaps with a greater effort of abstraction, by shifting the angle of matter and its meaning , the point of eternity would appear, shining in space like the crystalline tear of a God who had wept with joy.” »

Since I cannot mention here – which would take me too far afield – the artists who, for a quarter of a century, were truly my comrades in arms, I flatter myself that I was the first, in 1933, to welcome Kandinsky's arrival in Paris , that I persuaded him to be the guest of honor of Surrealism at the Surindépendants, and that I anticipated by many years his present consecration by celebrating, while he was still very much alive, his "admirable eye, barely veiled behind the glass, [which] forms with the air a pure crystal, sparkling with all the iridescence of rutile in quartz. This eye – I asserted – is that of one of the very first, one of the greatest revolutionaries of vision. Paris, March 1952. André Breton."